Case Presentation: We report a case of vancomycin-induced DRESS (Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms) syndrome in a 48-year-old female presenting 6 days after discontinuation of IV vancomycin for the treatment of MRSA bacteremia secondary to right foot cellulitis. She presented with 2 days of painful, diffuse, blanchable, morbiliform rash with palmar petechiae. The rash spared the mucosa and did not involve the full-thickness of the dermis. She also had associated lymphadenopathy and leukocytosis with eosinophilia of 6320 cells/uL. An infectious cause was determined unlikely with negative urinalysis, chest x-ray, syphilis assay, blood culture, mycobacterial and viral panel. Her liver function tests and kidney function were within normal range. She was evaluated by dermatology, who determined her RegiSCAR (European Registry of Severe Cutaneous Adverse Reactions to Drugs and Collection of Biologic Samples) score to be 4, thus a diagnosis of DRESS was “probable” and a review of her prior medications identified vancomycin as the only potential culprit. She was started on oral prednisone with prolonged 6 week taper and provided topical triamcinolone and hydrocortisone. There was improvement of symptoms by hospital day 3 and discharge from the hospital on day 5.

Discussion: DRESS syndrome is a rare but life-threatening illness with a mortality rate between 10-20%. Visceral involvement is the primary cause of morbidity with the most commonly implicated organs being the liver (80%) and kidney (28%). DRESS syndrome has been most commonly reported with anti-convulsants, with phenytoin, carbamzepine and lamotrigine being among the most reported causes. Other commonly reported drugs include allopurinol, penicillin and cotrimoxazole. DRESS is not a commonly known side effect of vancomycin. The earliest reported cases of vancomycin-induced DRESS syndrome occurred in 2005.

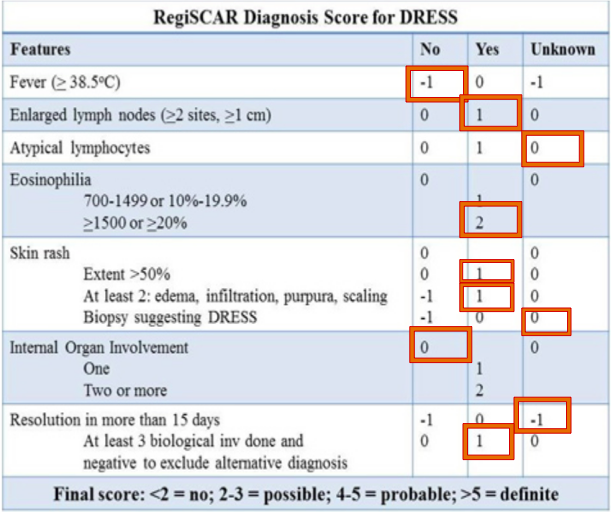

Due to their overlapping symptoms, DRESS syndrome can be difficult to distinguish from Stevens-Johnson Syndrome, Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis, Hypereosinophilic Syndrome and viral exanthems. Therefore, the RegiSCAR scale (Figure) was constructed to retrospectively help clinicians evaluate the likelihood of DRESS. The scale helps predict the diagnosis of DRESS syndrome as being “no”, “possible”, “probable”, or “definite”.

The case presented a diagnostic challenge because the patient developed the syndrome after already discontinuing the causal drug. However, the patient’s RegiSCAR score made the diagnosis “probably” upon arrival. This helped quickly classify the syndrome so that treatment could be provided. Treatment of DRESS most importantly involves discontinuing the offending agent and supportive care. Use of glucocorticoids has not been proven to improve outcomes but remains a common practice.

Conclusions: This case demonstrates a rare but life-threatening effect of vancomycin exposure.

DRESS is a rare but severe reaction featuring a diffuse, cutaneous rash, fever, lymphadenopathy, eosinophilia and systemic organ involvement. It has been most often reported with anticonvulsant medications and develops 2 to 8 weeks after drug exposure, but shares overlapping symptoms with other cutaneous drug reactions, making its diagnosis difficult, especially when the offending agent is not commonly associated with DRESS syndrome.

Clinicians should have a high index of suspicion and the use of the RegiSCAR scale can help expedite the diagnosis and treatment of DRESS syndrome.