Background: Functional health literacy includes the ability to receive information, comprehend its meaning, and put it into action. Patients’ health literacy level has been found to be a stronger correlate of health status than education level and other sociodemographic variables. Individuals with below basic/basic health literacy utilize the healthcare system more often and spend more on prescriptions compared to those with above basic literacy. These patients have greater transitional care needs when being discharged to home and are placed at a higher risk of adverse outcomes such as hospital readmission. Health literacy is not routinely evaluated or recorded in inpatient settings. Oftentimes, providers and screening tools only assess whether patients are able to read information. We aimed to expand on this and evaluate if patients admitted to the hospital were able to read information but had trouble comprehending its meaning.

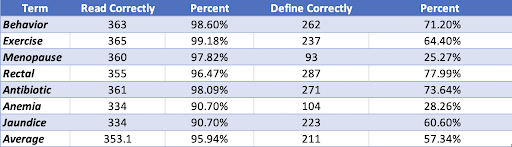

Methods: A cross-sectional study was performed on an inpatient hospital service. From September 2021-October 2022, all admitted adult patients at the hospital were eligible to be screened unless they had a diagnosis of dementia, altered mental status, psychosis, were a patient from the Department of Corrections, had active COVID-19, or were in the ICU. The patients were screened for health literacy by pre-professional health student volunteers using iPads pre-populated with the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine-Short Form (REALM-SF). For grading, 1 point was given for each word the patient was able to read aloud off of the volunteer’s iPad under 5 seconds. To additionally assess comprehension, the patients were asked to define each of the 7 words on the REALM-SF. The patients’ definitions were scored based on similarity to definitions of the 7 terms in the Oxford Dictionary. 1 point was given if the patient’s definition correctly matched that in the dictionary. 0 points were given if the definition was partially correct, wrong, or the patient stated they did not know the definition.

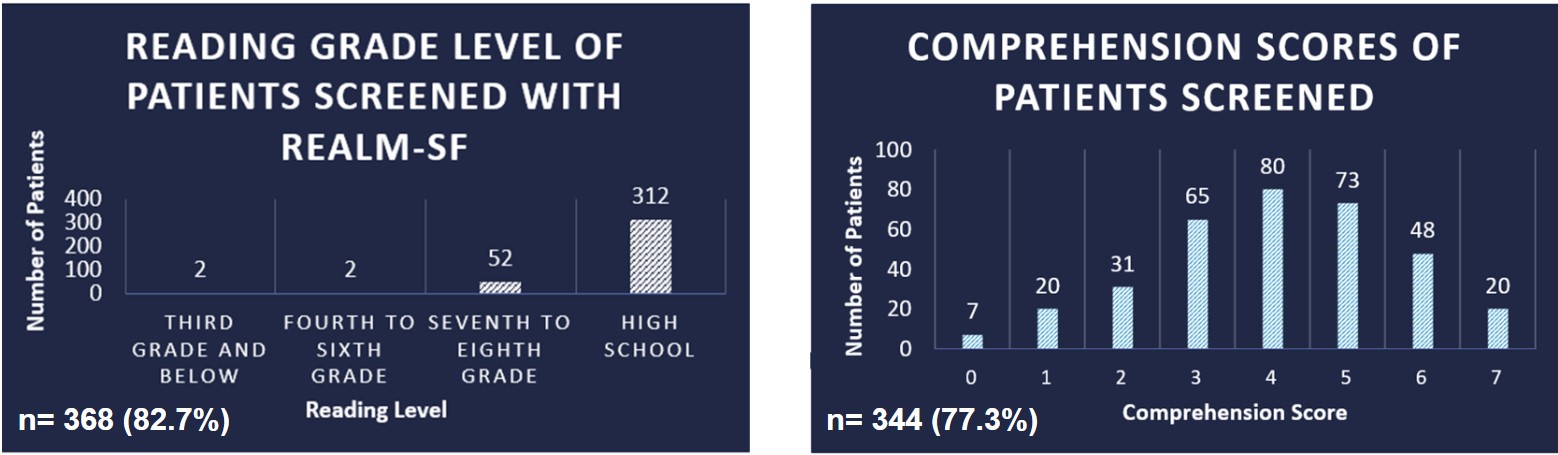

Results: 445 patients were approached by 56 volunteers for health literacy screening. 82.7% or 368 completed the REALM-SF. 344 patients also provided personal demographic information. 4 of these patients were omitted due to incomplete responses. Of the 340 patients included, the majority of patients were White American (79%) and had more than a high school degree (60%). Ultimately, 85% of the 368 patients screened for health literacy showed a high school reading level, however, only 6% of the 344 patients who defined each word matched the correct definitions. A greater proportion of patients who scored the best on comprehension had a higher level of education: 75% completed greater than high school as compared to the 55% of those with the lowest comprehension. Additionally, a smaller proportion of patients who scored the best on comprehension were minorities: 15% versus the 31% of minorities who scored the least on comprehension.

Conclusions: There is a major discrepancy between the percent of patients able to correctly read (85%) versus correctly define (6%) all medical terms. Although a patient may be able to read the materials, they may not necessarily comprehend the information. Physicians should attempt techniques such as the teach back method or assess if patients have any questions about their health frequently as our data supports that many people can read the information, but may not be able to actually comprehend it.