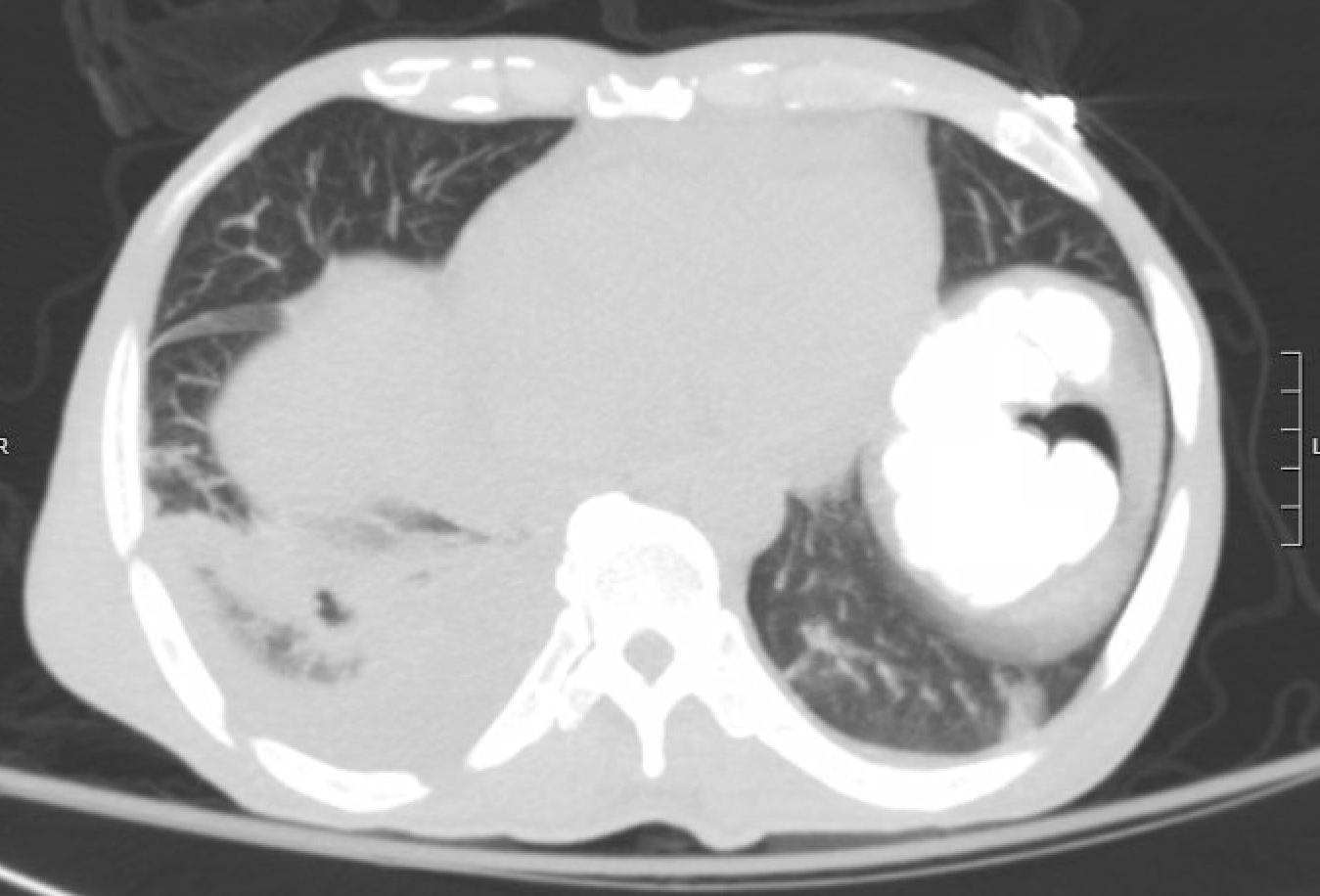

Case Presentation: A 57-year-old Honduran male with no past medical history presented with two weeks of recurrent fevers, dyspnea, bilateral blurred vision, and pain in his low back, flank, and abdomen. Chest X-ray revealed a round opacity over the right lower lung. CT chest, abdomen, and pelvis showed patchy consolidation in the right lower lobe (RLL), bilateral pleural effusions, and perinephric stranding. He was admitted for hypoxemia with suspected community acquired pneumonia. Ophthalmology noted xerophthalmia and bilateral retinal detachments, prompting an ANA and Quantiferon, both of which were positive. Follow-up labs were significant for ESR 125, CRP 9, C3 of 39 (low), undetectable C4. Sputum and pleural fluid tuberculosis (TB) PCR and AFB smears were negative. Subsequent CTA of the chest revealed RLL pulmonary embolism and thrombosis of the left internal jugular and brachiocephalic veins.Laboratory findings led to consultation with Infectious Disease (ID) and Rheumatology. ID did not favor TB as the primary diagnosis given the patient’s paucity of risk factors with negative PCR and AFB smears. A lymph node biopsy was also unrevealing. Rheumatology noted his presentation was atypical for a sentinel episode of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE); however, after anti-Smith, anti-dsDNA, RNP, and SSA antibodies were positive and the patient had new onset pericardial effusion the decision was made to initiate both systemic corticosteroids for SLE and rifampin for latent TB. After 16 days on 20mg prednisone, the patient then developed an unstable arrhythmia and repeat CT angiography showed a cavitary pulmonary lesion, raising concern for transformation from latent to active TB. He was transitioned to RIPE therapy and discharged to home four days later. Outpatient renal biopsy confirmed lupus nephritis and a later thoracentesis confirmed active tuberculosis.

Discussion: Late onset SLE, defined as SLE diagnosed at age 50 or later, represents fewer than 1 in 5 SLE cases. As in this patient, it presents more often with serositis and lung involvement and less with arthritis or malar rash thus many cases will fall outside of the typical diagnostic heuristic for SLE. Mortality from late-onset SLE is estimated to be 29% versus 5% for those diagnosed prior to age 50, most often from cardiovascular disease and infection. With some studies reporting a misdiagnosis rate up to 70%, avoiding anchoring bias is particularly important; here this was accomplished by interdisciplinary collaboration and reassessing the differential diagnosis to incorporate new findings. Also notable was the rapid transition from latent to active TB after steroid initiation. Current guidelines do not require testing for latent TB prior to initiating steroids in any patient population. It begs further discussion of which cumulative risk factors may impact the risk of transforming latent to active TB as even low dose, short-term steroid initiation in the setting of hypocomplementemia and advanced age may have led to activation.

Conclusions: Late onset SLE is a challenging diagnosis, both for its demographic and atypical presentation. It may present in the hospital as an unexpected cardiovascular or infectious event thus requiring clinicians to be responsive to findings inconsistent with initial assumptions. Adaptability and collaboration also aided in reassessing the initial decision to treat for latent TB. This case also bears relevance to further discussion of screening for TB in patients treated with corticosteroids for autoimmune diseases.