Background: Fingerstick blood glucose (FSBG) testing allows inpatient providers to adjust insulin in real time to protect patients from significant hypo- or hyperglycemia. Admitted diabetic patients are often placed on sliding scale insulin with four times per day FSBG testing, regardless of home insulin use. FSBG test materials cost $9 per use (1). We estimate that over $500,000 is spent annually on FSBG supplies for the hospital medicine teaching service (HMTS).In patients who are low risk for inadequate glycemic control, FSBG monitoring may add to nursing workload, cause patient discomfort, and waste resources without improving quality of care. We performed a study to better define the issue, and assess opportunity to reduce FSBG testing in patients with well-controlled type 2 diabetes.

Methods: Our student-run team conducted a multi-faceted needs assessment of the HMTS at an urban academic 1,100-bed tertiary care center, including a point prevalence study of hospitalized patients, a provider awareness study, and a nurse perceptions survey.The point prevalence study assessed the number of patients on the HMTS receiving FSBG monitoring, defined as an order for four times per day FSBG tests for any patient, regardless of diabetes history. Patients with active FSBG orders were identified through the EMR. The cross-sectional survey of interns, residents, and hospitalist attendings assessed awareness of FSBG orders, similar to Saint et al’s Foley catheter study (2). Each provider was given a copy of his/her patient list and was asked to identify patients prescribed FSBG in the last 24 hours, without looking at the EMR. Participants were observed to ensure that the EMR was not accessed.The nurse perceptions survey was a multiple-choice five question survey assessing common practice and perceived workload attributed to FSBG testing.

