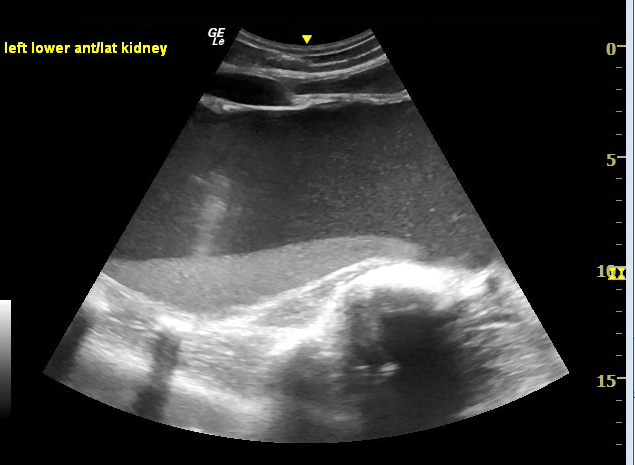

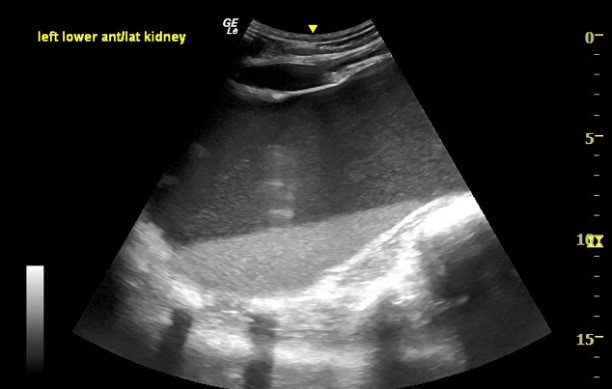

Case Presentation: 30-year-old male with no previous medical history presented with acute abdominal pain of 3 days duration. He noted abdominal distention for several years that was more prominent secondary to recent intentional weight loss. He denied periorbital edema, leg edema, dyspnea, orthopnea or PND. Examination revealed a protuberant abdomen with dull percussion note in the central abdomen and tenderness on left flank. His WBC count was 12 x10 3, , Hb 12.1 g/dL, Platelet 350 x 10 9. Serum albumin was 2.9g/dl with otherwise normal liver function tests, urea and electrolytes. Urine microscopy was bland with no sediments. A point-of-care ultrasound revealed anechoic fluid extending from the left upper quadrant to the mid-abdomen and extending into the left pelvis with isoechoic sediment (fig ). The hepatorenal recess did not show fluid and the left splenorenal recess could not be clearly appreciated. An initial diagnosis of complicated ascites was made, and ultrasound-guided paracentesis was performed from the infra-umbilical approach after identifying the bladder. One hundred ml mucopurulent aspirate was sent for analysis. A CT abdomen and pelvis was then performed showing left hydronephrosis 20 x 15cm, with hyperdense focus in the renal pelvis suggestive of calculus and a normal right kidney 11x 8cm. Patient was started initially on IV cefepime and metronidazole for a presumed complicated intra-abdominal collection. Fluid analysis from the initial aspiration identified WBC count of 2000 cells/mm3 with 85% neutrophils, RBC 50 cells/mm3, that later grew Escherichia coli. The fluid creatinine was 40 mg/dl suggestive of urinary source, with negative cytology exam. The patient completed 14 days of IV antibiotics for infected hydronephrosis. Subsequently, the patient underwent left nephrectomy due to mass effect. A renogram was not performed given the massive hydronephrosis with no discernible architecture. Surgical biopsy later confirmed severe chronic hydronephrosis secondary to ureteropelvic junction obstruction. Patient was safely discharged home after a full recovery.

Discussion: Bedside ultrasound has a sensitivity of 75- 80% for diagnosing unilateral hydronephrosis when compared to computed tomography. Severe hydronephrosis is described when the anechoic region of dilated calyces start to distort the cortex. In our patient the renal parenchyma lacked a discernible architecture appearing as a large collection of fluid inside the abdominal cavity. This led to the initial decision to perform a diagnostic aspiration. The presence of sedimentary echoes inside the bladder or complicated cysts on ultrasonography has been described in the literature previously. However, its presence in a severely hydronephrotic kidney has not commonly been described in an adult population. The presence of sediment inside a large abdominal fluid should prompt the POCUS user to differentiate ascites from complicated renal fluid collection such as infected hydronephrosis or a complicated cyst via advanced imaging modalities to avoid potentially harmful interventions.

Conclusions: The appearance of sediment in an intra-abdominal fluid collection should prompt a POCUS user to proceed with a more advanced imaging modality prior to diagnostic aspiration. Severe hydronephrosis secondary to UPJ obstruction can rarely manifest as large intra-abdominal collection in adults and may be misdiagnosed as ascites on point-of-care ultrasound.