Background: Obtaining timely intravenous (IV) access can be challenging for pediatric patients due to physiological and behavioral differences. Many pediatric patients experience multiple needlesticks, leading to trauma and delays in medical interventions. Prior investigators have attempted to implement standardized IV access algorithms, ultrasound-guided IV placement, and stratification of IV placement difficulty using the Difficult Intravenous Access (DIVA) score. Our 110-bed children’s “hospital-within-a-hospital” lacked a standardized tool to predict vascular access difficulty, a protocol for escalation of difficult cases, and proper staff to address these needs.

Purpose: Our purpose was to improve pediatric IV placement practices regarding (1) reduction of attempts needed for successful IV placement and (2) implementation of appropriate comfort measures to reduce discomfort during IV placement. We performed a baseline assessment of pediatric intravenous (IV) access and staffing needed to obtain it. This is part of a children’s hospital-wide quality improvement project that aims to improve IV access practices and reduce the number of sticks required for IV access by forming a multidisciplinary working team, collecting relevant data, implementing a pediatric vascular access guideline and protocol, and a comprehensive improvement plan to reinforce this guideline and protocol.

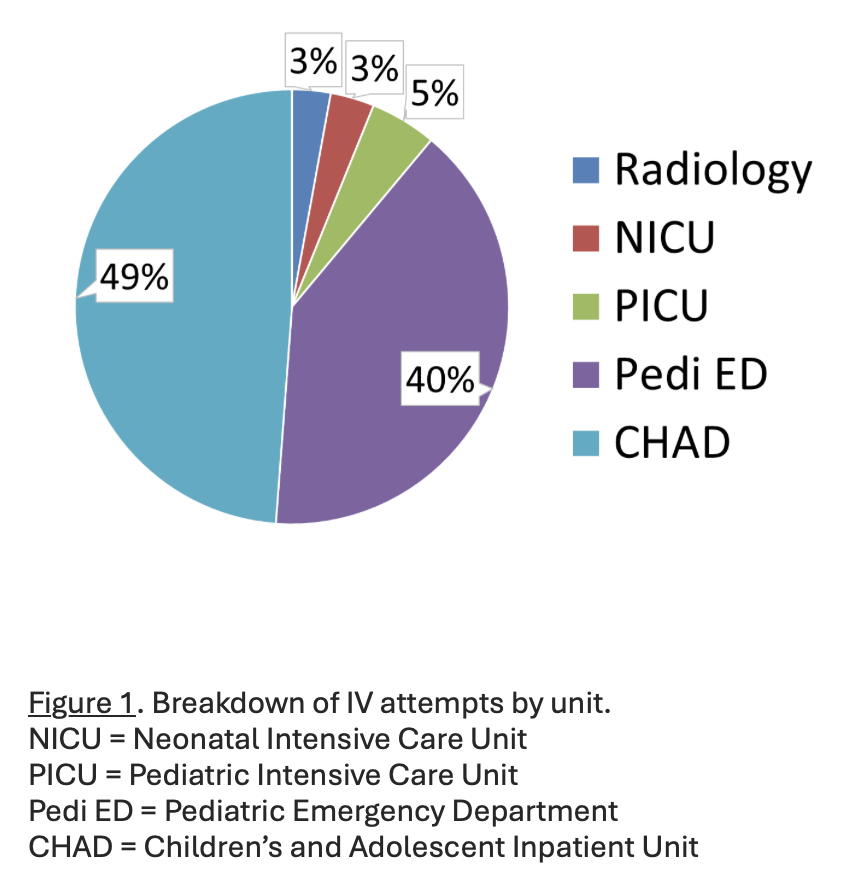

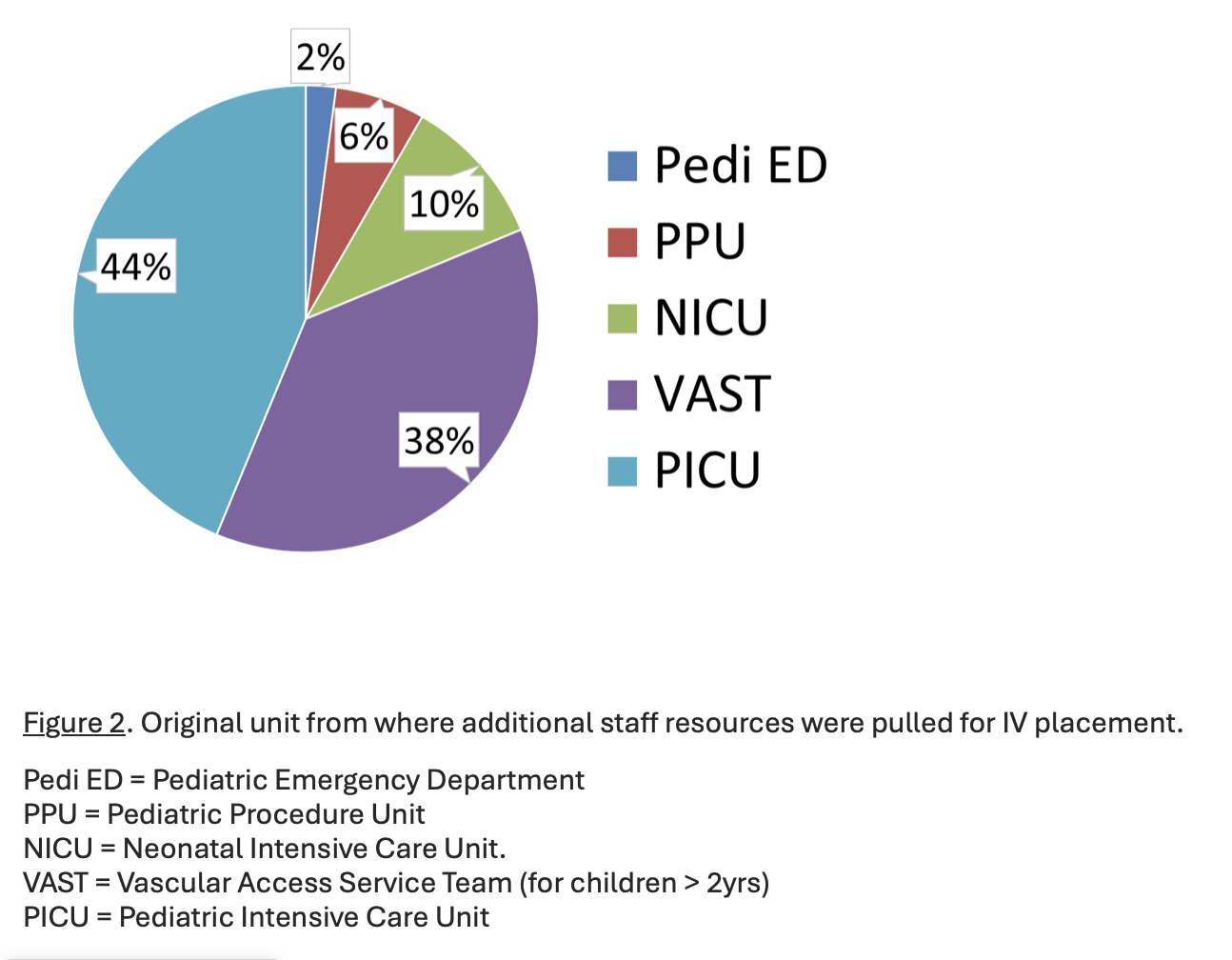

Description: Over two months, baseline data was collected about every IV placed and resources used to obtain it. The study included patients aged 0-22 years who needed IV access anywhere in the children’s hospital. Descriptive statistics were generated, and a Z-test for proportions was conducted to compare the incidence of