Background: Despite a commitment to high-quality medical education, diagnostic errors continue to be pervasive. Clinical presentations with nonspecific symptoms and diagnoses with wide differentials are prone to diagnostic errors; dizziness may be the epitome of this conundrum. Dizziness is a common symptom, costly to assess, and frequently misdiagnosed. Diagnostic decisions have high stakes, given the risks associated with missed stroke. We hypothesized that novice clinicians could become proficient in diagnostic reasoning related to dizziness with training on virtual patients when compared to their senior colleagues with actual clinical practice.

Methods: Virtual patients (VP) were created on an interactive, screen-based microsimulation software environment. The software simulates a real bedside encounter, leveraging gaming approaches to incentivize a “least-moves” strategy to diagnosis with each item having associated virtual costs. Structured history and videotaped physical exams from an NIH sponsored multi-centered clinical trial of patients with acute dizziness were incorporated into each case simulation for maximal fidelity. We used a prospective, quasi-experimental, pre-test/post-test, nonequivalent comparison group study design. Both intervention (interns in internal medicine) and control groups (senior residents in internal medicine) completed 6 pretest virtual cases. Then, the interns were exposed to 9 hours of curricular material: online content plus practice and teaching with 14 virtual training cases – SIDD (Simulation-based curriculum to Improve Diagnosis of Dizziness). The residents were exposed to online content alone. After 1 week, both groups were assigned 12 posttest virtual cases. Asymmetric intervention groups allowed us to compare SIDD to the cumulative clinical educational experience that trainees are exposed to for dizziness. All virtual cases were different. Our primary outcome was posttest score, reflecting diagnostic accuracy (intervention vs. control). Secondary outcomes were change in accuracy scores, cost assessment of the diagnostic testing ordered. Comparisons were made using Wilcoxon signed-rank tests.

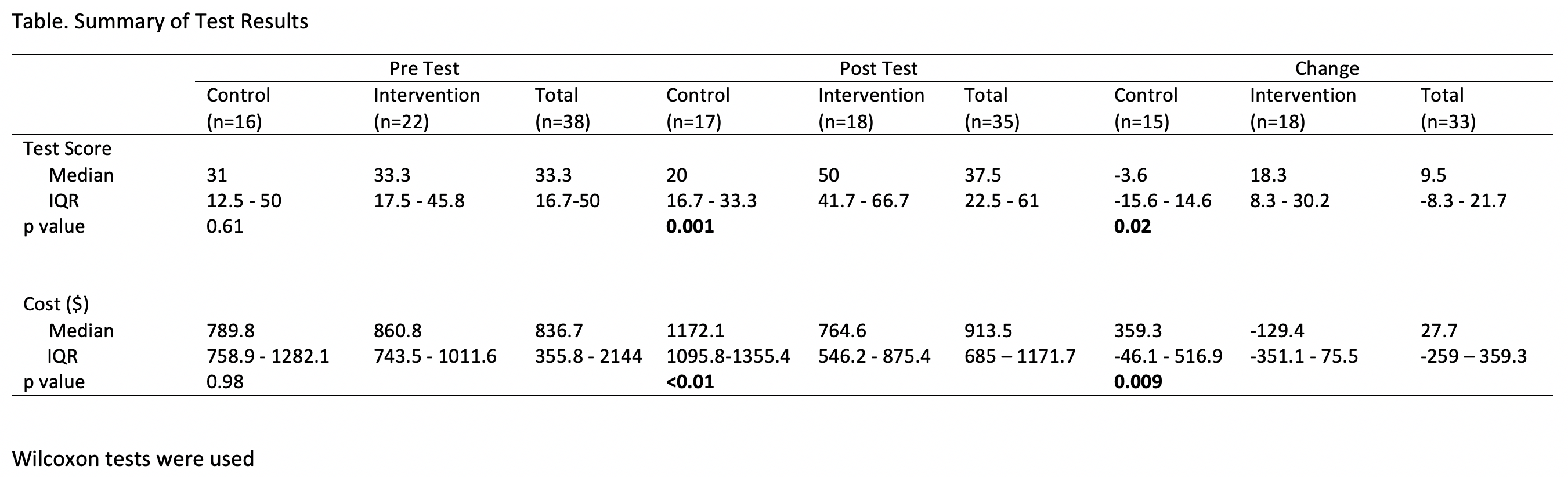

Results: A total of 40 learners (22 interns and 18 residents) volunteered for the study. The Table compares accuracy scores and costs of diagnostic workup for the intervention and control groups during the pre and post-test periods, and also evaluates intra-group changes across the 2 time-periods.

Conclusions: SIDD (with <10 hours of deliberate practice using real-world VPs) was able to significantly improve the diagnostic approach of novice clinicians (interns) such that they were more accurate and chose tests more wisely than their senior colleagues (residents) in their approach to dizziness.Conventional diagnostic teaching around complex presentations, like dizziness, do not work well. Exposing learners to multiple cases concurrently with specific diagnostic features and clues allows for comparisons of similarities and differences that facilitate an appreciation of the subtleties of diagnostic reasoning. Future plans are to apply this condensed educational experience across a broad range of common symptoms that are costly and associated with high rates of misdiagnosis. Applying condensed educational experiences, like this, may translate into value - improved care, reduced costs, and fewer diagnostic errors.