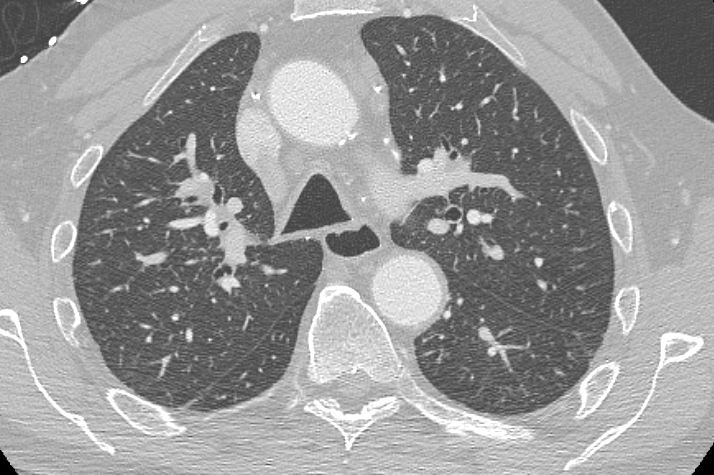

Case Presentation: A 76 year old male with a history of hypertension and hyperlipidemia presented with acute onset ascending weakness, perioral tingling, and loss of temperature sensation. The patient’s profound weakness progressed over the course of a few days, with subsequent diplopia, hallucinations, and confusion. He received the influenza vaccine a few weeks prior, and traveled to Paris and Wyoming within the last six months. Review of systems was positive for a chronic, intermittent cough and negative for all other infectious symptoms. Initial blood pressure was 159/94 mmHg. All other vitals were within normal limits. He was alert but could not answer questions appropriately. Neurological exam was notable for left sided facial droop, 4/5 strength in the right arm, 3/5 strength in the left arm, 2/5 strength in the hips and knees bilaterally, and hyporeflexia in all extremities. Initial labs were notable for elevated AST and ALT only. CSF analysis revealed a lymphocytic pleocytosis (WBC 41, protein >600, glucose 69). MRI head and spine and EEG were unrevealing.Initial differential diagnosis included Guillain-Barré syndrome, viral encephalitis, and autoimmune encephalitis. Acyclovir, vancomycin, ampicillin, and ceftriaxone were empirically started started and subsequently discontinued after infectious workup was unrevealing. Patient’s weakness progressed, though altered mentation improved and diplopia resolved. He developed symptomatic bradycardia along with rapid oscillations in blood pressure (80s/40s to 180s/90s mmHg), along with an AKI secondary to urinary retention. Neurology was consulted, who recommended empiric IVIG therapy for suspected Guillain-Barré syndrome or autoimmune encephalitis. After a five day course of IVIG, the patient demonstrated a modest improvement in strength. Considering unrevealing work up, a CT chest was performed to evaluate for occult malignancy out of concern for paraneoplastic syndrome. To our surprise, it revealed hilar lymphadenopathy which then directed our suspicion towards a rare diagnosis of neurosarcoidosis (Figure 1). He underwent biopsy of lymph nodes via endobronchial ultrasound, but biopsy results were nondiagnostic. Serum ACE was normal. Given the high clinical suspicion for neurosarcoidosis, high dose steroids were started with subsequent improvement in strength, sensation, and mentation.

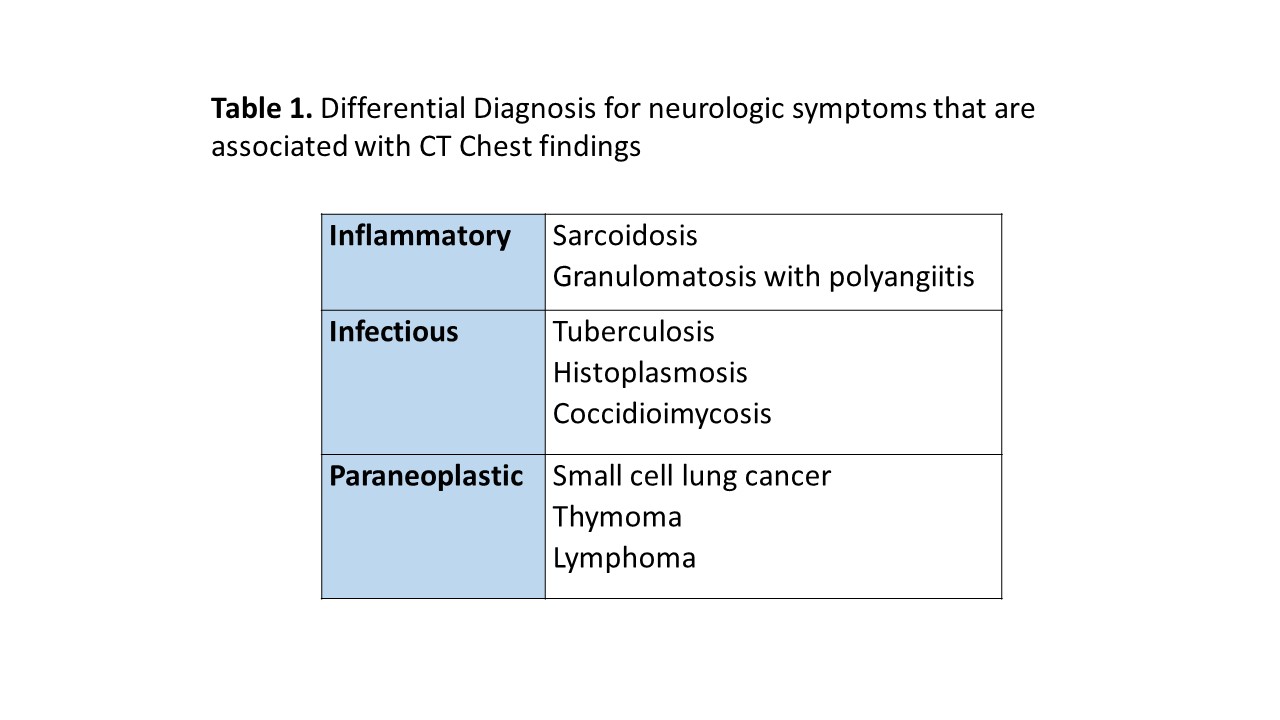

Discussion: Neurosarcoidosis occurs in 10-15% of patients with sarcoidosis, and can be difficult to diagnose. Patients present with a variety of neurological symptoms including peripheral neuropathies, encephalopathy, cranial neuropathies, and dysautonomia with changes in heart rate and blood pressure. MRI brain can reveal meningeal or parenchymal enhancement, but is only present in 40% of cases. CSF studies show a lymphocytic pleocytosis and elevated total protein. Biopsy is not necessary to confirm diagnosis. Corticosteroids are the mainstay of treatment.This case highlights the utility of Chest CT when evaluating patients who present with an unusual constellation of neurologic symptoms and a negative infectious workup. Various pulmonary and mediastinal findings are associated with neurologic disease (Figure 1), and can guide further workup.

Conclusions: Neurosarcoidosis is a rare cause of encephalopathy, weakness, and other neurologic symptoms. Consider a CT chest if preliminary work up with MRI, lumbar puncture, EEG, and infectious studies are unrevealing.