Case Presentation:

A 51-year-old male with a history of recent pneumonia and cocaine use (most recently 4 weeks prior) presented to the emergency department for shortness of breath. Exam demonstrated decreased left sided breath sounds with x-ray confirming left lower lobe consolidation and effusion. Labs revealed neutropenia and a negative urine drug screen. Neutropenia was attributed to use of cocaine contaminated with levamisole, due to a similar findings one year prior, and treated with filgrastim. By hospital day (HD) five, neutropenia and pleural effusion had nearly resolved.

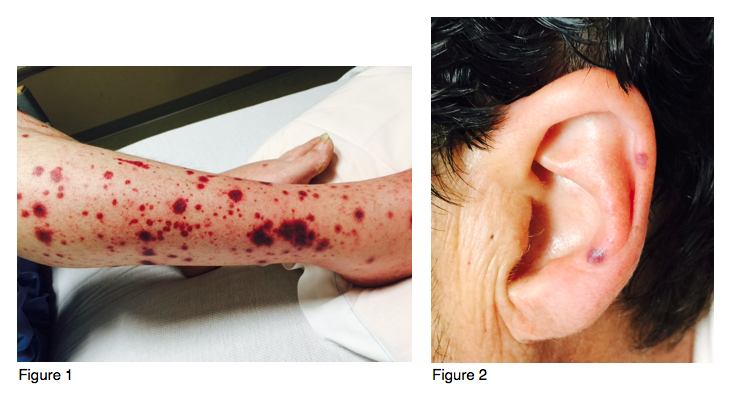

On HD six, the patient developed painful, purpuric skin nodules with central darkening on his ankles progressive to his bilateral legs, upper extremities, and ears. Testing yielded negative results for blood cultures, hepatitis B and C, HIV, RPR, anti-nuclear antibodies, and rheumatoid factor. Septic emboli and cryoglobulinemia were thought to be less likely due to normal echocardiogram and negative cryoglobulins. Rheumatology recommended checking anti-nuclear cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA), myeloperoxidase antibody (MPO), proteinase 3 (PR3) and anti-phospholipid antibodies (APA) – all of which resulted positive except for pANCA. Skin biopsy revealed leukocytoclastic vasculitis.

The patient’s exam, labs, and biopsy were consistent with levamisole-induced vasculitis. He was started on prednisone, with significant improvement of skin findings within 24 hours. He was discharged on a steroid taper with cocaine cessation counseling.

Discussion:

Levamisole was historically used as an anti-helminthic drug in veterinary medicine, and more recently as an immune-modulator in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Severe adverse effects including severe neutropenia, vasculitis, pulmonary, and renal dysfunction prompted withdrawal from medical use. It is now popularly used as a cocaine adulterant due both to its mood-enhancing properties as well as drug potentiation effect.

LIV most commonly begins as purpura, progressing to bullae then necrosis. The time of onset is usually within 24 hours of ingestion. Lesions commonly involve the lower extremities, however ear involvement is considered pathognomonic. Levamisole’s short half-life makes lab detection difficult. Labs are typically positive for ANCA, MPO, and PR3 antibodies, with variable APA results. Biopsies can range from no evidence of vasculitis (48%), thrombotic vasculitis (36%), to leukocytoclastic vasculitis (16%). Positive myeloperoxidate (MPO) and proteinase 3 (PR3) antibodies differentiate LIV from cocaine-induced vasculitis. Besides cessation of levamisole exposure and supportive care, limited literature supports benefit from systemic corticosteroids only in patients with leukocytoclastic vasculitis.

Conclusions:

Levamisole is a frequent additive to cocaine. Due to rising levamisole concentrations in cocaine and cumulative exposure, the incidence of levamisole-induced vasculitis (LIV) is increasing. Given the rising incidence, consideration of this diagnosis is essential to initiate appropriate diagnostic testing and treatment.