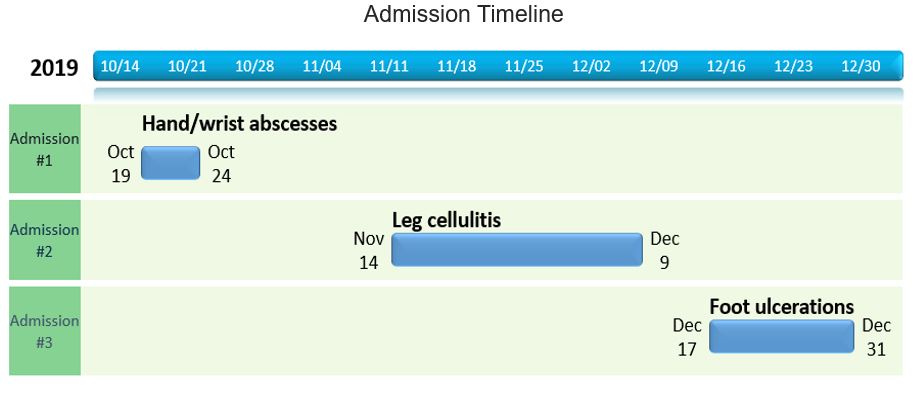

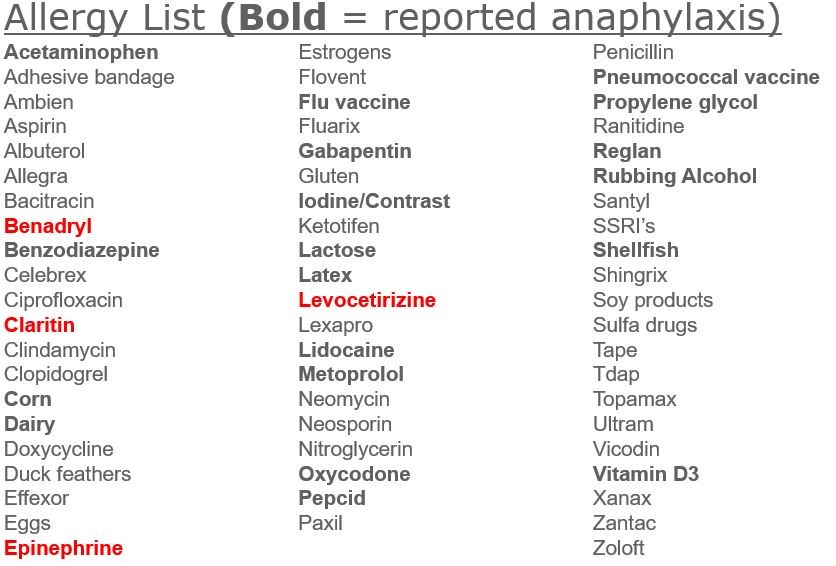

Case Presentation: A 58-year-old woman with self-reported history of mast cell activation syndrome and chronic back pain presented to the hospital three times over a two-month period for recurrent skin/soft tissue infections. Her first hospitalization (10/19 – 10/24) was for bilateral hand/wrist abscesses requiring extensive tenosynovectomy and radiocarpal arthrotomy; cultures grew MSSA and she was treated with 4 weeks of IV vancomycin. Her second hospitalization (11/14 – 12/9) was for bilateral leg cellulitis with weeping edema, treated with IV cefazolin. Her third hospitalization (12/17 – 12/31) was for bilateral purulent ulcerations of the dorsa of the feet, treated with IV vancomycin. Her chronic medications included methylprednisolone and chlorpheniramine prescribed by her family doctor for mast cell disorder. She reported prior anaphylactic reactions to a long list of medications and foods. During her hospitalizations, she was never witnessed to have anaphylaxis, and episodes that the patient described as “mast cell attacks” were clinically consistent with panic attacks. Due to the belief that she was allergic to inactive ingredients of medications, she frequently refused hospital formulary medications and insisted on having all oral medications compounded. Due to perceived food allergies, her diet consisted entirely of carrots, buckwheat cereal, and lamb. Extensive work-up, including multiple tryptase levels and a bone marrow biopsy, showed no evidence of abnormal mast cell activity. Imaging revealed osteoporosis and multiple lumbar compression fractures. Her Vitamin C level was found to be severely low at 0.1 mg/dL, confirming the diagnosis of scurvy.A multi-disciplinary team, including hospital medicine, nursing, infectious disease, psychiatry, and bioethics were involved in this patient’s care. The team conveyed consistent messaging that she did not have mast cell hyperactivity, and that the treatments for it were causing her significant harm. Importantly, these messages were accompanied by compassion and reassurance that we would continue to attend to her symptoms and work to help her feel better. Over time she made drastic improvements in her willingness to expand her dietary choices and to accept formulary medications, including Vitamin C supplements. As an outpatient she is slowly being tapered off her chronic steroids.

Discussion: Caring for this patient provided opportunities to learn about both Mast Cell disease and Scurvy. However, perhaps the most interesting aspect of this case was the devastating impact of the patient’s fixed false belief that she had a disease she did not have. These firm beliefs led her to adopt a severely restrictive diet and to take chronic steroids—ultimately resulting in multiple complications including osteoporosis with compression fractures, recurrent infections, and a critical vitamin deficiency. Though this case was an extreme, all physicians during their careers are likely to encounter patients whose beliefs about health pose a challenge in providing the standard of care.

Conclusions: This case illustrates the importance of seeking objective confirmation of self-reported diagnoses, particularly those whose treatments have the potential for significant harm. When patients do hold false beliefs about disease states, relationship-building and consistent messaging are key to motivating behavioral change.