Background: In the United States, 32 million people have a documented penicillin allergy and up to 20% of hospitalized patients’ records describe a penicillin allergy (PcnA). Less than 10% of patients with reported penicillin allergy have true clinically relevant PcnA when objectively tested through rigorous skin testing (1-3). Clinicians subsequently avoid appropriate penicillin or penicillin related antibiotics even though the patient likely does not have a true PcnA. Patients labeled as PcnA may experience worse outcomes (4). Little evidence is available to understand outcomes in patients with sepsis who also have documented PcnA. This study compares the outcomes of inpatients with sepsis, severe sepsis, and septic shock and labeled as having PcnA compared to those who do not have labeled PcnA.

Methods: We collected retrospective data with institutional IRB approval from 2016 – 2018 for hospitalized patients with diagnosis of sepsis, severe sepsis and septic shock who were labeled as PcnA or non-PcnA. Inclusion criteria were adults diagnosed with sepsis, severe sepsis, or septic shock. Exclusion criteria were age < 18 years old and did not consent to their health data used for research. Statistical tests included calculations of means, medians, proportions, Mann-Whitney, two-sample t-tests, Chi-squared or Fisher’s Exact tests, and linear and logistic regression models and p-values < 0.05 were considered significant.

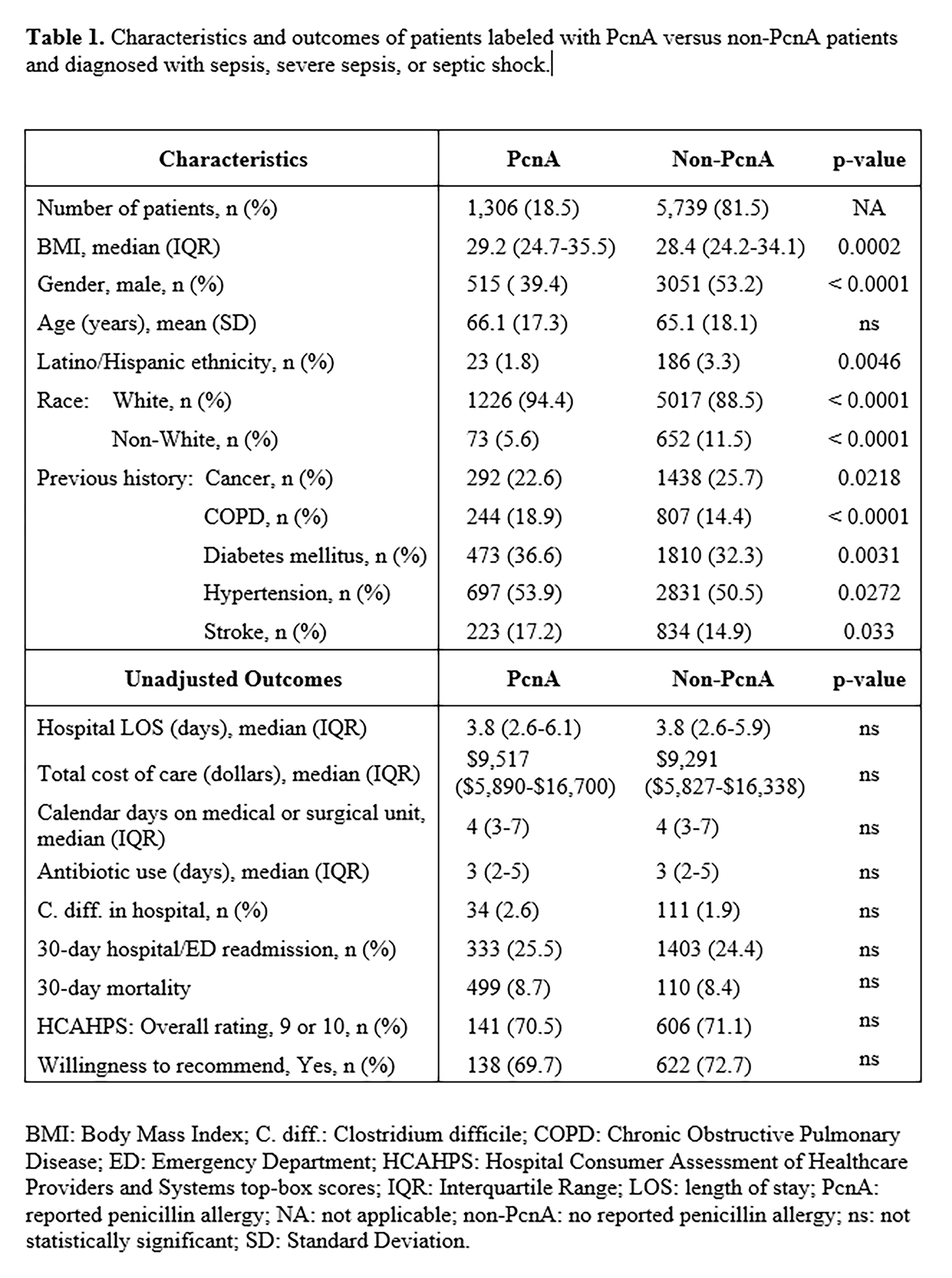

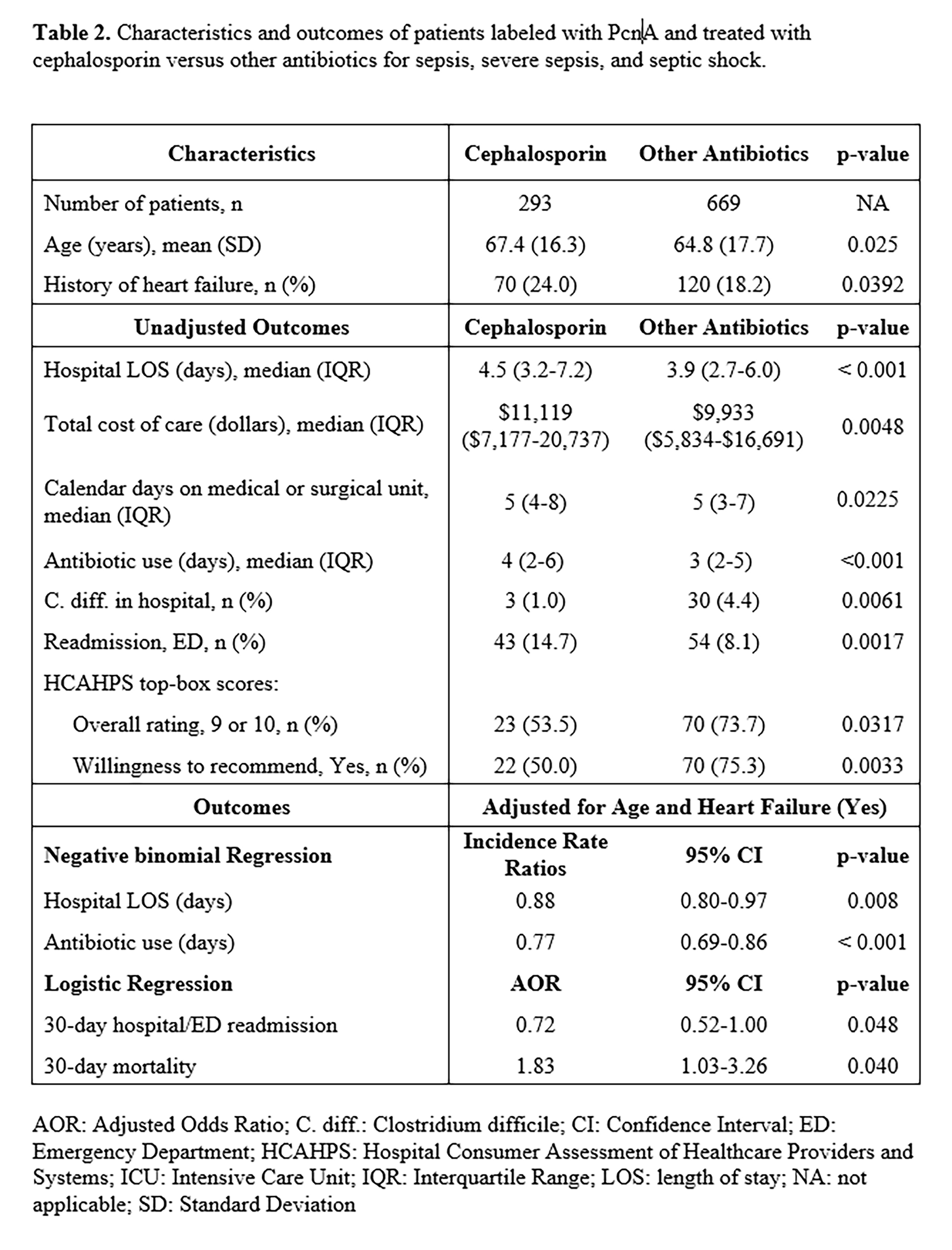

Results: We analyzed retrospective data from 7,045 hospitalized patients of whom 1,306 (18.5%) had a PcnA label and 5,739 (81.5%) did not. There were differences in patients’ characteristics between the PcnA and non-PcnA groups (Table 1). There were no differences in major outcomes