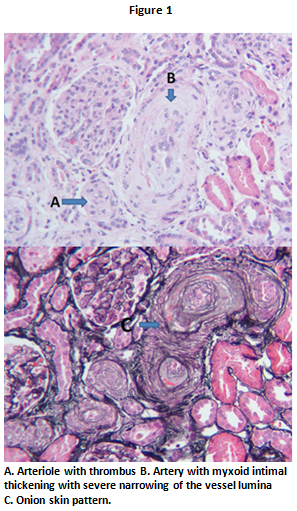

Case Presentation: A 44-year-old male presented to the Emergency Department after having a witnessed seizure. There were no precipitating events and previous blood tests were normal. His blood pressure (BP) on arrival was 255/154 mmHg. Labs showed a creatinine (Cr) of 2.2 mg/dL, hemoglobin 9 g/dl, platelet 553 k/uL, low-normal haptoglobin of 31 mg/dL, and mildly elevated lactate dehydrogenase 284 U/L. He had microscopic hematuria and 1.3 gram proteinuria. Urine drug screen was negative. An ultrasound of the kidneys was normal. He was started on a Nicardipine drip and his BP improved. He was transitioned to oral medications. Given his persistent acute kidney injury (AKI) and hematuria, a renal biopsy was done and showed pathology consistent with thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) and arterioles showing an “onion-skin” pattern (Figure 1). The initial working diagnosis was Atypical Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome (aHUS). After resolution of his mental status changes, he described Raynaud’s symptoms for years and tight skin around his digits. On closer exam, he had mild sclerodactyly of the fingers. An autoimmune workup revealed a positive ANA, mildly elevated anti-dsDNA, and positive SCL-70 antibody. Based on clinical findings, labs, and biopsy results he was diagnosed with scleroderma and the event was attributed to scleroderma renal crisis (SRC). His AKI was thought secondary to TMA. His medications were optimized with addition of an ace-inhibitor (ACE-i). His Cr improved and his BP remained controlled on follow up.

Discussion: Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is characterized by inflammation and fibrosis of the skin, but can affect multiple organs. SSc is classified by extent of skin involvement: limited cutaneous (lcSSc) and diffuse cutaneous (dcSSc). SRC is a life-threatening complication and presents with acute onset of severe HTN, hypertensive encephalopathy, and AKI. Seizures may be the first manifestation. Intimal proliferation and thickening of vessels results in concentric hypertrophy or “onion-skin” appearance on histology. SRC also leads to TMA with abnormalities in the vessel wall of arterioles and capillaries leading to microvascular thrombosis. SRC occurs in up to 20% of patients with dcSSc but in <2% of patients with lcSSc. Rarely is SRC the initial manifestation of SSc. TMA is a pathological diagnosis, classically associated with Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome (HUS) but also seen in pregnancy, malignant hypertension, drug toxicity, and systemic autoimmune disease. Treatment is specific to the etiology of the disease process and requires clinical-pathological correlation. This case is rare in that SRC was the initial clinical manifestation of his SSc and occurred in the setting of lcSSc. This case highlights the importance of history and physical exam in medical decision-making. The kidney biopsy diagnosis of TMA is not specific for SRC and thus required clinical context, specifically his skin findings and positive serology. Prompt initiation of an ACE-i is critical in patients with SRC.

Conclusions: Thrombotic Microangiopathy is a pathological diagnosis, which requires clinical correlation for treatment. A thorough history and exam is critical to avoid a delay in diagnosis and direct appropriate treatment.