multiple needlesticks between patients ≤ 2 years and those aged 3-21 years. Training sessions on ultrasound-guided IV placement were provided to nurses and residents across multiple departments. As a quality improvement project, this was deemed non-human subject research by the Human Research Protection Program. Our baseline data showed that 777 patients got 1,010 IVs, which required 1,266 needlesticks, primarily in the inpatient unit and the pediatric ED (Figure 1). Of these patients, 6% required > 4 needlesticks, and 0.5% required > 10. Patients ≤ 2 years needed significantly more needlesticks (average: 2.1) compared to patients aged 3-21 years (average: 1.4), (p < 0.00001). Frequently, staff from other departments, primarily the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit, were required to assist with IV access, leading to precious time away from their assigned units (Figure 2). Thirty nurses and eight residents have completed ultrasound training thus far. A pediatric vascular access guideline and pathway has been developed and implemented based on this data. This guideline was based on multidisciplinary discussions with clinical leaders in multiple locations across the children’s hospital. Future interventions will include recurring educational cycles and potential expansion of the pediatric vascular access service team.

Conclusions: Pediatric patients requiring IV access often face multiple needlesticks, with younger children (≤ 2 years) being especially prone to this trauma. Our descriptive data underscores the need for hospital-wide improvement, including a formalized guideline to escalation pathway for pediatric IV access, incorporating the use of ultrasound in difficult cases and the addition of specialized staff to reduce the strain on our current staffing model.