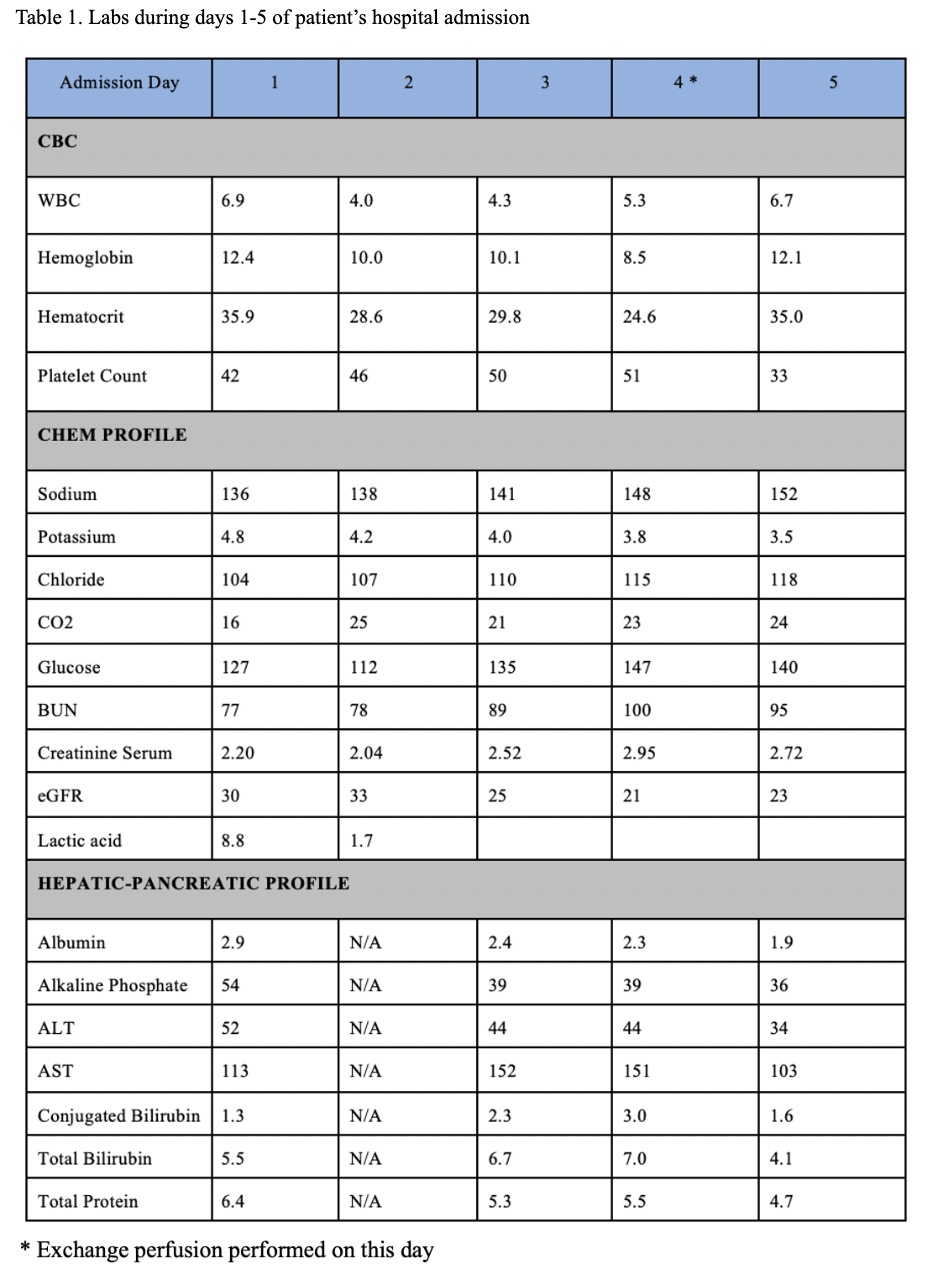

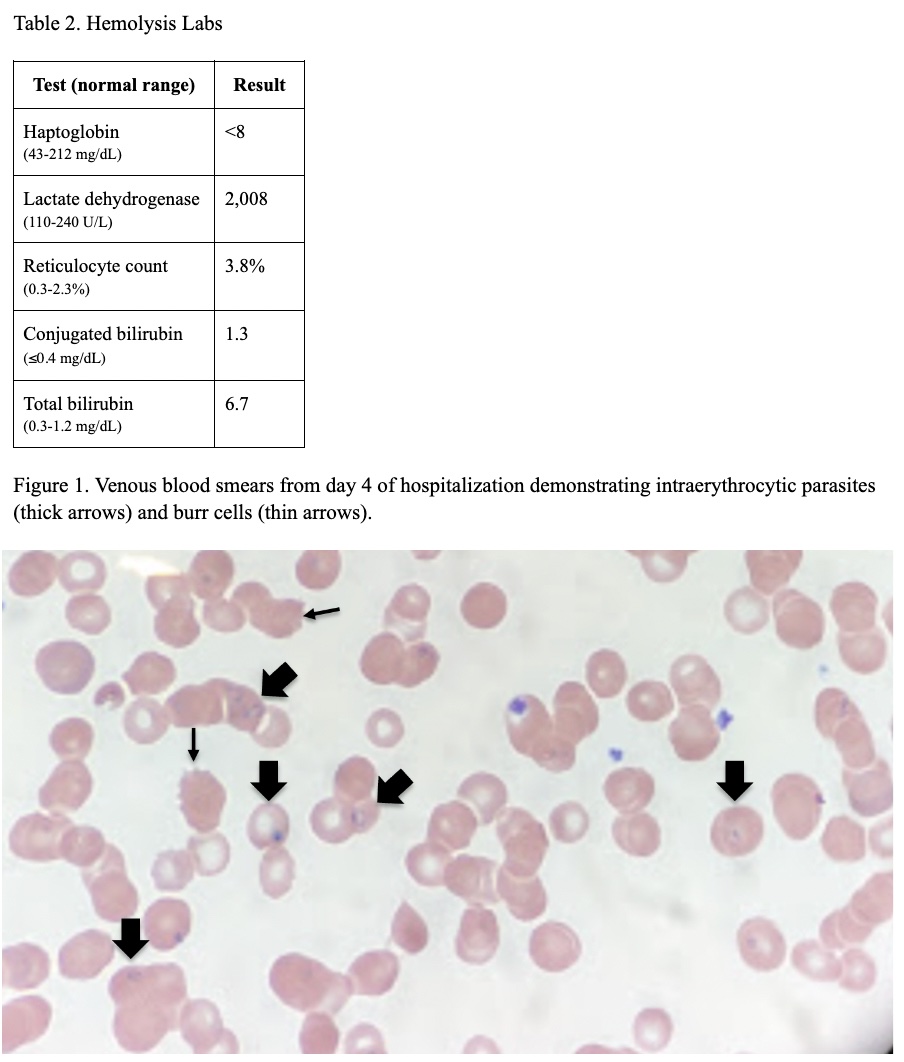

Case Presentation: A man in his late 70s presented to the emergency department after multiple falls and new onset altered mental status. Past medical history included hypertension, hyperlipidemia, chronic kidney disease (CKD) stage III, and previous infection with anaplasmosis over a decade prior.On clinical exam, the patient was afebrile, hypoxic, and meeting SIRS criteria with tachycardia and tachypnea. He was jaundiced, with scleral icterus, and mild diffuse abdominal tenderness. His laboratory findings (table 1) revealed conjugated hyperbilirubinemia, elevated transaminases, anemia, thrombocytopenia, elevated lactate to 8.8, azotemia, and acute kidney injury. The patient was admitted to internal medicine for hyperbilirubinemia with possible sepsis and empirically started on vancomycin, piperacillin-tazobactam, and doxycycline. At the time of presentation, the initial working diagnosis was sepsis secondary to cholecystitis or hepatitis. However, his altered mental status did not improve with fluid resuscitation and 3 days of empiric antibiotics. Moreover, imaging did not support a hepatobiliary pathology despite the hyperbilirubinemia and elevated transaminases. Given this fact, along with the labs consistent with hemolysis and acute tubular necrosis (table 2), hematology was consulted to determine an underlying cause of hemolytic anemia. Tick-borne disease panels had been sent on admission, and on the third day of his hospitalization, babesiosis resulted positive. This was confirmed on peripheral blood smear (figure 1) and patient was started on a 7-day course of atovaquone and azithromycin. His initial blood parasite level was 8%, so transfusion medicine recommended exchange transfusion. On hospital day 