Background: Thrombotic disorders, such as venous thromboembolism (VTE) and ischemic stroke are highly prevalent conditions. In many cases, an underlying inciting risk factor is clearly visible that can explain the thrombotic event. When a clear explanation is not found, diagnoses such as “idiopathic VTE” and “cryptogenic stroke” are made. Except when there is a concern for antiphospholipid syndrome (APS), the American Society of Hematology (ASH) Choosing Wisely Campaign recommends against routine thrombophilia testing in the inpatient setting (1). Results in this setting can be inaccurate and rarely lead to management changes. We sought to define the prevalence/magnitude of such inappropriate thrombophilia testing and its financial impact on our institution.

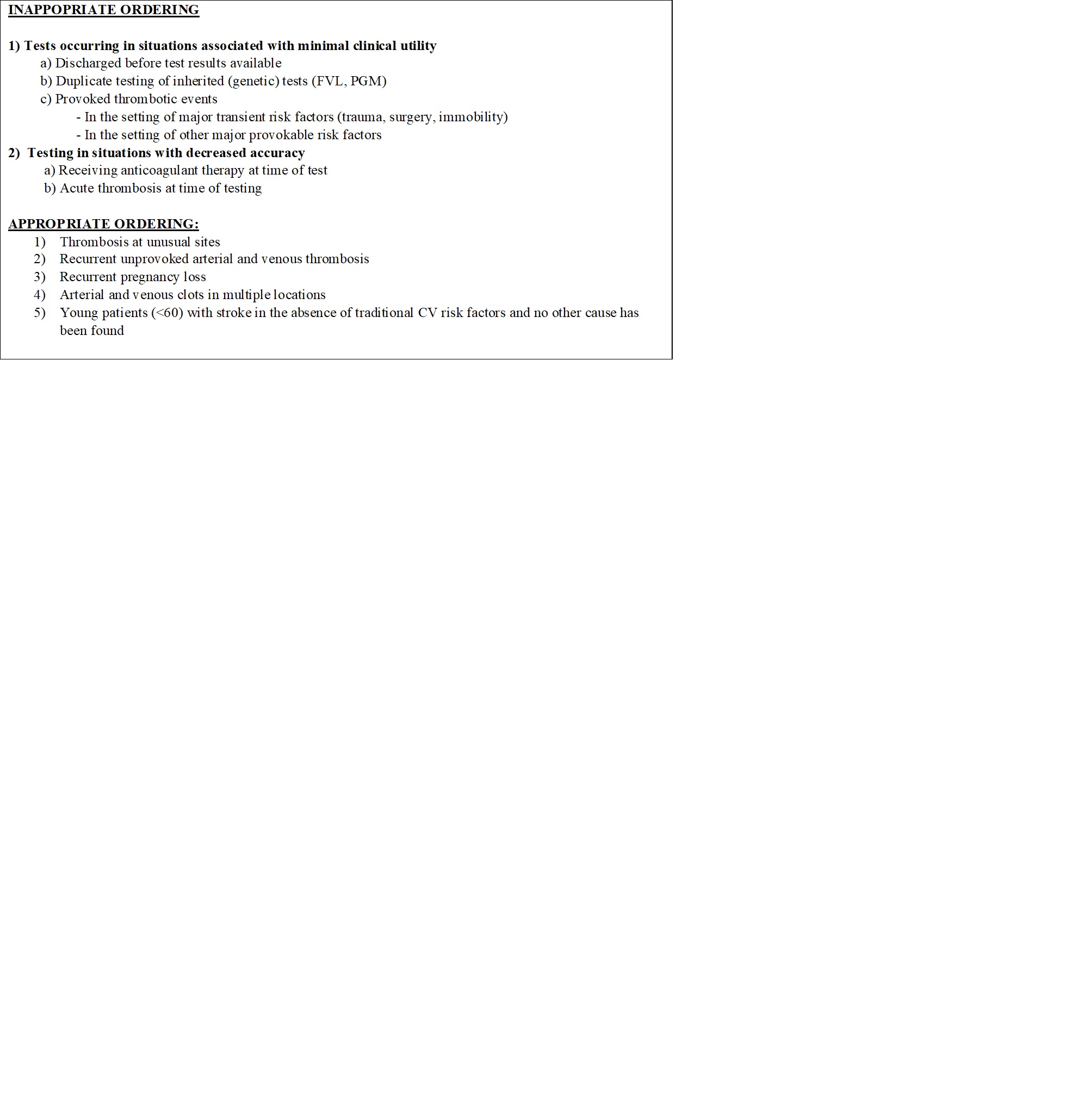

Methods: A retrospective study was conducted at our community-based hospital from January 2016-December 2019. The inclusion criteria included all patients over the age of 18 years old with thrombophilia testing performed. Exclusions were patients with incomplete chart documentation. Thrombophilia testing included inherited thrombophilias (Factor V Leiden, Prothrombin 202010 gene mutation, antithrombin, Protein C and Protein S levels) or acquired thrombophilias (cardiolipin G and M, beta-2 glycoprotein 1 immunoglobulin G and M, dilute Russel viper venom time, and lupus anticoagulant). The criteria for test appropriateness was defined using major society guidelines and current evidence (Table 1) (2,3). The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) was used to perform cost analysis (4).

Results: Out of 523 patients, 405 fit the inclusion criteria. Pulmonary embolism was the most common admitting diagnosis at 21.5% (90/417)*. In 61% of the cases, a Hematology consult was not placed prior to testing. In cases where a consult was placed, 68% of the time, the consultant did not request testing. There was no change in anticoagulation or management in 93% of patients (378/405). Appropriate testing was done in 20% (82/405), with a change in type or duration of anticoagulation in 28 patients (28/405, 6.9%). A chi-square test was used to examine differences in rates of change in anticoagulation type or duration between patients with provoked arterial, unprovoked arterial, provoked venous, and unprovoked venous thrombosis. Statistically significant results were observed (<0.0001). Patients with provoked arterial and venous thrombosis were significantly less likely to have changes compared to those with unprovoked arterial or venous thrombosis (2.21% vs 9.29%) and (2.63% vs 7.90%) respectively. Of the total $128,263 spent on 2,645 tests, $109,408 was expended on 1968 inappropriate tests. *The number of diagnoses is more than the total number of patients (405), as a patient may have had more than one diagnosis on admission

Conclusions: The practice of thrombophilia testing is inconsistent with current practice guidelines. Testing did not influence management and proved to be done in situations with little clinical utility. Strategies are needed at the institution-wide level to improve testing practices. The EMR will be updated to include a thrombophilia panel with the most commonly ordered tests with a popup box to educate health care providers from ordering unnecessary tests. However, if testing is warranted, recommendations will be made to consider a Hematology consult prior to testing.