Background: In hospitalized patients with anemia, the AABB recommends that transfusion of red blood cells occur when a patient’s hemoglobin (Hb) drops below a restrictive transfusion threshold, either at 7 or 8g/dL1. These transfusion guidelines are the result of a growing body of clinical trial evidence showing that transfusion at lower or restrictive Hb thresholds is safe, compared to transfusion at higher or more liberal Hb levels, using mortality as the primary outcome. These guidelines have become standard of care and been incorporated into practice by hospitalists, but they do not specify how or whether individual patient characteristics beyond Hb level, such as patients’ demographic or clinical characteristics, may influence the need to receive or not receive a transfusion within restrictive transfusion ranges (7-8g/dL). As a result, there may be variation among hospitalists in restrictive transfusion practices based on patients’ individual demographic and clinical characteristics. The purpose of this study was to test for variation in restrictive transfusion practices and determine whether any variation in transfusion practices was associated with patients’ demographic or clinical characteristics.

Methods: Hospitalized general medicine patients were approached for recruitment into the University of Chicago Hospitalist Project (UCHP), a long running clinical research study at UChicago Medicine. Among patients consenting to participate in the UCHP, those with a Hb < 10g/dL were eligible for this study. Patients with sickle cell anemia were not eligible because transfusion practices for this condition are separate from restrictive transfusion practices. Transfusion and Hb data were collected from the hospital’s administrative data mart. Multivariable linear regression was used to test the association between receipt of a transfusion as the dependent variable and patients’ demographic (age, gender, race, ethnicity) and clinical characteristics (Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), length of stay (LOS)) as the independent variables, controlling for patients’ admission and nadir Hb levels.

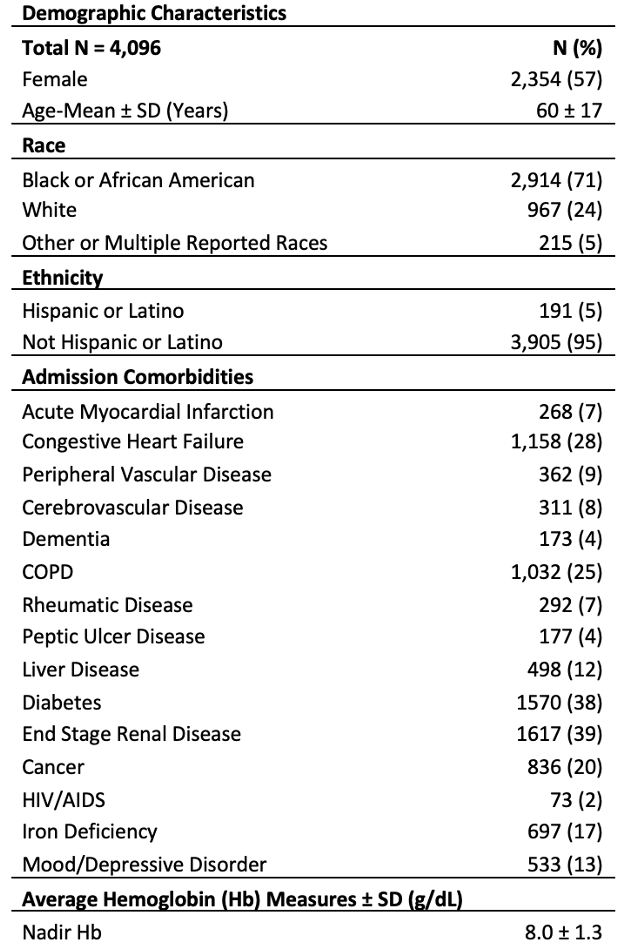

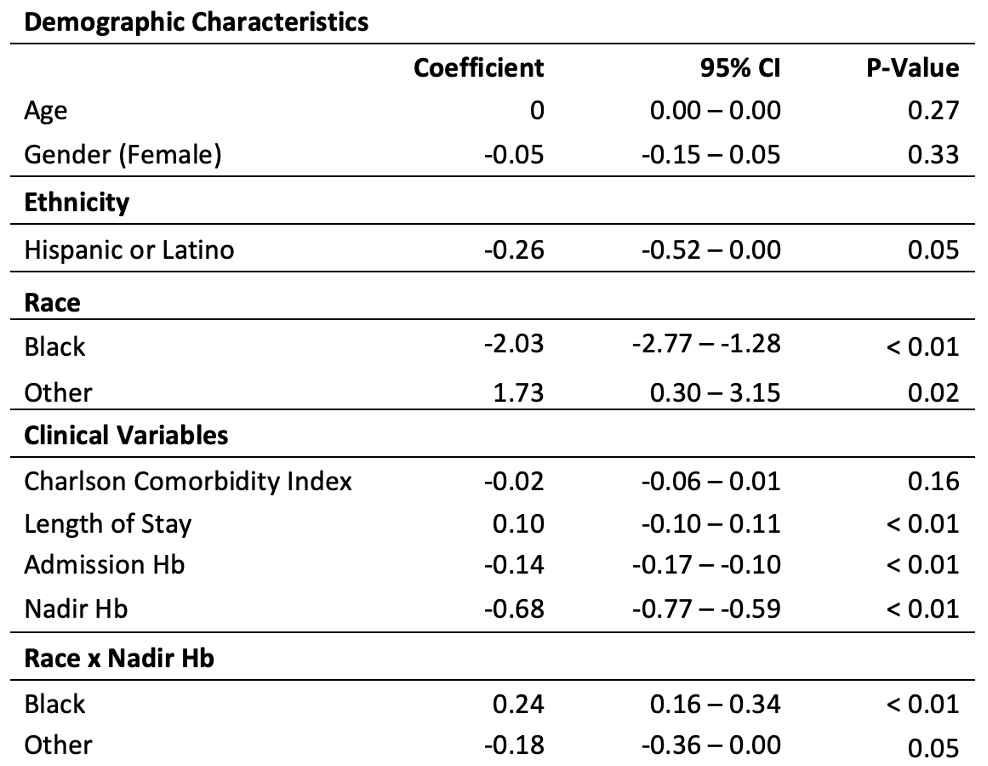

Results: 4,096 patients consented to participate, of which 26% received a transfusion. The average age was 60 (±17), 57% of patients were female, 71% were African American, and 95% were non-Hispanic/Latino (Table 1). The mean nadir Hb was 7.9 g/dL (±1 g/dL). The rate of transfusion was 2% for patients with a nadir Hb of 8-10 g/dL during hospitalization, 21% for patients with a nadir Hb between 7-8 g/dL, and 83% for patients with a nadir Hb < 7g/dL. In the regression model, Hispanic or Latino patients were less likely to receive a transfusion compared to non-Hispanic/Latino patients (β = -0.26, P = 0.05). Compared to white patients, Black patients were less likely to receive a transfusion (β = -2.03, P < 0.01), and patients reporting a race of “other” were more likely to receive a transfusion (β = 1.73, P < 0.01). A longer LOS (β = 0.1, P < 0.01) was also associated with a higher likelihood of receiving a transfusion. There was no association between transfusion and age, gender, or CCI (Table 2).

Conclusions: Transfusion rates were found to differ by race, ethnicity, and LOS. The differences in transfusion by race and ethnicity are surprising findings as they do not have a clear biologic or pathophysiologic explanation. Future work should focus on these differences to determine how and why transfusion practices may vary by patient race and ethnicity and whether these variations reflect underlying disparities in care.