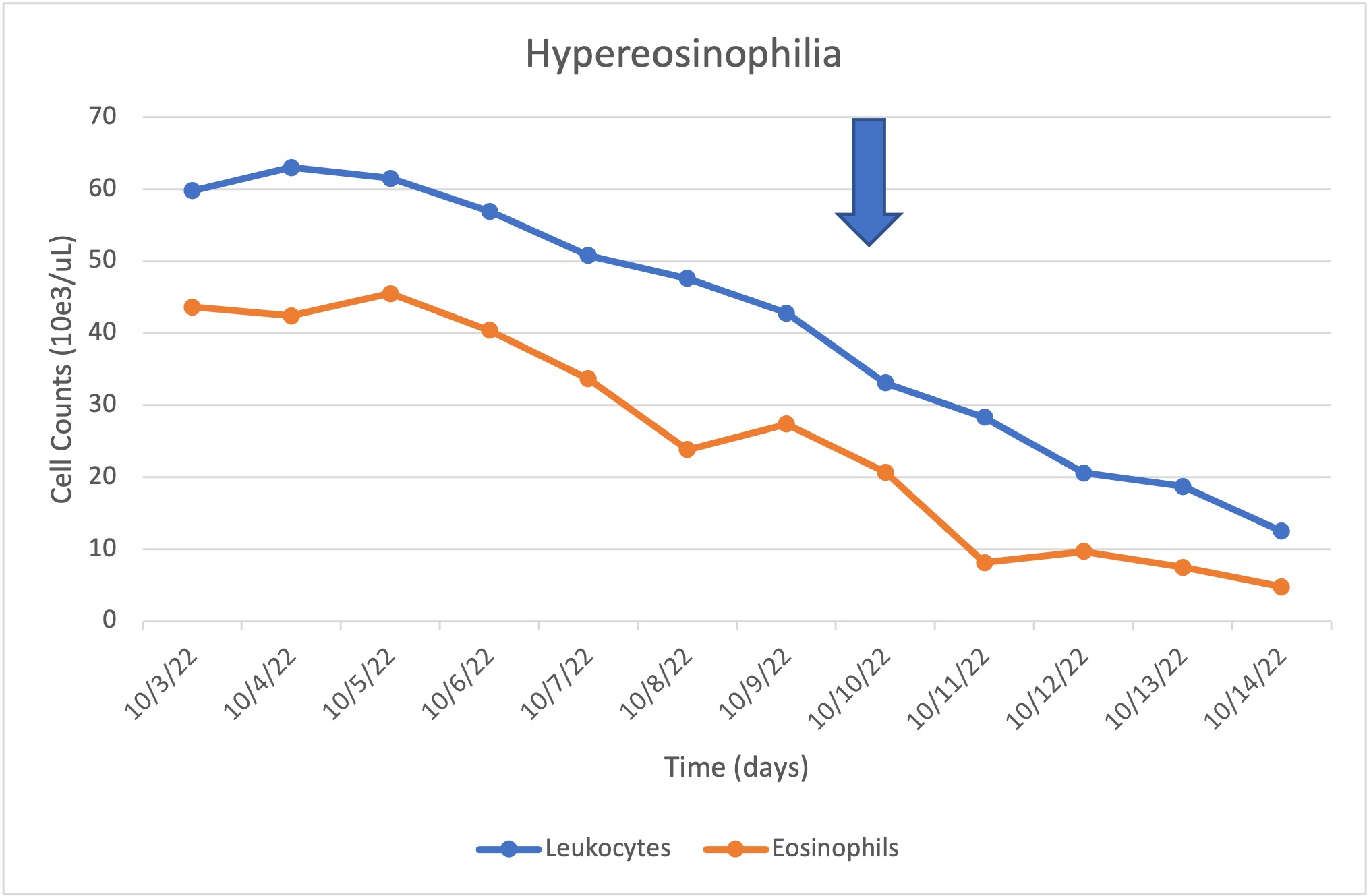

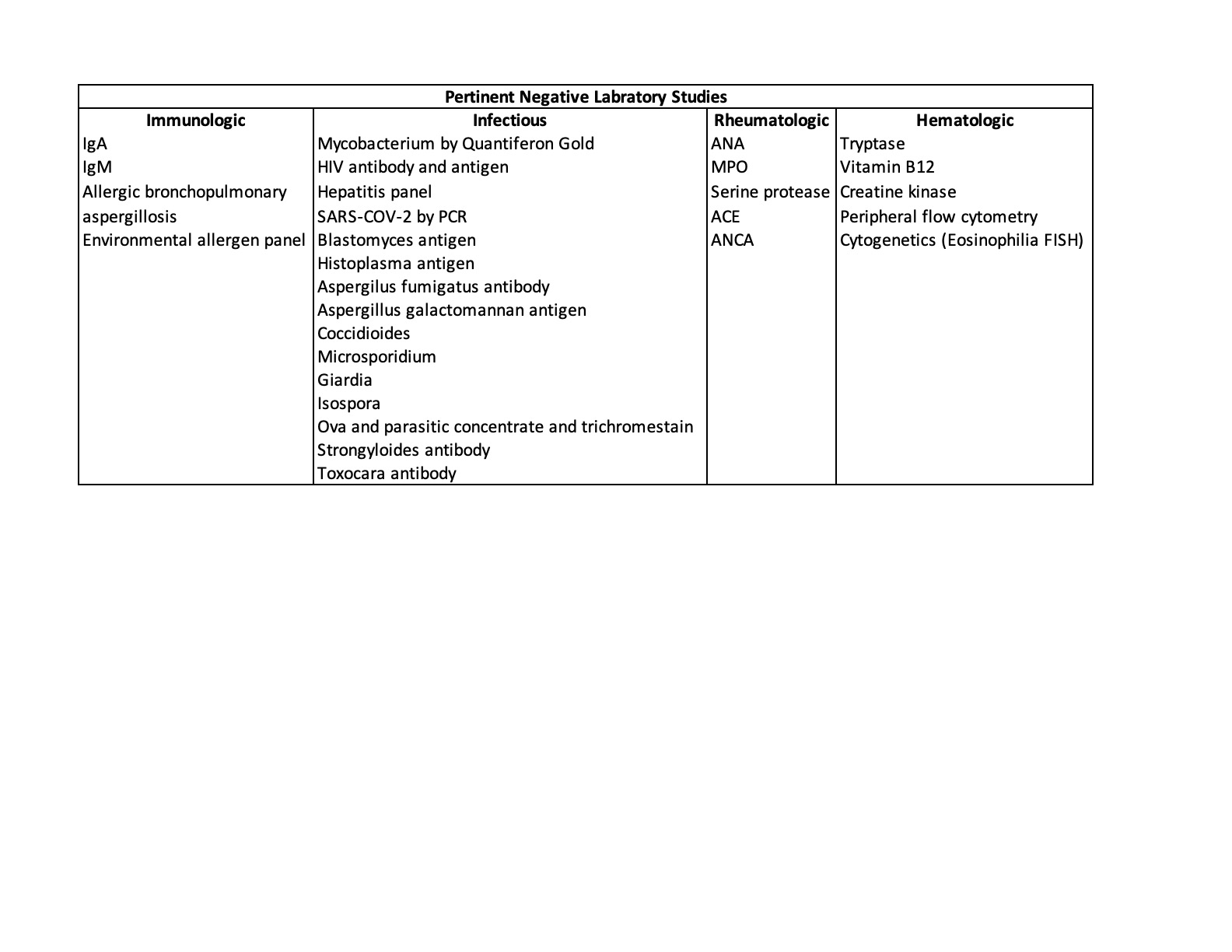

Case Presentation: A 44-year-old African American male with a history of sarcoidosis presented with shortness of breath, dry cough, and headaches for 10 days, previously treated for sinusitis with amoxicillin and clavulanate without improvement. He is an electrician and smokes 3 packs of cigarettes per week. He denied any history of asthma, eczema, or atopy, and denied fevers, chills, and sick contacts. Patient had lived throughout the US without history of recent travel. No animal or hot tub exposure. On presentation, the patient appeared uncomfortable with bilateral expiratory wheezing throughout the entire lung field. Vitals stable with tachycardia (HR 109) and temperature of 99.8 °F. His liver was palpable. He did not have lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, or skin findings. Preliminary blood tests showed elevated ESR of 35 mm/hour and CRP of 477 mg/l, WBC 35,500/µL and marked eosinophilia with an absolute eosinophil count (AEC) of 23,790/µL. Chest X ray was unremarkable. Right upper quadrant ultrasound did not show hepatomegaly nor splenomegaly. CT chest without contrast showed bilateral bronchiectasis with bronchial wall thickening and mucous plugging. Symptom relief was attempted with acetaminophen, ibuprofen and scheduled inhaled bronchodilators. Throughout admission, he continued to have shortness of breath with WBC and AEC peaking at 63,000/µL and 45,510/µL, respectively (Figure 1). Several teams were consulted and an extensive laboratory workup was performed to narrow down the differential and possible etiology. Immunological studies showed elevated IgE (19,771 kU/L [<=214 kU/L]), and IgG (1,885 mg/dL [700-1,600 mg/dL]). All other pertinent laboratory