between the groups including hospital length of stay (LOS), antibiotic days, and hospital acquired Clostridium difficile infection (Table 1). We performed subgroup analysis of PcnA patients who received cephalosporin or other antibiotics (non-penicillin and non-cephalosporin). Heart failure patients with a PcnA label had a higher rate of cephalosporin use (p = 0.0392). We found that PcnA patients who received cephalosporin had a longer median hospital LOS (p < 0.001), higher total cost of care (p = 0.0048), more days of antibiotic use (p < 0.001), and a higher 30-day Emergency Department (ED) readmissions (p = 0.0017) than patients who received other antibiotics (Table 2). When adjusted for age and heart failure, patients who received other antibiotics had a shorter average hospital LOS (p = 0.008) and days of antibiotics use (p < 0.001), lower odds of 30-day readmission (AOR = 0.72, CI = 0.52-1.00), and higher odds of 30-day mortality (AOR = 1.83, CI 1.03, 3.26). Patients who received other antibiotics (non-penicillin and non-cephalosporin) had a higher proportion of hospital-acquired Clostridium difficile infection.

Conclusions: In our study, we did not find differences in outcomes between PcnA and Non-PcnA patients with sepsis, severe sepsis and septic shock. In subgroup analysis the differences observed in outcomes between PcnA labeled patients who received other antibiotics compared to PcnA labeled patients who received cephalosporin (including shorter median hospital LOS, shorter duration of antibiotics, and lower total cost of care) may have been due to use of fluoroquinolone with a faster transition from IV to oral administration. Despite shorter LOS and duration of antibiotic use, the former group had a significantly higher rate of Clostridium Difficile infection.