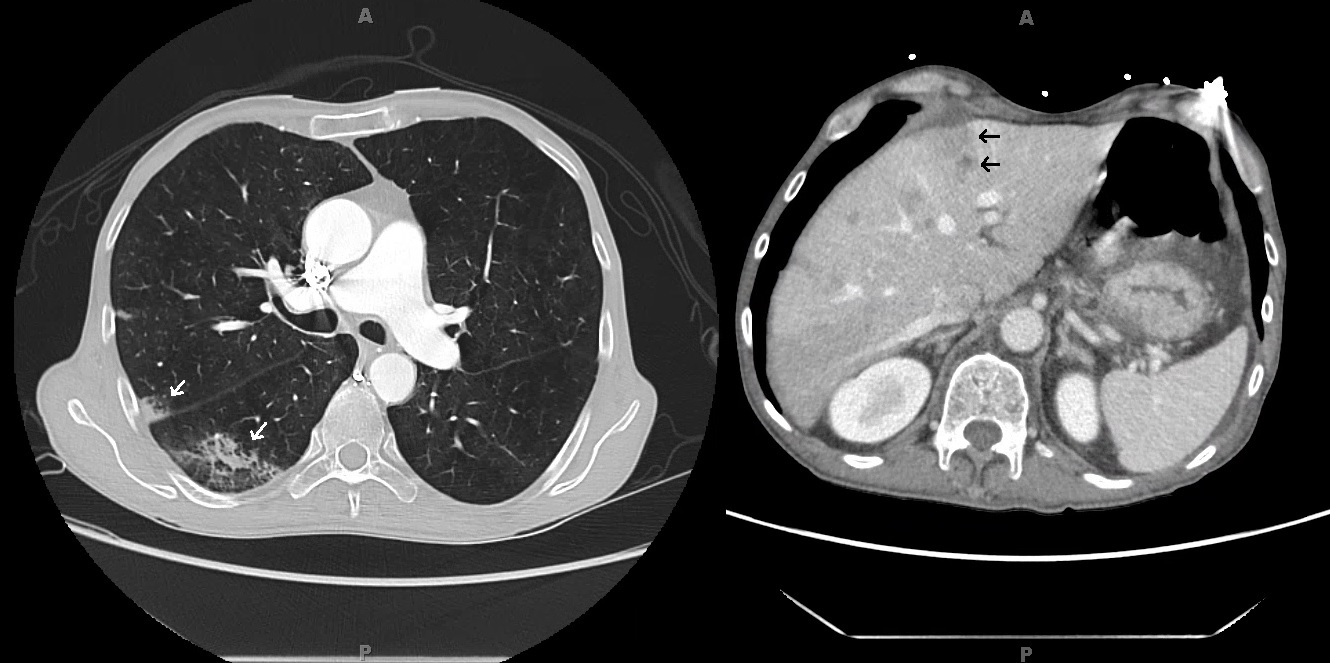

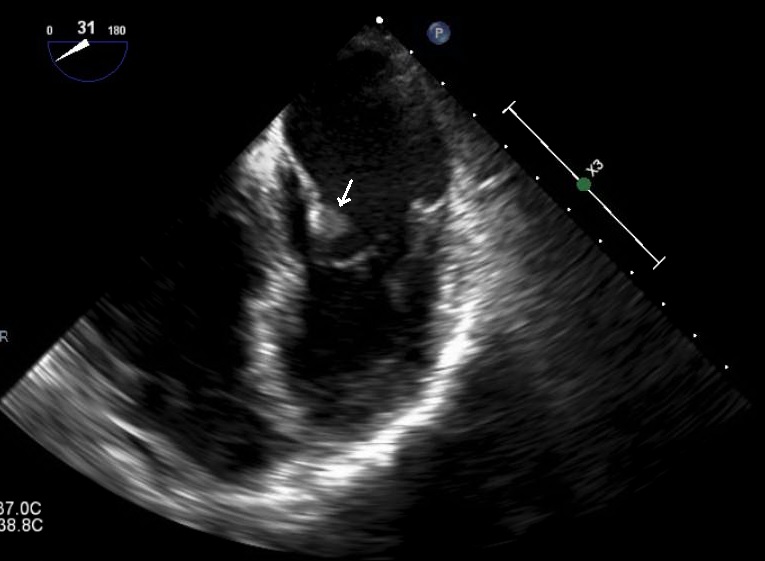

Case Presentation: A 52 year-old man was hospitalized for hypoxia one month after surgery for ruptured appendicitis. He also reported abdominal pain and steatorrhea along with a 50 pound weight loss in five months. On exam he was anicteric but cachectic. CT pulmonary angiogram on admission revealed peripheral-based pulmonary lesions concerning for septic emboli and incidental hepatic lesions. A follow-up CT of the liver revealed multiple small liver lesions and a possible hypo-attenuating pancreatic lesion. His Cancer Antigen 19-9 was 777 U/ml and fecal elastase was undetectable. Our main concern was for pancreatic adenocarcinoma but we considered septic emboli in our differential given his recent ruptured appendicitis. A CT-guided liver biopsy was non-diagnostic with negative cultures of the tissue as well as the blood. Endoscopic ultrasound failed to confirm the patient’s liver lesions. Patient was discharged and readmitted with worsening symptoms and CT findings. Transesophageal echocardiogram revealed thickening and probable small vegetations of the mitral and aortic valves suggestive of non-bacterial thrombotic endocarditis (NBTE). MRI of the abdomen showed a 9×6 mm lesion in the pancreatic head. A repeat liver biopsy resulted with moderately differentiated mucin-producing pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Patient’s repeat CA-19-9 had increased to 6008 U/ml one month after his initial presentation. The patient was diagnosed with metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma with systemic emboli from NBTE. He elected to pursue hospice services at home and subsequently discharged from the hospital.

Discussion: When hematogenous spread of infection is on the differential with malignancy, one must be cognizant of NBTE as a cause of systemic embolization. Up to 80% NBTE causes are due to advanced malignancy with lupus coming in a distant second. It is estimated that 10% of patients with mucin-producing adenocarcinoma have NBTE. This patient’s presentation favored pancreatic adenocarcinoma considering his profound weight loss, steatorrhea and elevated CA-19-9. The variation in the appearance of his hepatic and pancreatic lesions on different imaging modalities and the negative initial liver biopsy delayed the diagnosis as extensive infectious workup for septic emboli was pursued. The prognosis of NBTE is poor due to its association with advanced malignancy. As illustrated by this patient’s case, mortality in pancreatic adenocarcinoma approaches 80% in the first year of diagnosis due to its late presentation.

Conclusions: Although septic emboli and infective endocarditis are more common in the general patient population, NBTE with resultant embolic events should be considered in any patient with a concern for advanced malignancy. In this case, MRI was superior for soft tissue discrimination over CT and ultrasound. A non-diagnostic biopsy in the setting of high clinical suspicion for malignancy is likely to represent sampling error, especially in cases of NBTE.