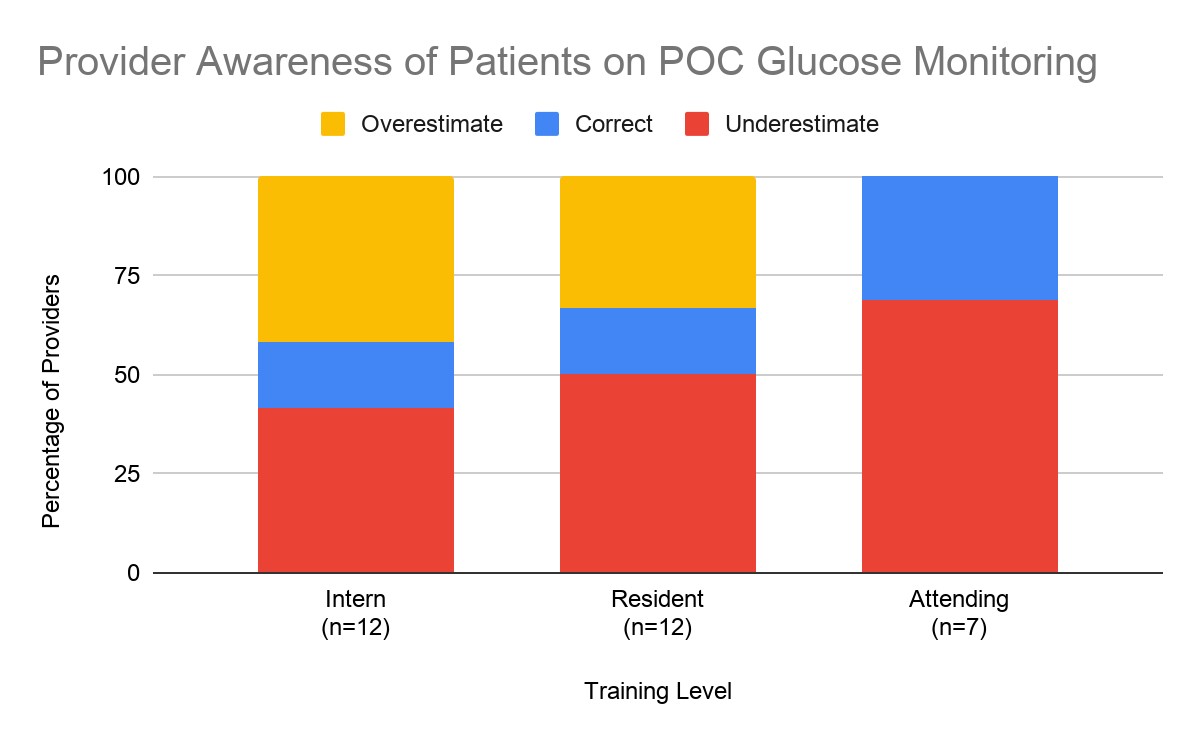

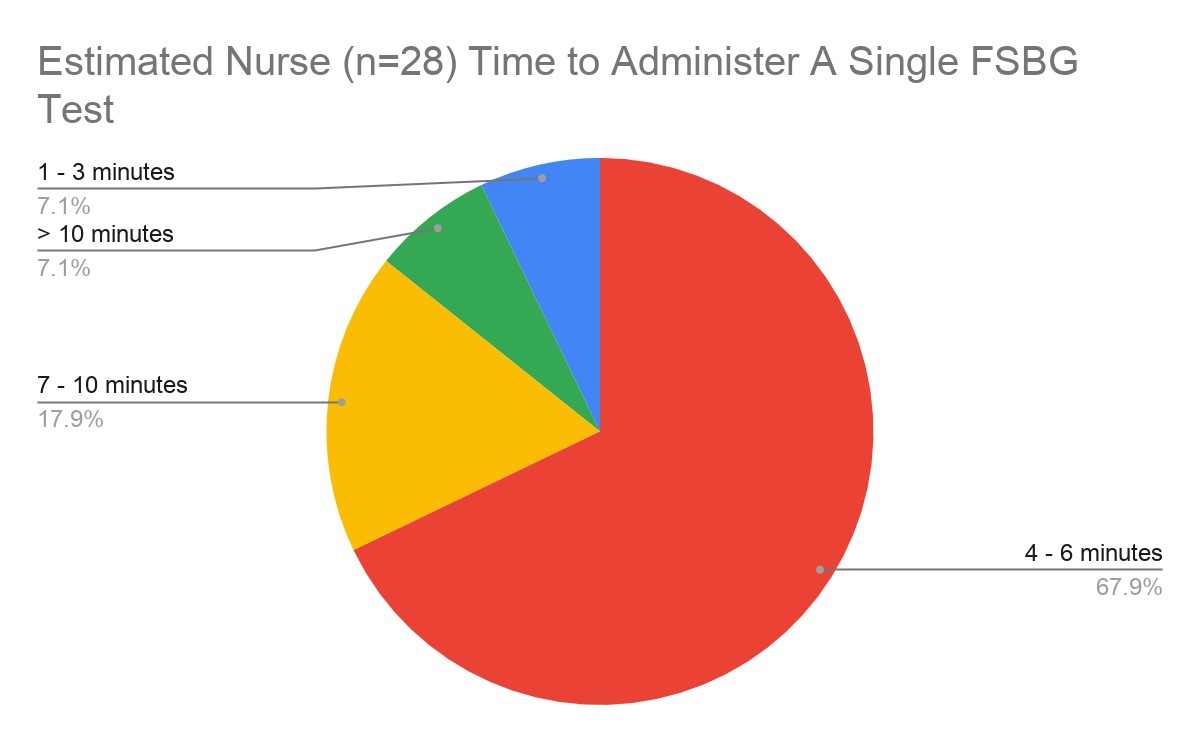

Results: 55 of 103 total patients were receiving FSBG during the point prevalence study. The cross-sectional awareness survey was administered to 31 respondents (12 interns, 12 residents, 7 hospitalists). Only 10% (3/31) correctly identified all patients who had FSBG orders. By training level, 8% (1/12) of interns, 8% (1/12) of residents, and 14% (1/7) of attendings correctly identified all patients on FSBG. Among interns, 42% overestimated and 42% underestimated the percentage of patients on FSBG. Among residents, 33% overestimated and 50% underestimated the percentage of patients on FSBG. 70% of attendings underestimated the percentage of patients on FSBG (Figure 1). The mean percentage of patients receiving FSBG testing who were correctly identified was 66%.The nurse perception survey was administered to 28 nurses with 100% completion. 67.9% reported that it takes 4- 6-minutes to administer a FSBG test, and 17.9% reported it takes 7-10 minutes (Figure 2). 60.7% reported that fewer than 50% of patients getting FSBG testing are given insulin in response to test results.

Conclusions: Our student-run study demonstrates that FSBG testing is common, that provider awareness of FSBG monitoring is low, and that nurses require 4-10 minutes per fingerstick. In aggregate, FSBG is costly. Residents and attendings were more likely to underestimate the number of patients on FSBG, perhaps because such tasks are often delegated to junior team members. As such, FSBG testing represents a potential quality gap. Our work will inform quality improvement interventions to decrease fingersticks that are not changing care, maximize providers’ time and hospital resources and improve patient experience.