Case Presentation: A 14-year-old male with history of juvenile ankylosing spondylitis (JAS) and asthma presented to the hospitalist service with four weeks of fever, weight loss, dyspnea, wheezing and cough. He was admitted one week prior for treatment of bilateral pneumonia and was continued on antibiotics after discharge for a ten day course. He had worsening cough, dyspnea and fever several days later, so he presented for further evaluation. Medications included inhaled beclomethasone, albuterol as needed, sulfasalazine started two months prior and adalimumab started one month prior to initial presentation. No tobacco or drug use or recent travel. Vaccinations were up to date.

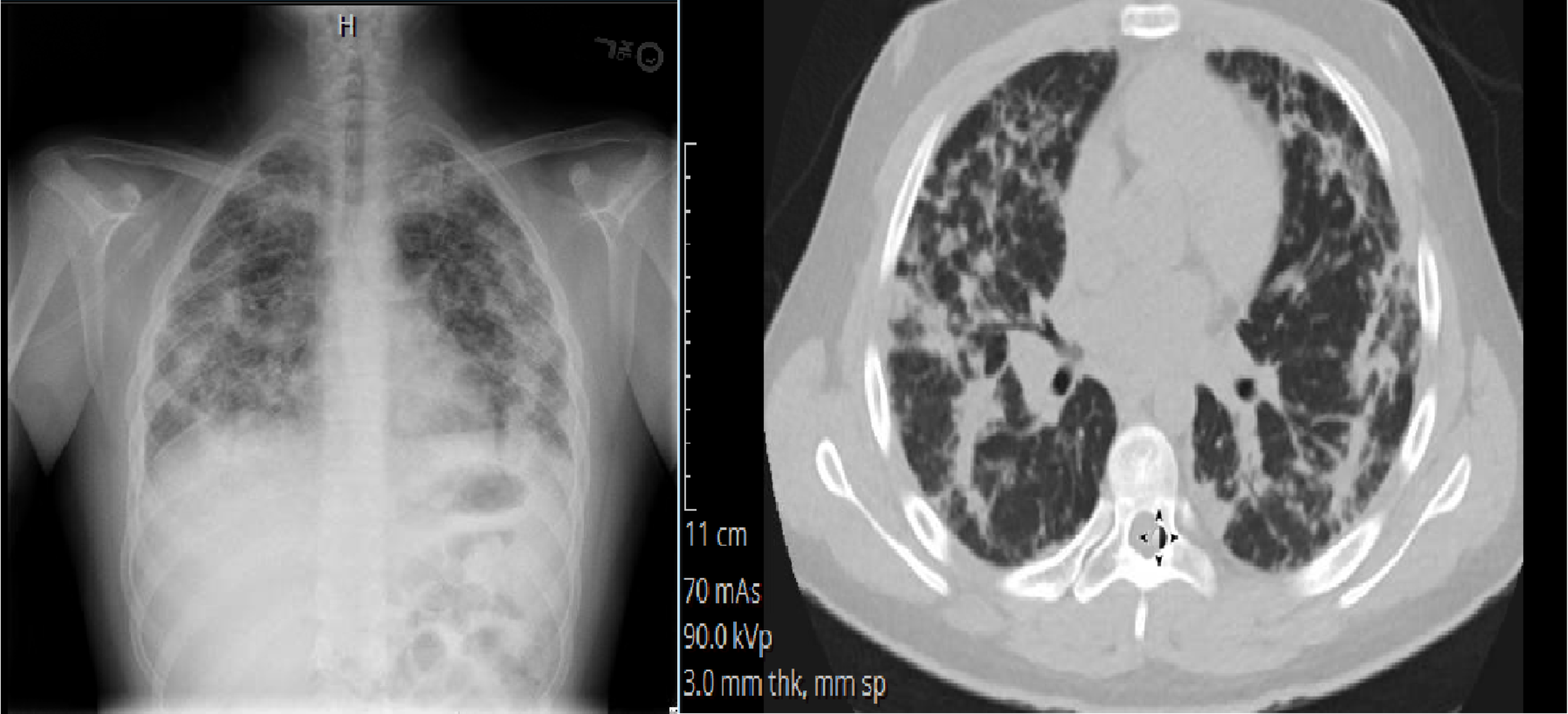

In the emergency room, he was febrile to 38.3 C, tachycardic and tachypneic. He had hypoxia that improved with supplemental oxygen. On exam, he appeared ill with increased work of breathing and had crackles bilaterally. Labs showed WBC 20.8 (absolute eosinophil count 1430), ESR 85, CRP 22.2 and IgE 151. Chest x-ray showed bilateral pulmonary infiltrates most prominent in the peripheral fields. High resolution chest CT showed predominantly peripheral opacification, nodules and reticulations in the lungs. Bronchoscopy with lavage showed 7 WBC and 0% eosinophils; PCRs for bacteria and viruses were negative. Culture grew rare oral flora. Sulfasalazine was discontinued shortly after admission. Pathology from open lung biopsy showed acute/subacute eosinophilic pneumonia without infection or vasculitis. Work-up was negative for various causes of pulmonary eosinophilia including vasculitis, fungi and helminths. He was diagnosed with sulfasalazine-induced acute eosinophilic pneumonia and was treated with three days of IV methylprednisolone prior to discharge, followed by a three month taper of prednisone with resolution of the disease. He has not relapsed off prednisone.

Discussion: Eosinophilic pneumonia is rare in pediatrics. It is classified as acute if presenting within one month of symptoms and chronic if presenting after one month. It can be idiopathic or secondary to medications, fungi, helminths, environmental exposures or systemic disease. Asthma is a known association. In this case, the differential diagnosis was wide, including autoimmune pneumonitis, adalimumab-induced lung toxicity, opportunistic infection and sulfasalazine-induced lung toxicity, which has been described in the literature as a cause of eosinophilic pneumonia.

Eosinophilic pneumonia should be high on the differential diagnosis of a patient admitted to the hospital with pneumonia not improving with antibiotics, peripheral blood eosinophilia, use of associated medications and history of asthma. Our case was unusual in that the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid did not show eosinophils, but the lung biopsy confirmed eosinophilic pneumonia. Drug-induced eosinophilic pneumonia improves once the causative drug is discontinued and resolves even more rapidly with steroids. Adalimumab and other TNF inhibitors have been associated with a variety of noninfectious pulmonary adverse effects, but eosinophilic pneumonia has not been well described in the literature with use of those drugs. In this case, the patient was continued on adalimumab without recurrence of eosinophilic pneumonia.

Conclusions: Eosinophilic pneumonia should be highly considered in the differential diagnosis of a patient on antirheumatic drugs and with a history of asthma presenting with peripheral blood eosinophilia and suspected pneumonia that is not improving with antibiotics.