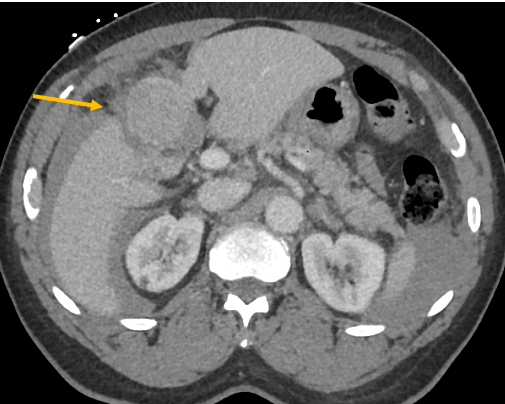

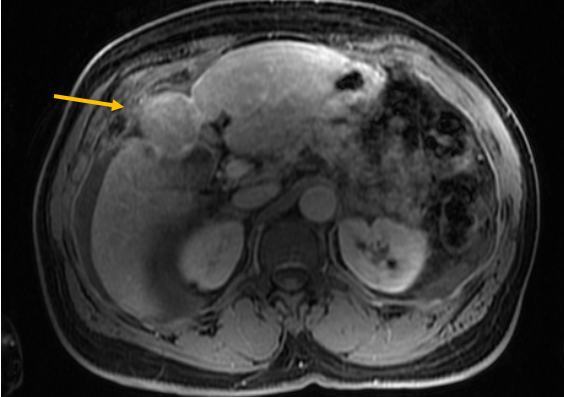

Case Presentation: A 75-year-old male with atrial fibrillation on apixaban and eradicated HCV presented to the Emergency Department one day after a syncopal episode with right upper quadrant abdominal pain. On initial presentation, he was hemodynamically unstable with hypotension and atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response. His vital signs normalized after 2 liters of intravenous fluid. Hemoglobin was 14 g/dL. Comprehensive metabolic panel was unremarkable. Coagulation panel and lactate were normal. A CT chest, abdomen, and pelvis with contrast was significant for heterogeneously enhancing liver mass and a moderate volume of ascites. There were no CT findings of active arterial bleeding. He was admitted to Internal Medicine for further management. Upon admission, abdominal pain improved and hemodynamics remained stable. He obtained a CT abdomen and pelvis with angiography which showed a large pedunculated hepatic mass measuring up to 4.5 cm with capsular disruption and moderate volume hemoperitoneum. Findings were suspicious for a hemorrhagic mass of hepatic origin without evidence of cirrhosis. Repeat hemoglobin was 10.0 g/dL Anticoagulation was held given risk of recurrent hemorrhage. General Surgery and Gastroenterology were consulted. CEA, CA 19-9 and AFP were within normal limits. HCV antibody was reactive, but HCV RNA was negative, consistent with prior eradication. His HBV surface antigen was negative with a positive core antibody. General surgery performed a laparoscopic liver segmentectomy and cholecystectomy without complication. Pathology of the hepatic mass returned with differentiated HCC with negative margins and he was discharged for further outpatient care.

Discussion: Spontaneous rupture of HCC is an uncommon but life-threatening complication. While it is the third most common cause of HCC associated death worldwide, it only occurs in 3% of HCC cases. This is likely due to detection and treatment in people undergoing screening1,2. The diagnosis can be challenging in the absence of known cirrhosis or HCC with presenting signs of abdominal pain and shock. Treatment options for HCC rupture include trans-arterial embolization and resection. Intervention is preferred as lack of intervention carries a 30-day mortality rate up to 90%. Our patient presented without evidence of chronic liver dysfunction and the mass was amendable to surgical resection, offering improved survival and potential for cure. For HCC, the five-year survival is less than 5% except in patients where early disease is detected2. Ideally, screening would focus on accurately detecting HCC at an early stage. However, in most cases, HCC is caught at a later stage either due to ineligibility or non-participation in screening.3 When identified in early stages, HCC can be amenable to curative therapy such as liver transplant, resection or ablation. In these causes, the 5 year survival is greater than 50%4. If HCC is initially diagnosed at the onset symptoms, survival rates are very low.3 Therefore, it’s imperative to continue to improve surveillance strategies to improve overall survival rates. Still, our patient, based on current guidelines, would not have met criteria for screening in the absence of cirrhosis or HBV.5,6

Conclusions: Our case highlights the importance of maintaining a high suspicion for intraperitoneal bleeding in patients presenting with abdominal pain and hypotension and including spontaneous tumor rupture on the differential when a mass and ascites is identified to enable prompt treatment.