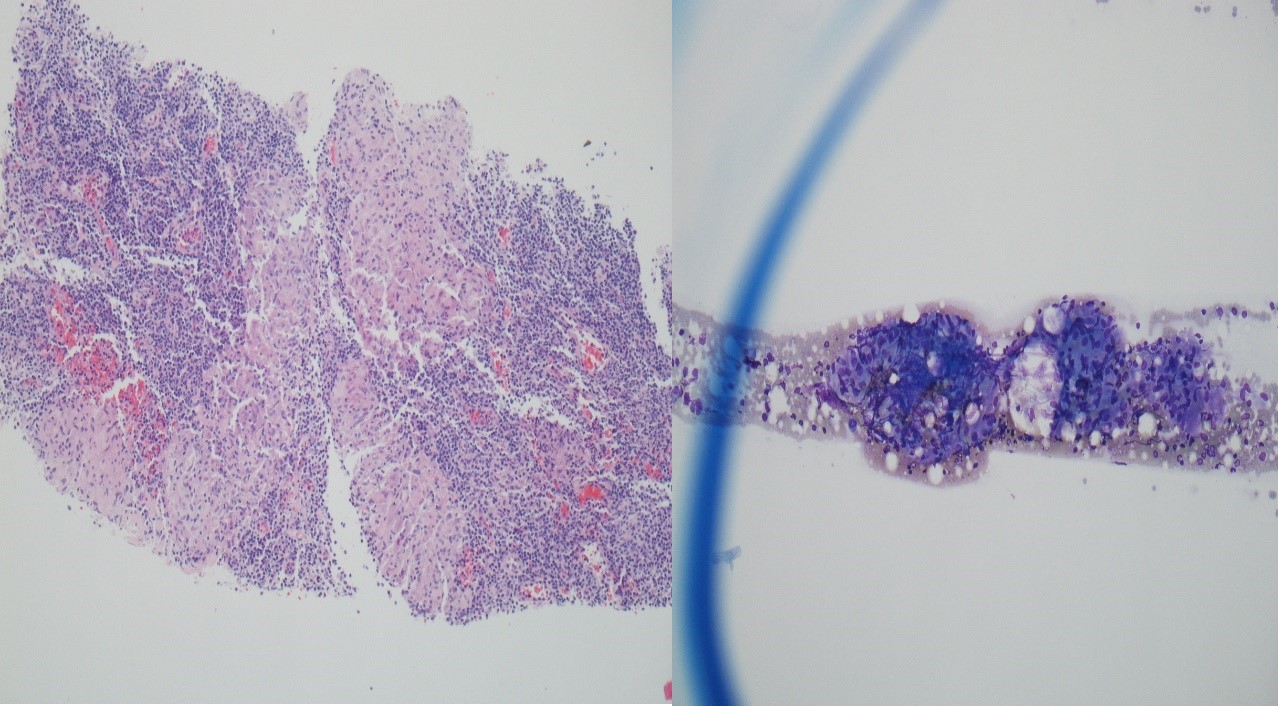

Case Presentation: A thirty-one-year-old man presented to the ED complaining of right-sided facial droop of one-day duration. He also complained of left-sided facial numbness and tingling, right lower extremity shooting pain for one week, night sweats, 50-60 pound weight loss, fatigue for a few months. He denied vision changes, headache, focal weakness elsewhere on his body. He had left-sided facial droop a month ago which fully recovered on prednisone and acyclovir. He was diagnosed with pulmonary embolism two months prior to the presentation but was not on anticoagulation. Vital signs were stable on admission. Physical exam revealed right-sided facial droop, the neurological exam was otherwise unremarkable. CT brain and CT Angiogram brain were normal, CT Angiogram chest revealed multiple chronic or partially treated linear filling defects in pulmonary artery branches supplying right lower lobe with bulky lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly. MRI brain was unremarkable, and MRI lumbar spine revealed degenerative changes at L4-L5 and L5-S1 with disc extrusions and nerve impingement. Labs revealed elevated calcium of 11.3, ACE level normal at 60, SPEP without M component, 25-hydroxy vitamin D reduced to 9.7, CRP elevated to 0.9, ESR elevated to 36, 1,25 dihydroxy vitamin D normal at 41, T-Spot TB test was negative, ANA was negative. His recurrent Bell’s palsy, hypercalcemia, bulky lymphadenopathy was concerning for sarcoidosis. The patient subsequently underwent cervical lymph node biopsy which revealed noncaseating granulomatous inflammation suggestive of sarcoidosis, negative for malignant cells, AFB and GMS stains were negative. He was discharged on rivaroxaban for his pulmonary embolism and a slow prednisone taper.

Discussion: Neurologic complications occur in approximately 5-10% of patients with sarcoidosis. Facial nerve palsy can develop in 25-50% of patients with neurosarcoidosis. The onset of neurosarcoidosis is most often in the fourth or fifth decade of life and neuropathy is rarely the presenting feature of sarcoidosis. Our case was unique since the patient was relatively young and had no other classic symptoms of sarcoidosis. His workup ruled out life-threatening diseases like stroke or malignancy. Infectious etiologies were felt to be less likely with no fever, skin lesions, normal white blood cell count. Although noncaseating granuloma is a non-specific finding which could be seen as a reaction to drugs, infection, tumor antigens, foreign bodies, these etiologies were ruled out in our patient. The constellation of facial nerve palsy, weight loss, bulky lymphadenopathy, elevated inflammatory markers, hypercalcemia, splenomegaly prompted a suspicion for sarcoidosis and a lymph node biopsy confirmed the diagnosis. The association between venous thromboembolism and sarcoidosis has also been reported recently. Swigris et al found PE in 2.5% of US decedents with sarcoidosis, regardless of gender, race or age. The mechanisms responsible for thromboembolism are not clear and may be influenced by several factors including inflammation, compression of pulmonary arteries by enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes or other comorbid conditions predisposing to thromboembolism.

Conclusions: Sarcoidosis should be considered in patients presenting with recurrent Bell’s palsy. Sarcoidosis is often a clinical diagnosis and proper workup should be done to exclude other possibilities. There is also an increased risk of thromboembolism in patients with sarcoidosis.