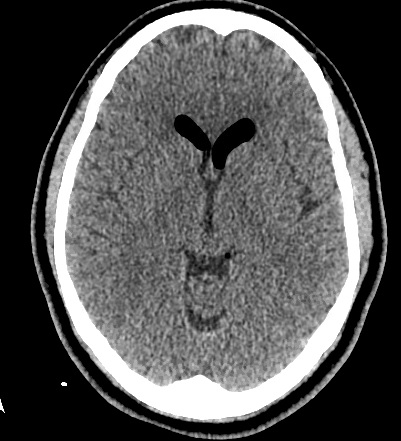

Case Presentation: A 27-year-old pregnant woman with no significant medical history presented to the hospital in labor and underwent spontaneous vaginal delivery. Shortly after epidural analgesia and delivery of her child, she started having a severe, shooting headache radiating from her back to her temporal and frontal regions. She reported that the headache was worse with changes in position; 5/10 intensity while lying down and 10/10 while sitting or standing up. Acetaminophen provided minimal relief. Vitals signs and neurological examination were normal. Neurology was consulted; a post-dural-puncture headache (PDPH) was suspected, and a computed tomography (CT) scan of the head was obtained prior to an epidural blood patch (EBP). CT revealed pneumocephalus (PNC) within the intraventricular and subarachnoid compartments. The patient was treated with ibuprofen, bed rest, and oxygen therapy delivered via a 100% non-rebreather mask. She received an empirical EBP on postpartum day 1 due to lack of resolution and the orthostatic nature of her headache. The headache resolved by postpartum day 2, and she was discharged home safely.

Discussion: Epidural injections are commonly utilized for pain management and in obstetrics. Post-dural-puncture headache is the most common adverse effect of spinal punctures. The mechanism of the headache is believed to be due to intracranial hypotension leading to a positional headache. Nonetheless, a rare complication of epidural anesthesia is pneumocephalus, in which air is trapped intracranially. Classically, pneumocephalus in analgesia occurs as a result of inadvertent injection of air into the dural space. This occurs if the dura is traversed during using a syringe and feeling for loss of resistance while injecting air or saline to confirm proper placement into the epidural space. Furthermore, significant CSF leak during puncture can create negative pressure and lead to formation of PNC. Though often asymptomatic, the development of a pneumocephalus can consequently result in an acute, rapid-onset, severe headache within seconds to minutes. On the contrary, PDPH usually develops in a matter of hours to days and is worse with sitting or standing; improves with lying down. CT is regarded as the gold standard for detection of PNC given its ability to detect small amounts of air. As little as 2 cc of air intracranially can be sufficient to translate into symptoms.Pneumocephalus is typically reabsorbed spontaneously within days to weeks; 85% of cases by 2-3 weeks. Treatment primarily consists of symptomatic management, bed rest, and refraining from Valsalva maneuvers or coughing and sneezing that can aggravate the headache. Furthermore, data suggests that normobaric oxygenation with high FiO2 may result in a faster resolution of PNC and its symptoms. The postulation is that augmenting oxygenation leads to washout of pulmonary nitrogen and the creation of a gradient that allows diffusion of nitrogen from the intracranial bubble into the bloodstream. In the rare event of tension PNC, in which pressure effect with neurological deterioration occurs, surgical decompression may be necessary. Unlike PDPH, epidural blood patch has no role in treatment of PNC.

Conclusions: Pneumocephalus is a rare and serious complication that must be considered by physicians during their evaluation of headaches after spinal injections. CT imaging is the modality of choice for diagnosis. Albeit spontaneously resolving in most cases, PNC must be monitored for any evidence of neurological compromise.