Case Presentation: Microangiopathic hemolytic anemia (MAHA) refers to mechanical hemolytic anemia characterized by schistocytes on peripheral smear (PS). It is seen in various conditions such as thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP), hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS), disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), infections and immune disorders. Rarely, it can occur in malignant tumors as a paraneoplastic syndrome. We describe a case of cancer related – MAHA (CR-MAHA). Through this case, we emphasize the importance of diagnosis and management guided by a thorough history and physical examination to minimize diagnostic delays and errors.

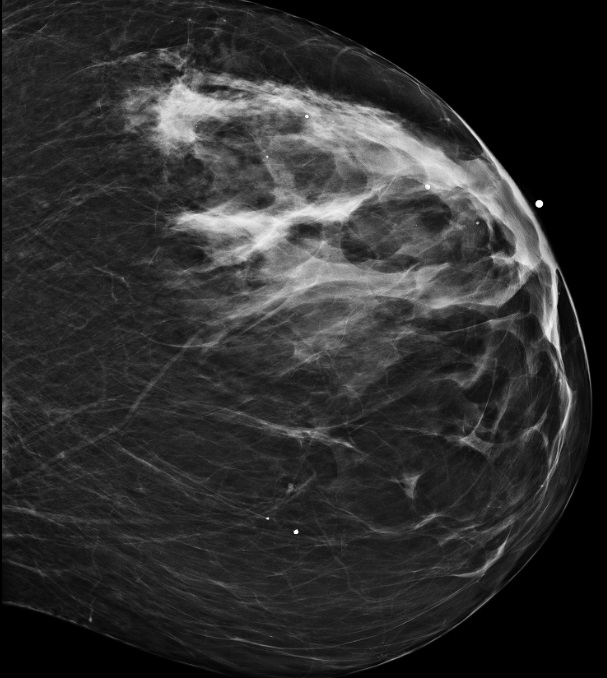

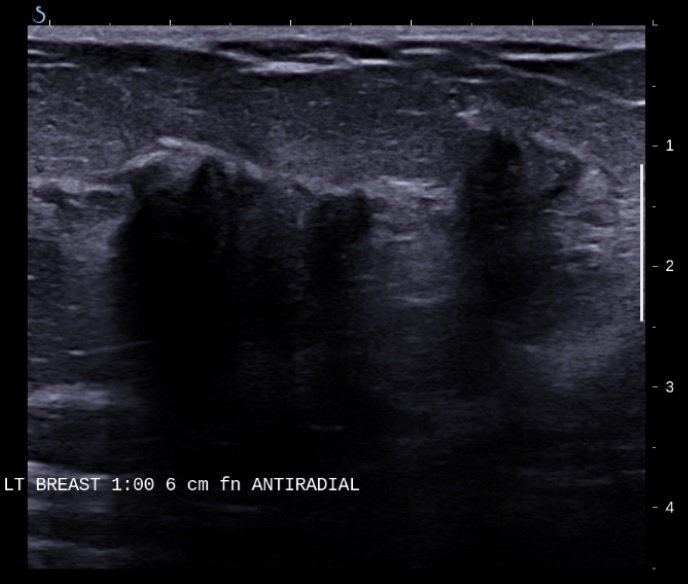

Discussion: A 63 yrs. old woman presented with complaints of progressive fatigue for two weeks. Admission labs were significant for severe anemia and thrombocytopenia requiring transfusions. Work up revealed Coomb’s negative hemolytic anemia with many schistocytes on PS. She received urgent treatment for presumed TTP with three sessions of plasmapheresis. Remaining laboratory work up including coagulation profile, fibrinogen, urinalysis, blood and urine cultures, C3, C4, serum and urine protein electrophoresis, Anti-nuclear antibody (ANA), Anti-Neutrophil cytoplasmic Antibody (ANCA), Extractable Nuclear Antigen Antibodies (ENA) panel, Shiga toxin and ADAMTS 13 level were normal. Given persistently low platelets, she received three sessions of Intravenous Immunoglobulins (IVIG) for suspected Immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) and was discharged on prednisone with weekly Rituximab infusions. Two weeks after discharge she was re-admitted with abdominal pain. CT Abdomen/pelvis showed multiple lytic lesions of pelvis and vertebrae concerning for Multiple Myeloma. Given persistent transfusion dependence, treatment with prednisone and rituximab was continued and a bone marrow biopsy was planned as outpatient. A week after discharge she was admitted to our MICU with life-threatening epistaxis and severe thrombocytopenia. Clinical examination was remarkable for a large, hard, left upper quadrant breast mass. Laboratory work up was consistent with Coomb’s negative MAHA. Autoimmune panel was unremarkable. Fine needle aspiration and biopsy revealed invasive ductal carcinoma of breast. Bone marrow biopsy revealed sclerotic marrow with metastatic adenocarcinoma consistent with primary malignancy of breast. Treatment with letrozole and palbociclib was initiated with improvement in transfusion requirements.

Conclusions: CR-MAHA is associated with a poor prognosis. In patients with an abrupt onset of MAHA and thrombocytopenia, a diagnosis of thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) and empiric treatment with plasma exchange is usually sought. CR-MAHA is often included in such cases. Plasma exchange is seldom effective in CR-MAHA as it is believed to have a different pathogenic mechanism to HUS or TTP. However, it often responds to treatment of the underlying malignancy. In today’s practice, technologies are often the first diagnostic tool. Physical examination inadequacies are a preventable source of medical error and a significant contributor to missed or delayed diagnosis. In our patient, a complete physical examination would have prevented significant morbidity, unnecessary treatment and delay in diagnosis. This case underscores the need to emphasize the importance of physical examination in medical education and practice as a patient safety strategy.