studies were unremarkable (Table 1). In light of the unclear etiology of the patient's persistent hyper-eosinophilia, and largely unremarkably workup, a video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) procedure for lung biopsy was performed, giving a final diagnosis of eosinophilic bronchiolitis with mild respiratory bronchiolitis. Fungus culture grew Aspergillus fumigatus; however, this was likely not an active infection. Patient was treated with Prednisone and anti-IL-5 (such as mepolizumab) and discharged with follow-up.

Discussion: Eosinophilic lung diseases necessitate a broad differential with multiple possible etiologies [1]. Hyper-eosinophilic bronchiolitis is a rare diagnosis often requiring BAL or lung biopsy to distinguish from other causes [2]. Hyper-eosinophilic obliterative bronchiolitis (HOB) is defined by Cordier et al [3] as 1) blood eosinophil cell count >1 G/L and/or BAL eosinophil count >25%; 2) persistent airflow obstruction not improved after prolonged inhaled bronchodilator and corticosteroid therapy; and 3) a lung biopsy with inflammatory bronchiolitis with prominent eosinophil infiltration.

Conclusions: Although similar to asthma in presentation (cough, dyspnea, wheezing), HOB necessitates a distinct treatment regimen to achieve remission, illustrating the importance of identifying HOB as a separate diagnosis earlier in presentation. The pathophysiology of HOB varies, likely idiopathic in this case, however similar biologic processes led to the diagnosis including small airway involvement, prominent eosinophilia, immune dysregulation, and immunosuppressant drug role [4]. Treatment typically involves prolonged course of systemic corticosteroids with a potential role for biologics targeting eosinophilic inflammation [5,6].