4, an HD line was placed and 2,853 mL of red blood cells were used during exchange, for a goal of replacing 70% of his red cell population. This improved his anemia (as seen in his day 5 labs in table 1) and brought the parasite level down to 1.6%, which then continued to trend down to zero as he received medical treatment. Given that the first negative blood smear was on the last day of treatment, infectious disease recommended continuing the antibiotic regimen for 10 additional days from the negative smear. Thus, the patient ultimately completed a 17-day course of atovaquone and azithromycin.

Discussion: This case raised clinical questions about determining management and length of treatment in a patient with high parasite burden. RBC exchange transfusion is a proven therapy for malaria, but its use in treatment for babesiosis remains ill-defined (7). The Infectious Disease Society of America 2006 guidelines recommend RBC exchange in cases of high-grade parasitemia (>10%), significant hemolysis, or end-organ disease in the liver, kidney, or lungs (8,9). In this case, the patient was found to have a high parasite burden, worsening anemia, altered mental status, acute kidney injury, and elevated transaminases, all of which contributed to the decision to use RBC exchange in his treatment. Furthermore, although the standard length of antibiotic treatment is 7-10 days of Atovaquone and Azithromycin or Clindamycin (8), this case also highlighted the need for re-evaluation and adjustment of the antibiotic time course in a patient with high parasite burden.

Conclusions: In patients with severe babesiosis and high parasite burden, red blood cell exchange can rapidly reduce parasite load. Exchange transfusion, in combination an elaborate antibiotic regimen, can help lead to successful treatment.