Background: Over the last few decades, medicine has seen increasing specialization and a proliferation of roles, trends which can complicate patient care in the hospital setting. Inpatient care teams are comprised of many types of members, and the boundaries between roles can change and at times be ambiguous, e.g., between hospitalist and subspecialist consultants. In addition, hospital care team personnel can change frequently, which further complicates care team roles. Who is in charge can vary under these conditions, and it is unclear how these characteristics of inpatient care teams can impact patients’ understanding of their care. Our two-site study focuses on the following questions:1. How well do inpatients understand care team roles and responsibilities while in the hospital? 2. How often do patients experience miscommunications (mixed messages) in their care, and between which groups of providers do these mixed messages occur?3. What patient characteristics are associated with frequency of perceived mixed messages?

Methods: To examine our main research questions, we designed a survey instrument in REDCap, which was refined through consulting the relevant literature, multiple iterations of cognitive testing with a patient and family advisory council, and pilot testing. We administered surveys in-person or by phone to inpatients at two urban hospitals. We randomly selected patients admitted to general medicine services who were on the third day or more of their hospitalization. A total of 40 patients (n = 14 at Site 1, n = 26 at Site 2) have been surveyed thus far, with the aim of surveying 150 total patients at each site over the next few months. Preliminary unadjusted logistic regression was performed between perceived receipt of mixed messages and patient characteristics (Site 1 only to date).

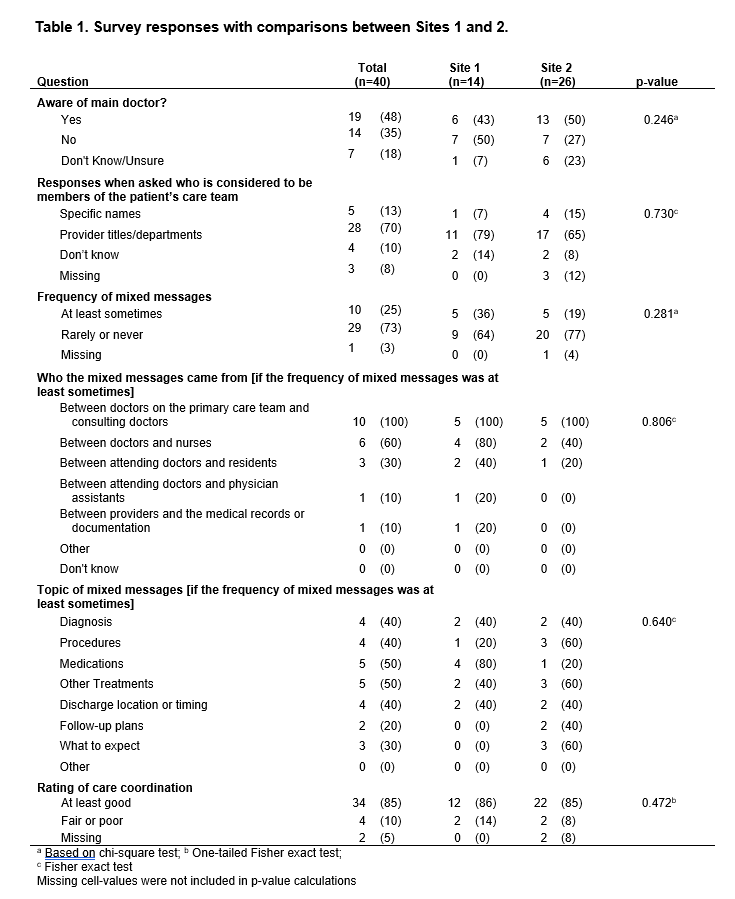

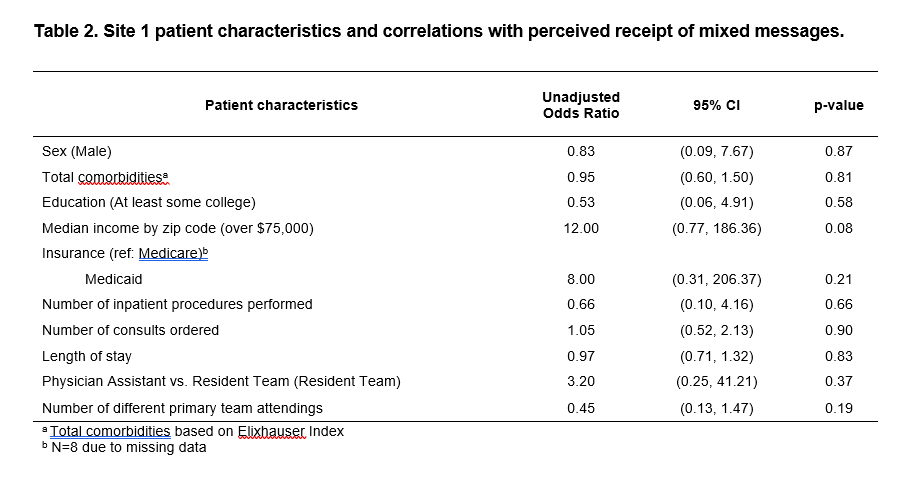

Results: In this initial survey sample of 40 patients, 48% stated that they were aware of who their main doctor was (Table 1). When asked who they considered to be the members of their care team, only 13% of patients responded with specific names, while 70% could name at least the title or department that they belonged to, and 10% did not know. One-quarter of patients responded that they received mixed messages about their care at least sometimes; frequency of mixed messages was higher for Site 1 vs. Site 2 (36% vs 19%). All of these patients experienced mixed messages between primary care team doctors and consulting doctors (100%), and some between doctors and nurses (60%). The topic of the mixed messages most often regarded medications, other treatments, diagnosis, procedures, and discharge location or timing. The two sites experienced similar ratings of care coordination, with an average of 85% of patients rating their care coordination as good or better.At Site 1, having a median income by zip code over $75,000 was associated with perceived receipt of mixed messages, with borderline significance (odds ratio 12.0, 95% CI 0.77-186, p=0.08; Table 2). Small sample size to date precluded multivariable analysis.

Conclusions: The preliminary results of this two-site study shows that a large proportion of patients on inpatient general medicine services are unaware of who their main doctor is and receive mixed messages in their care plan, most often between the primary team and consulting doctors. Clarifying these issues with patients is likely a necessary first step to fully engaging patients in their own care.