Background: Procalcitonin (PCT) testing has been shown in randomized trials to decrease antibiotic exposure and be a reliable predictor of clinical response to antibiotics in lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI) and sepsis. Although studied to guide antibiotic discontinuation in LRTI and sepsis, optimal strategies for introducing PCT into “real-world” clinical use are unknown. Our study describes the implementation and use of PCT testing as it was introduced at our urban academic medical center.

Methods: Once daily PCT testing became available for the purpose of de-escalation of antibiotics at our institution in 2018, with turnaround time 6-14 hours from time of ordering. A multidisciplinary group of hospitalists, antimicrobial stewardship pharmacists, and subspecialty physicians (infectious disease and critical care) developed local guidelines for appropriate PCT use. These guidelines were incorporated into a PCT ordering algorithm and embedded into the electronic health record. Internal medicine residents, hospitalists, and ICU providers received formal didactic education on PCT use and interpretation. Nine months after roll-out, we sent an electronic survey to these physicians to assess knowledge and clinical practice patterns.Additionally, we identified a cohort of patients from the initial 9-month implementation period who met all of the following: admission diagnoses of sepsis and/or LRTI; PCT tests obtained within the first 24 hours of hospitalization; and treated with antibiotics. Our primary outcome was antibiotic de-escalation, defined as discontinuation of antibiotics within 24 hours of negative PCT result (<0.25). We used logistic regression to compare the likelihood of receiving antibiotics based on test result patterns.

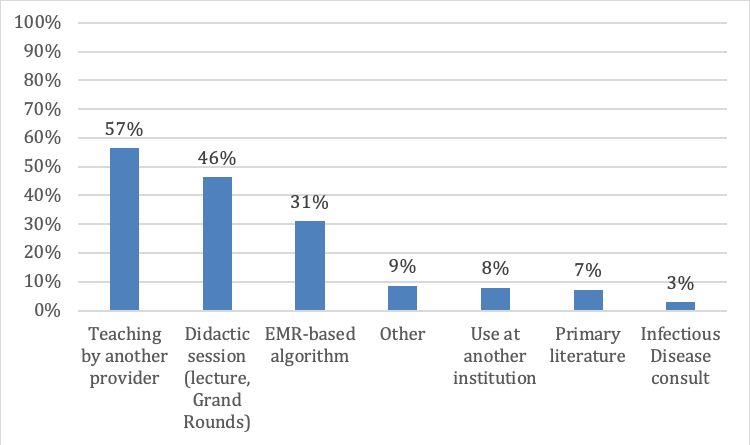

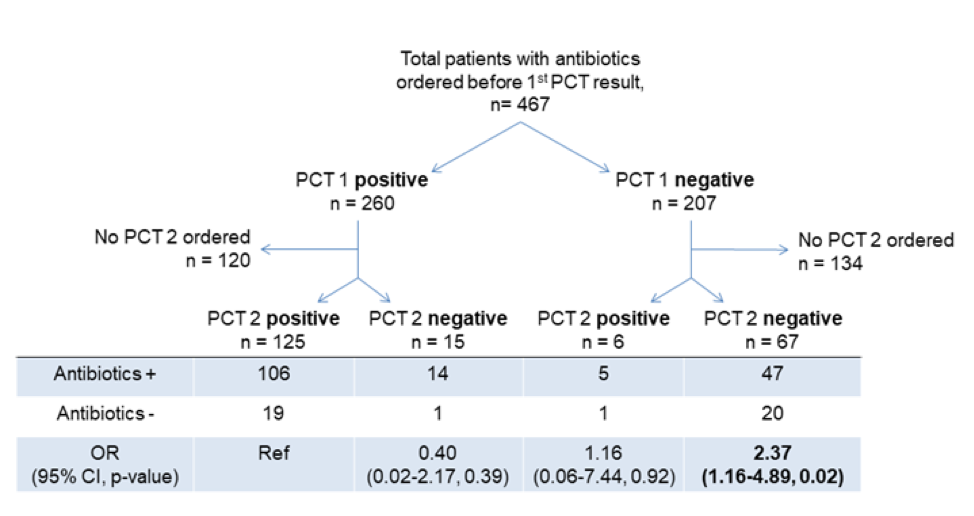

Results: Out of 316 surveys sent, 138 were completed (44% response rate; 14 ICU providers, 57 hospitalists, and 67 internal medicine residents). Physicians reported ordering PCT more often for LRTI than for sepsis, though in both groups use was estimated to be less than half of cases. Providers reported feeling neutral to somewhat comfortable in PCT interpretation for both LRTI and sepsis. Physicians reported learning the most about appropriate PCT use from other providers, with less than half of respondents engaging with the algorithm or the didactic sessions (Figure 1). The most frequently reported barriers to PCT use included lack of knowledge about the test (65%, n=90) and perception of conflicting evidence for use (43%, n=60).There were 467 patients that were included in the post-implementation cohort treated with antibiotics for LRTI and/or sepsis who subsequently had a PCT ordered (Figure 2). Patients with two positive PCT results were 2.4 times more likely to have antibiotics prescribed than those with two negative PCT results (p = 0.02). Of these patients who had PCT testing performed, 54% did not have a second PCT test ordered as recommended by guidelines.

Conclusions: Despite an educational campaign and embedded clinical decision support algorithm in PCT order sets, physicians at our medical center did not routinely use PCT and still expressed some discomfort in interpretation for sepsis and LRTI. Additionally, many did not follow the institutional algorithm. However, among patients who did have PCT testing, testing was associated with decreased antibiotic exposure in an unadjusted analysis. Developing creative methods to expand clinician comfort with utilization and interpretation of PCT may have beneficial effects on antibiotic stewardship.