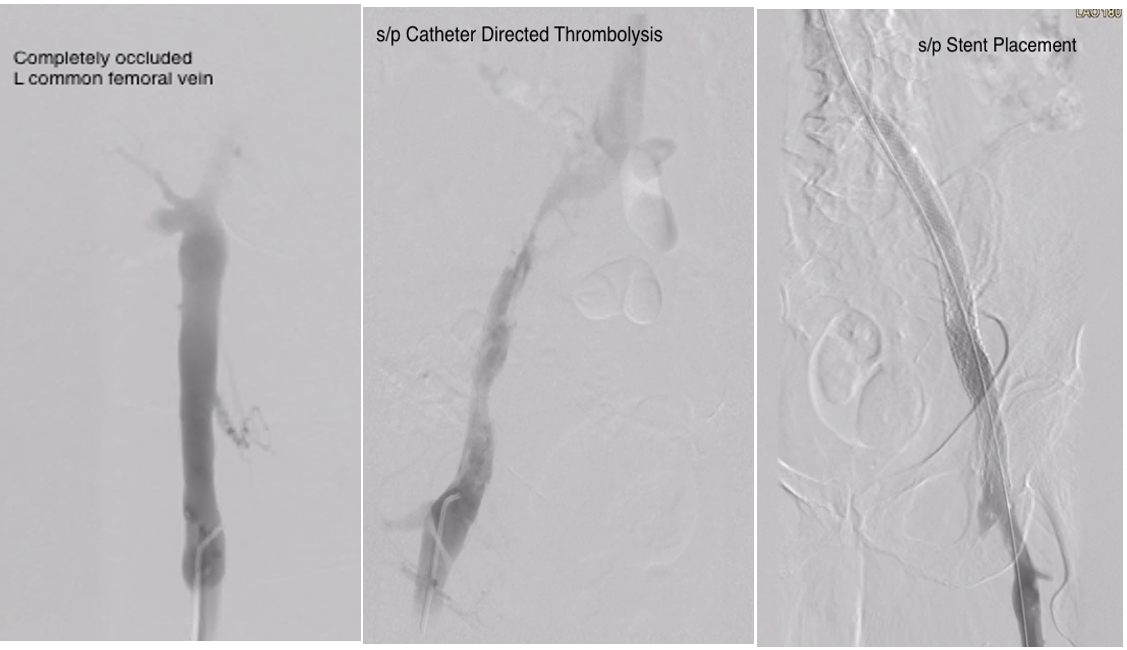

Case Presentation: 73 years old Caucasian female with a remote history of hysterectomy, and cesarean section presented with new left leg swelling and pain that began the previous day. She described the pain to be throbbing, localized, 8/10 in intensity, continuous, and not responding to ibuprofen. She denied any personal/family history of clots, recent travel, or prolonged periods of immobilization. She is a prior smoker, quit 47 years back. Reports no medications or supplements. Exam showed a non-tender, swollen left leg with erythema and edema extending up to the groin, with intact pedal pulses. Venous doppler ultrasound exam demonstrated thrombi extending from left calf veins up to the left common femoral vein. CTA of the chest was without any identifiable pulmonary emboli. Empiric treatment with enoxaparin was initiated alongside vascular surgery consultation. She underwent percutaneous thrombectomy and was further evaluated with venogram/intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) that showed severe stenosis at the left common iliac vein consistent with May-Thurner syndrome. Further treatment with catheter-directed thrombolysis (CDT) was followed with a venogram that showed >90% stenosis in the left common iliac vein extending to the caval confluence proximally and left external iliac vein distally. Self-expanding metal stents to the left common iliac and external iliac veins were placed and started on rivaroxaban and clopidogrel. Three days later, she presented with a recurrence of initial symptoms and was noted to have a stent-occluding thrombus. While being treated with CDT and heparin drip, she developed blood loss anemia, evidenced by a drop in hemoglobin from a baseline of 12 to 6.9 g/dl that required a blood transfusion. Another compressive lesion was identified at the left common femoral vein and a second set of self-expanding metal stents was deployed and followed with post-dilatation balloon angioplasty.

