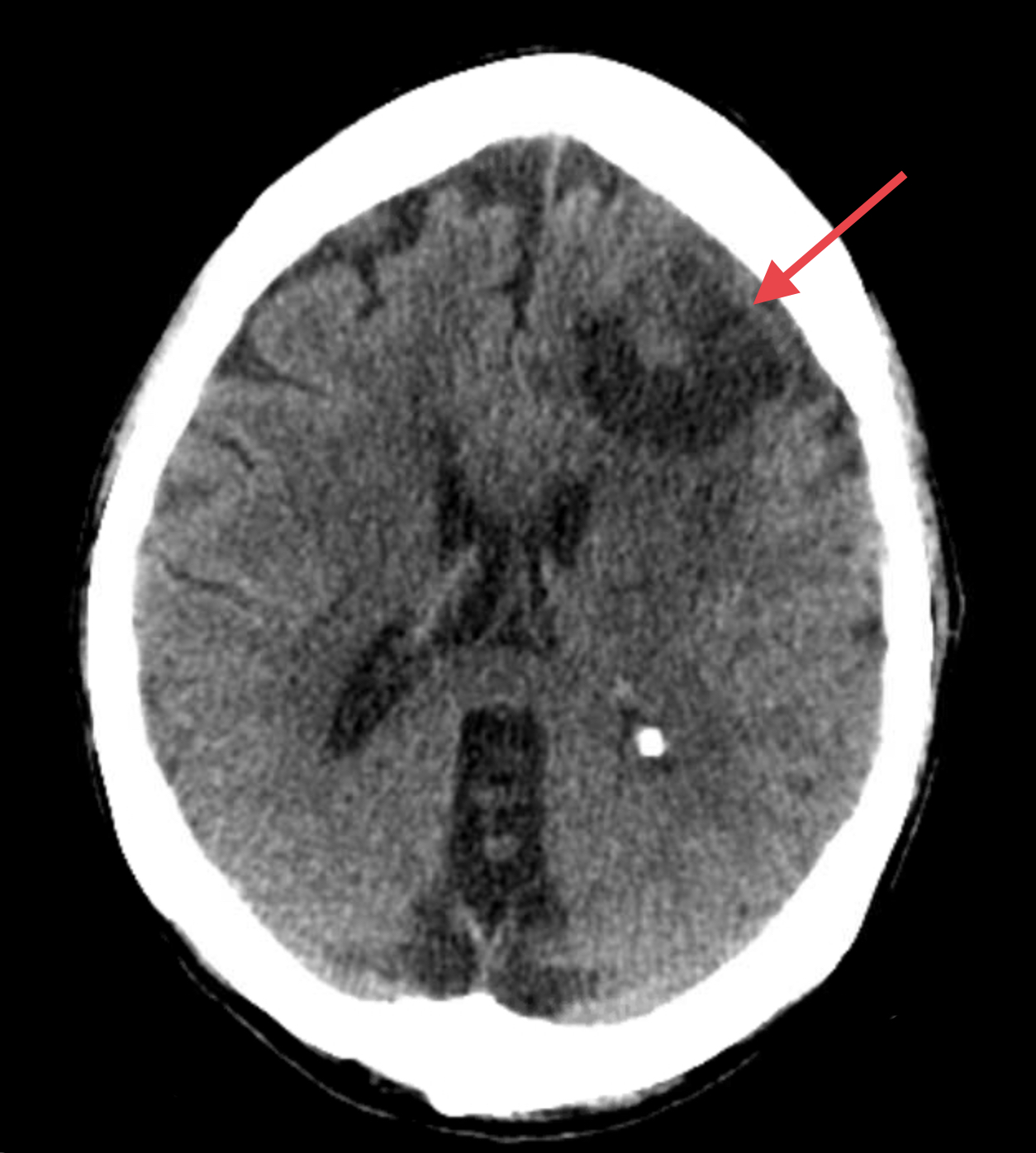

Case Presentation: A 77-year-old female with a history of hypertension and stage IV uterine carcinosarcoma treated with resection, peritoneal debulking, and chemotherapy, presented to the hospital with chest pain and shortness of breath. Her workup revealed new anemia and pulmonary metastatic disease. She underwent an esophagogastroduodenoscopy and colonoscopy for her anemia workup which showed no clear evidence of blood loss. Approximately 4 hours after this procedure, she endorsed a sudden-onset severe headache, different from any headache she had in the past. A stat computed tomography revealed a left frontal lobe hypoattenuating mass with a central isoattenuating lesion suggesting acute hemorrhage with mild mass effect and vasogenic edema. Upon review of her perioperative course, her home antihypertensives, losartan and hctz, were continued given her persistent hypertension during admission, while her home metoprolol was held to avoid masking acute blood loss tachycardia. At the start of the procedure she was noted to have a blood pressure of 202/117 and tachycardia to 127 requiring intravenous antihypertensive management throughout the intraoperative period.

Discussion: This is a case of acute intracranial hemorrhage in a patient with hypertension and newly metastatic pulmonary and brain disease. Since Mangano et al. published findings that perioperative atenolol decreased myocardial ischemia in 1996, multiple investigations have examined perioperative beta-blockers and their associated risks and benefits. Consistent benefits of perioperative beta-blockade include reduced mortality and cardiovascular events during the immediate postoperative period, though an increased risk for vasopressin use and a longer PACU stay. Alternatively, the withdrawal of beta-blockers during this period is associated with high mortality and cardiovascular events. The decision for holding this patient’s home beta-blocker, driven by a concern for active gastrointestinal bleeding, likely led to her peri-intubation severe hypertension and tachycardia, thereby contributing to increased intracranial pressure that led to her acute onset headache and subsequent discovery of an intracranial metastatic lesion. A review of the perioperative beta-blocker literature also reveals its association with perioperative stroke. This correlation has primarily been linked to metoprolol, while other beta blockers like bisoprolol, carvedilol, nadolol, propranolol, and sotalol do not have this association and its mechanism remains unclear.

Conclusions: Medication reconciliation and management is a critical component of perioperative evaluation for the general medicine provider, especially in the inpatient setting. This case of beta-blocker withdrawal shows the potential effects of rebound tachycardia and hypertension during the periprocedural period, even for non-surgical procedures requiring anesthesia. This strong correlation between beta-blocker withdrawal and postoperative mortality and cardiovascular events should be considered when reconciling medications. Often patients have multiple active issues being considered during a perioperative evaluation and providers must review a complex risk and benefit assessment using available literature that best fits their patient. This case highlights how integrating gastrointestinal bleeding, metastatic malignancy, and uncontrolled hypertension complicates a high-risk periprocedural period.