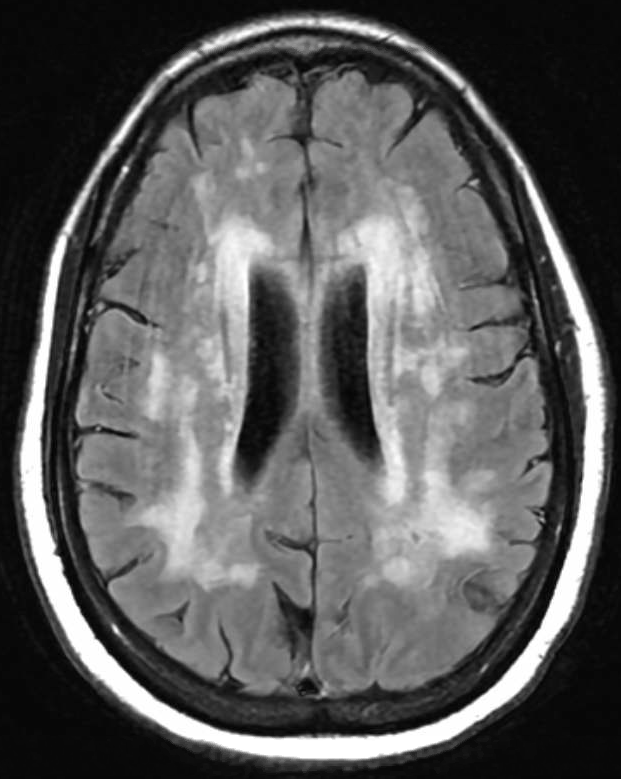

Case Presentation: A 45-year-old woman initially presented with sudden dizziness upon sitting up, followed by persistent holocranial pressure headaches, blurry vision, and visual distortions resembling a kaleidoscope effect. The patient has primarily received outpatient care for persistent headaches and has undergone frequent monitoring due to worsening cognitive decline for which she was referred to a neurologist. She denied sensory or motor deficits, falls, or family history. Initial CT head revealed white matter alterations and MRI brain revealed severe leukoencephalopathy affecting various brain regions raising concerns about Cerebral Autosomal Dominant Arteriopathy With Subcortical Infarcts And Leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL) or vasculitis (Figure 1). Further tests, including cerebrospinal fluid analysis and genetic screening, confirmed a heterozygous mutation in the NOTCH3 gene, which is strongly associated with CADASIL.

Discussion: Amidst the intricate landscape of neurological conditions, CADASIL emerges as a complex puzzle. This uncommon genetic disorder affects small blood vessels, typically revealing its neurological symptoms in adulthood. For nearly half of those affected by CADASIL, the onset is marked by migraines, followed by recurrent ischemic strokes and transient attacks (1). As the condition progresses, cognitive decline becomes evident, advancing to dementia in roughly 75% of cases. It stands as the most prevalent monogenic autosomal-dominant cerebral small-vessel disorder. CADASIL originates from mutations within the NOTCH3 gene, showcasing a diverse array of neurological symptoms (2). This mutation results in misfolding and aggregation of proteins that trigger abnormal recruitment of extracellular matrix proteins like clusterin and collagen 18 α1. Clinically, CADASIL manifests as central nervous system impairments due to recurrent ischemic strokes, often accompanied by diffuse white matter lesions and subcortical infarcts. Its uniqueness among other conditions lies in the accumulation of granular osmiophilic material (GOM) within the brain’s vasculature, acting as its pathological hallmark (3). GOM deposits impede interstitial fluid drainage, leading to perivascular damage, impairment of the blood-brain barrier, thickening of vessel walls, and enlargement of perivascular spaces. These changes appear as symmetrical and bilateral white matter hyperintensities on T2W and FLAIR sequences (4). They primarily affect the frontal, parietal, and anterior temporal regions, followed by the external capsule. Additionally, characteristic lacunar infarcts are predominantly found in subcortical brain regions like the thalamus, basal ganglia, and pons, significantly associated with cognitive impairment. The number of these infarcts detected on MRI serves as a predictive factor. CADASIL diagnosis encompasses clinical, genetic, and pathological criteria. New diagnostic criteria incorporate age of onset, clinical findings, and genetic confirmation (5).

Conclusions: Given its rarity, vigilance for this diagnosis is crucial and must be underscored in the purview of hospitalists and primary care physicians. Therefore, it should be considered in the diagnosis for patients displaying new-onset cognitive decline or stroke-like symptoms, especially if they lack significant previous risk factors and show suggestive imaging findings.