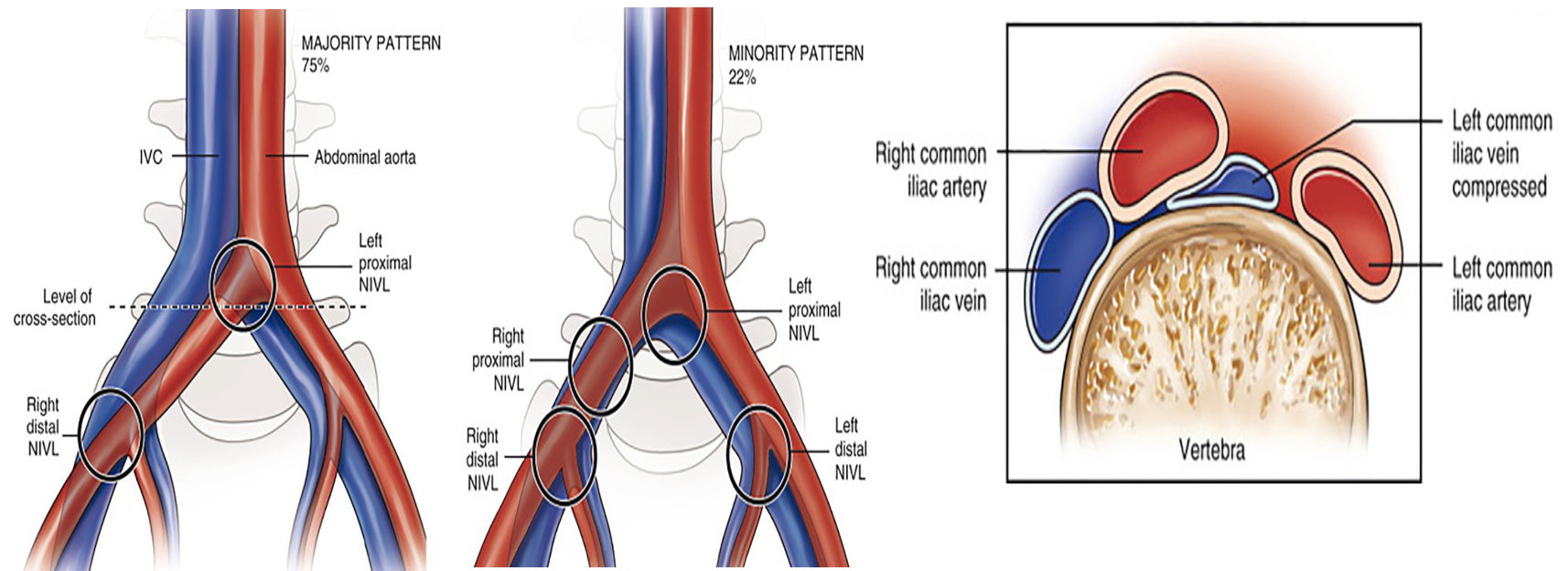

Discussion: May-Thurner or Cockett syndrome, initially described in 1957, commonly presents with lower extremity swelling and pain, stemming from mechanical compression or a non-thrombotic lesion, that eventually forms venous spurs in the iliocaval venous territory, leading to venous hypertension. It may also present with venous claudication, venous ulcers, and rarely with pelvic congestion syndrome, retroperitoneal hematoma from a ruptured iliac vein, or a cryptogenic stroke.1 Besides a strong female preponderance (about 2-5:1), other risk factors include scoliosis, dehydration, coagulation disorders, pregnancy, contraceptive use, and cumulative radiation exposure.1 Diagnosis requires the demonstration of the anatomic venous stenotic lesion. When a thrombus is present, thrombolysis or open thrombectomy is preferred and followed by angioplasty, stenting, prompt anticoagulation, and antiplatelet therapy. Lifetime anticoagulation may be necessary for recurrent thrombosis. In the absence of a clot, non-invasive evaluation with venous phase MR/CT venography with eventual stenting and antiplatelet therapy is an alternative approach.2

Conclusions: The persistence or recurrence of deep vein thrombosis should trigger suspicion for May-Thurner Syndrome irrespective of the age of presentation before a conclusion of treatment failure is arrived at. Correction of the anatomic abnormality and restoring venous patency are essential to addressing the stasis component of Virchow’s triad and preventing further recurrence.