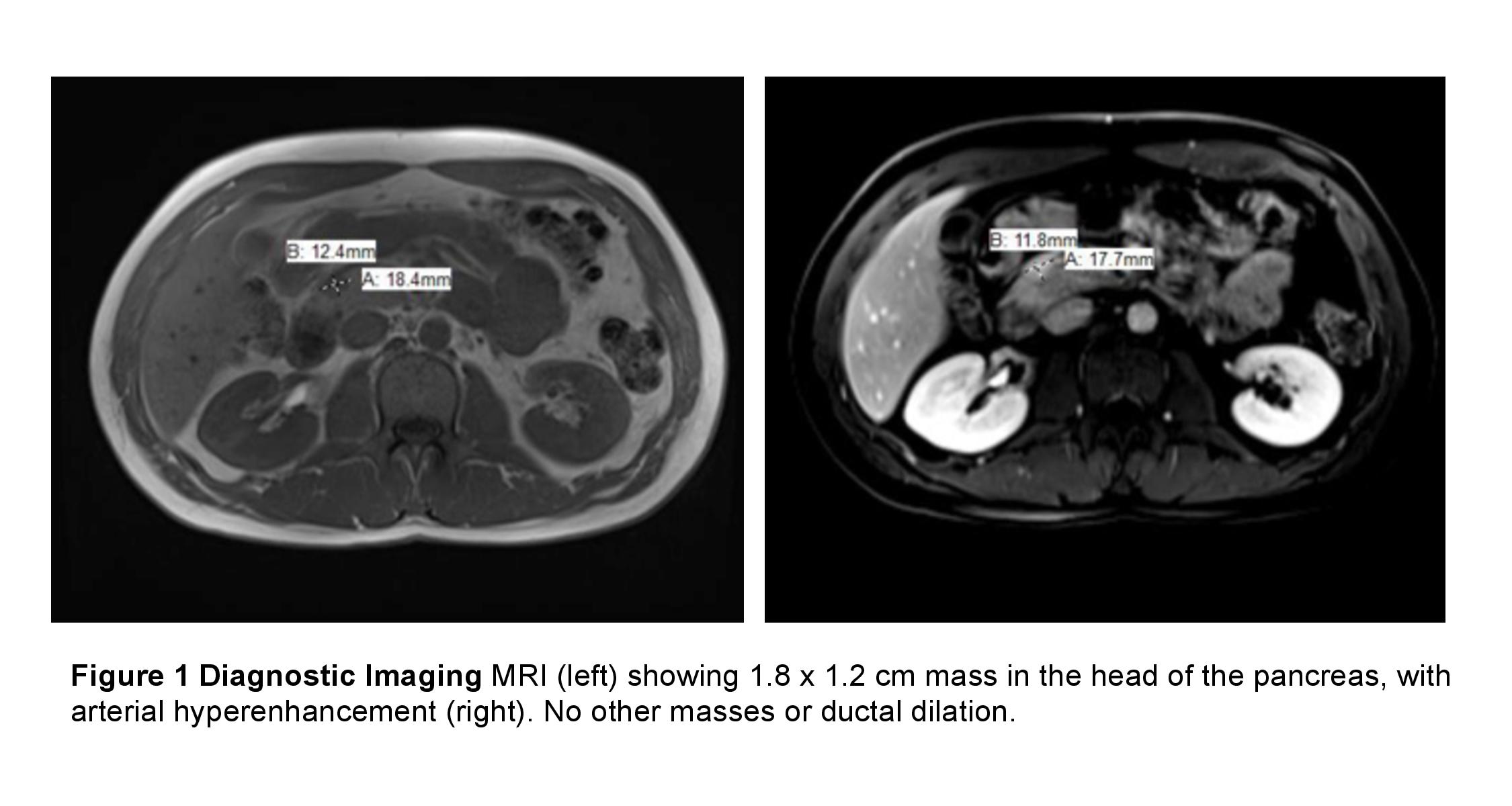

Case Presentation: A 33-year-old male with no significant past medical history was admitted after being found unconscious at his desk with a blood glucose of 28 mg/dL. The patient reported multiple episodes of confusion, slurred speech, and unsteady gait in the context of fasting that was relieved with meals. He also reported almost a decade of high sugar intake – consuming 1.5L of soda and multiple candy bars daily – to prevent lightheadedness. He denied any medication or drug use. On admission, the patient was hemodynamically stable with an unremarkable physical exam. Laboratory values were significant for a glucose of 156 mg/dL. After a 5-hour fast, he had a glucose of 34 mg/dL. Further work-up revealed insulin of 21 uIU/mL, c-peptide of 2.4 ng/mL (RR 0.8- 3.5), B-hydroxybutyric acid <0.2 mmol/L, and a hemoglobin A1c of 4.3%. He had a negative sulfonylurea panel, insulin antibody, toxicology screen, and ethanol level as well as normal thyroid stimulating hormone, liver function tests, complete blood count, and a borderline-normal ACTH stimulation test. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed a hyper-enhancing mass in the head of the pancreas. The patient underwent local resection and enucleation of the mass; pathology confirmed an insulinoma.

Discussion: Insulinomas are rare neuroendocrine tumors that cause hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia. Classically, they present with Whipple’s Triad: neuroglycopenic symptoms, hypoglycemia, and rapid resolution of symptoms with glucose. Due to their rarity, alternative etiologies of hypoglycemia must be considered first. The differential diagnosis is broad and includes sepsis, starvation, alcohol-induced hypoglycemia, adrenal insufficiency, as well as hepatic and renal failure.

Hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia narrows the differential to autoimmune hypoglycemia, exogenous insulin injection, secretagogue ingestion, and insulinoma. Anti-insulin antibody assays and sulfonylurea panel further narrow the differential. Patients with a suspected insulinoma should undergo a supervised fast with serum levels of insulin, c-peptide, and B-hydroxybutyrate drawn once glucose levels reach <50 mg/dl for optimal specificity and sensitivity. An insulinoma is suggested by elevated insulin (≥ 3 uIU/mL) and c-peptide levels (≥ 0.6 ng/mL) plus low B-hydroxybutyrate levels (≤ 2.7 mmol/L).

The next step in diagnosis is localization of the tumor with computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, or endoscopic ultrasound, which has the highest sensitivity and specificity for insulinoma. If these imaging modalities fail, a selective arterial calcium stimulation test can aid in localization. The majority of insulinomas are benign and optimal treatment includes surgical resection.

Conclusions: When a patient presents with Whipple’s triad, the key to diagnosis is thorough history-taking, observation, and careful diagnostic testing. Essential questions include timing of symptoms, comorbidities, medications, and social history. During a supervised fast, inappropriately elevated levels of insulin and c-peptide with low B-hydroxybutyrate establish the diagnosis of insulinoma. Once the diagnosis is confirmed with appropriate imaging, benign solitary insulinomas can be surgically resected.