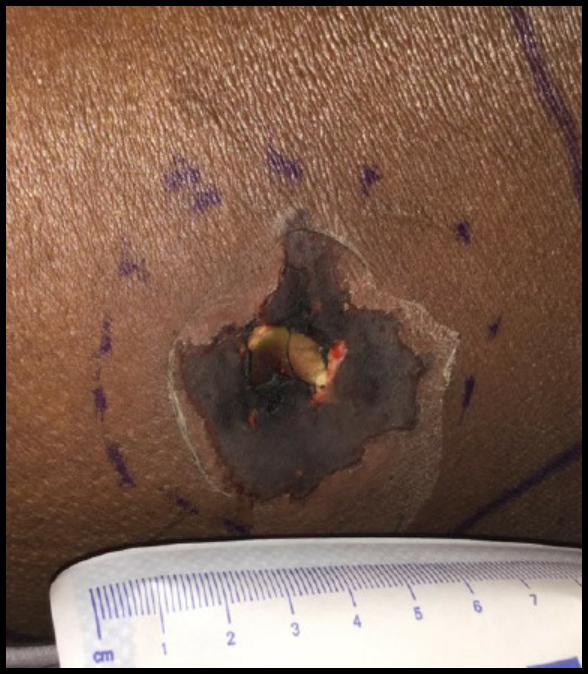

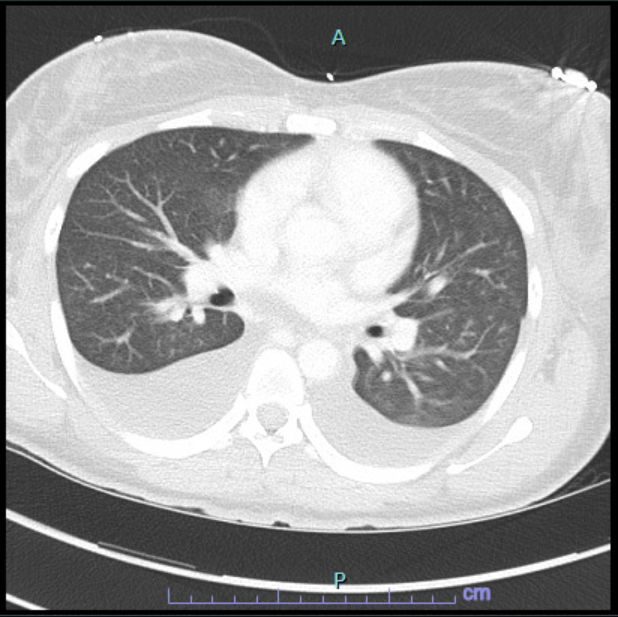

Case Presentation: Few spider bites are medically significant. A 24-year-old African American woman presented with malaise, fever, nausea, and myalgias. She reported a sharp pain on her lower back the night prior that at first felt like burning before progressing to pain. Her initial vitals were T 101, HR 120, BP 141/117. Physical exam revealed a 6x8cm edematous area on her left lower back with erythema and central small vesicle concerning for Brown recluse spider (BRS) bite, and she was admitted on broad spectrum antibiotics. On day 3, she developed a diffuse vasculitic rash and ultimately went into shock with fevers, tachycardia, and significant hypotension requiring transfer to the ICU. Of note, her labs showed a hemoglobin decline from 15 to 11 gm/dL over 3 days. Shortly afterward, she worsened clinically which was represented by a subsequent acute hemoglobin decline from 11.0 to 6.6 gm/dL over a period of 30 hours. There were schistocytes on peripheral smear, undetectable haptoglobin, peak LDH 1415 U/L, and indirect hyperbilirubinemia 6.9 mg/dL concerning for hemolysis. CT chest noted moderate pleural effusions and transthoracic ECHO showed normal systolic function but moderate pericardial effusion. While in the ICU, she developed respiratory distress requiring BIPAP, gross hematuria, an enlarging dermonecrotic lesion over the site of her bite, and generalized desquamation. Given no infectious cause identified, it was thought likely distributive shock in the setting of recent BRS bite. She received blood transfusions and supportive care with stabilization and was eventually transferred to the general floor and discharged. Follow up showed complete resolution of anemia.

Discussion: Loxoscelism is a term used to describe the systemic manifestations from envenomation by the BRS. The venom has potent cytotoxic action facilitated by Sphingomyelinase D (SMaseD) that often leads to dermonecrosis. SMaseD activates complement, induces neutrophil chemotaxis and apoptosis of keratinocytes, and initiates the generation of potent collagen and elastin-degrading metalloproteinases. In rare cases the venom can cause intravascular hemolysis, DIC, and rhabdomyolysis. Diagnosis is clinical, making further evaluation for sequela vital to preventing complications. Patient’s with systemic findings warrant a CBC, CMP, PT/PTT/INR, LDH, haptoglobin, Type and Screen with Coombs, fibrinogen, D dimer, CPK, and UA. Treatment is mostly supportive with replacement of blood products as needed, local wound care, and pain control. Therapies without evidence of efficacy include dapsone, glucocorticoids, and hyperbaric oxygen.

Conclusions: The misdiagnosis of envenomation from Loxosceles reclusa and the consequences of misguided therapies can be catastrophic. The BRS is endemic in multiple states of the Midwest and south-central U.S. A high degree of clinical suspicion is needed to make the diagnosis of systemic loxoscelism (incidence <1%); thus, clinicians should realize the importance of early recognition and appropriate management.