Background: Many institutions struggle with educational structure in the wake of ACGME duty hour restrictions, and concerns have been raised that there has been a net negative impact on quality of education. Efforts to balance service and education are continuously in flux.

At our institution efforts to address this balance have included a redesign of inpatient services . The current system utilizes a 6 day cycle in which teams take a large bolus of patients on 3 days and potential overflow on the other 3 days, unless restricted by their cap.

We hypothesize that patients were less likely to be discharged during days on which lowering a team’s census increased the likelihood of receiving new patients. We further hypothesized that this delay in discharge would prolong length of stay (LOS) for patients present on service on these pre-call days

Methods: We examined team census, admissions, discharges, and average length of stay for a 120 day period from December 2014 through February 2015. We then compared average number of patients discharged per patient on the census for each day in the call cycle to determine if there were variations which might reflect a discharge bias. Following this, we extrapolated the different discharge rates to determine how that might affect LOS for the average patient on the teaching services on those days.

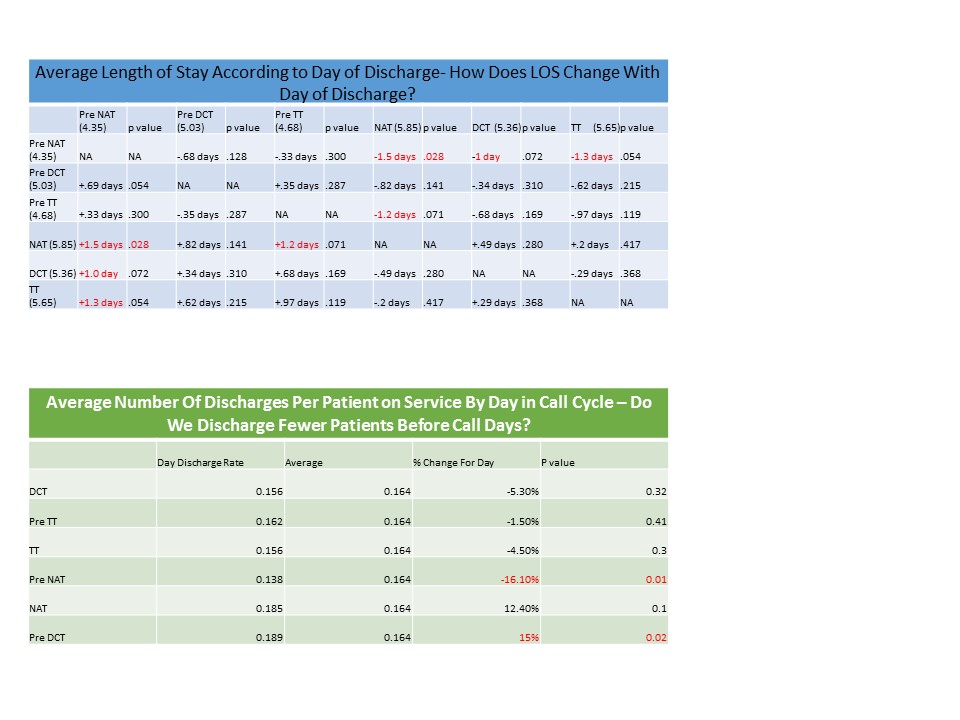

Results: When discharge numbers were evaluated on a per capita basis, variations coinciding with the call cycle were found. On average, there were .16 discharges per patient on census, across all days of the call cycle. The number of discharges on the Pre Night Accept Teams (pNAT) were significantly less (by 16%) than on any other day, followed by a present but non-significant increase in discharges for the following two days (12% and 15%, respectively). Other days in the cycle fell well within expected variations of discharge patterns.

Length of stay was significantly longer for patients discharged on the NAT (5.85 days) and significantly shorter for patients discharged on the day on which the team is pNAT (4.34 days). Other fell within the statistically expected variation of length of stay. See table 1 charts for details.

Conclusions: There were significantly fewer discharges on the pNAT day than any other day in the call cycle. This coincided with a significantly longer LOS for patients discharged the following day (NAT). Assuming all other patient characteristic were similar there appears to be a call cycle based bias in the choices made by the discharging physicians. We do not propose that this data identifies a specific reason behind that bias. Since NAT is the busiest day in the cycle it is plausible to suggest that providers employ more exacting criteria for discharges when on the pNAT as a way to spread the workload and avoid being overwhelmed.

The current model for taking patients onto the Internal Medicine services was designed to address a perceived service/education imbalance as well as work hour limitations. However there appears to be an unintended consequence of increasing the length of stay. This inefficiency is most evident when there is a large bolus of admissions to a single team, a model common to many teaching services, and identifies a target which should be considered as hospitals struggle to maximize the use of their limited resources.