Background: Patient-centered communication has been associated with positive patient outcomes such as improved patient understanding and adherence to therapy. Teaching patient-centered care (PCC) and communication throughout a hospital stay, with an emphasis on understanding each patient’s perspective and circumstances, is a focus on one of four general inpatient medicine services at our hospital. We did not provide scripting or guidance on how to conduct bedside rounds, but we hypothesized that communication during rounds would be more patient-centered on the PCC team than on standard teams.

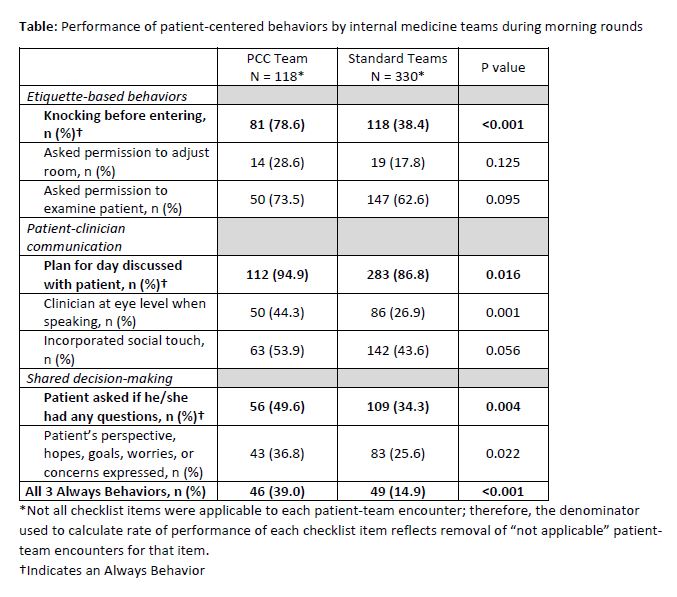

Methods: The setting for this cross sectional study was the inpatient general medicine teaching service of a 335-bed urban academic medical center. Based on literature review, expert consultation, piloting and refinement, we designed an observation checklist of 8 behaviors for inpatient bedside rounds covering domains of etiquette-based behaviors, patient-centered communication, and shared decision-making. Three items considered most essential to characterize patient-centered bedside rounds were designated Always Behaviors: knocking before entering, articulating the medical plan for the day, and asking if the patient had any questions. One study team member was trained in the use of the observation checklist. A second observer from the study team joined for a subset of the observations collected in the study in order to establish the level of inter-rater agreement.

Results: Between August 2018 and May 2019 a single observer completed 448 observations of patient-team interactions; 118 were of the PCC team, 330 of the 3 standard teams. Daily team census was not different between PCC team and standard teams (mean 10.0 vs. 10.2 patients, p=0.75). Performance of patient-centered behaviors are shown in the Table. All 3 Always Behaviors were performed in 39.0% vs. 14.9% of patient-team encounters on the PCC vs. standard teams (p<0.001). The location where the team presented clinical information and updates was at the bedside more frequently for the PCC team (28.0% vs. 10.9%, p<0.001). Mean time spent discussing each patient on rounds in any location, including hallway, team work room, bedside, or other location, was not different between PCC and standard teams (18.1 vs. 18.2 minutes, p=0.73). The subset of time spent at the bedside per patient was greater on the PCC team (8.5 vs. 7.1 minutes, p<0.001). The amount of time spent at the bedside when all 3 Always Behaviors were vs. were not performed was 8.3 vs 7.2 minutes, p=0.11. Absolute agreement on performance of checklist items ranged from 77 to 100% based on 48 encounters where the second observer collected data. The absolute agreement for performance of all 3 Always Behaviors was 97.9%, kappa 0.94.

Conclusions: Performance of the 3 Always Behaviors during inpatient team rounds was more frequent on a team with a PCC curriculum than on standard teaching teams. However, the performance rate was lower than anticipated. Data collected on patient-centeredness of bedside rounds will be useful for quality improvement of rounding communication patterns. The checklist may be of interest to medical educators and hospital leaders more broadly, to establish baseline patient-centeredness of patient-team interactions and to guide quality improvement efforts. Next steps will include assessment of patients’ perspectives on communication on rounds and evaluation for the degree of correlation with checklist observations.