Background: Increasing attention has been paid to diagnostic patient safety vulnerabilities, which account for 6 to 17% of hospital adverse events. In 2015, the National Academies of Medicine published a report on diagnostic safety errors, including their causes and evidence to-date on how to intervene to reduce the harm associated with them. In this report, an expert panel created a list of recommendations that included calls to develop more robust methods to identify and learn from diagnostic errors and near misses in clinical practice.

Purpose: A key aspect of improving diagnostic safety at the organizational level is to identify and learn from diagnostic patient safety vulnerabilities. However, few organizations have effective processes to capitalize on these learning opportunities. We sought to develop ongoing processes within our healthcare organizations to identify opportunities for improvement, study them and feed the lessons learned back to individual and the system. We describe the implementation of two separate programs and their initial results.

Description: Triggered case review programs were created at two organizations, Site 1 (Regions Hospital, HealthPartners, Saint Paul, Minnesota) and Site 2 (University of California, San Diego, California). At both sites, the goal was to establish an ongoing system to review cases and provide feedback in close to real-time.

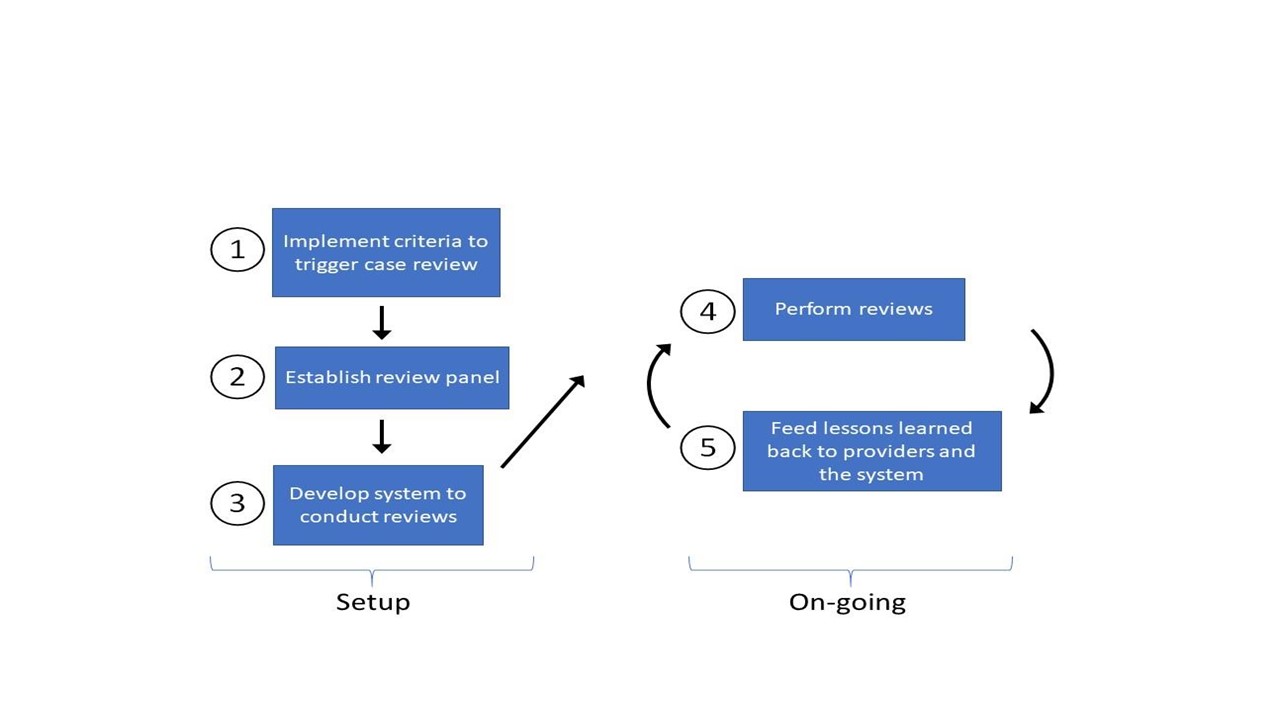

Both approaches used a similar 5-step process to create the review system (Fig).

Step 1: Implement criteria to trigger case reviews—In Site 1, the criteria were developed using local expert opinion whereas Site 2 used criteria created from a modified Delphi process with national and international experts.

Step 2: Establish review panel—Site 1 created a panel with hospital medicine physicians, nurse practitioners and physician assistants. Site 2 created a panel with hospital medicine, emergency medicine and surgery physicians.

Step 3: Develop system to conduct reviews—Site 1 reviewed cases monthly and performed reviews using paper forms. Site 2 reviewed cases twice a month using an online system. Screening for diagnostic error varied by site and both sites categorized contributing factors using Reilly and colleagues’ modified fishbone diagram for diagnostic errors.

Step 4: Perform reviews—Site 1 reviewed 85 cases from June 2017 to May 2018. Site 2 reviewed 350 cases from Jan 2016 to June 2017.

Step 5: Feed lessons learned back to providers and system—Site 1 provided individual feedback to clinicians and sent monthly “pearls” to the Department of Medicine, summarizing areas for improvement. Site 2 discussed cases and lessons with individuals/teams and system-level lessons were shared with the Patient Safety Committee and Risk Management.

Conclusions: Findings to date: The reviews at the two sites identified many opportunities for potential improvement in diagnostic safety [26/85 (42%) at Site 1 and 66/350 (19%) at Site 2]. These opportunities spanned a wide range of scenarios with some common themes of test result management, communication across teams in peri-procedural care and with consultants. More data is being collected and further analysis will be available in a few months.

Case reviews with timely feedback provides useful opportunities to learn and calibrate diagnostic decision-making. Sharing of cases supports a culture of open discussion of opportunities for improvement and learning. The reviews focused on diagnostic safety identify opportunities that may complement those found with more traditional peer review.