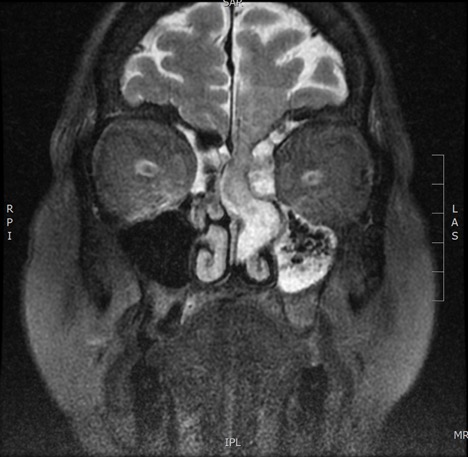

Case Presentation: A 62-year-old female with a past medical history of stroke, obesity, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia presented to the emergency department with fever and altered mental status. She was started on empiric meningitis treatment and her mentation improved dramatically with eventual return to baseline. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) studies from a lumbar puncture performed later during her admission were consistent with partially treated bacterial meningitis. Of note, the patient had copious clear, left-sided rhinorrhea during this procedure. A CT of the head was obtained which demonstrated a mixed-density mass in her left nasal cavity concerning for tumor versus encephalocele. MRI confirmed a 1.8 cm by 0.5 cm by 2.9 cm encephalocele extending through a 5 mm defect in the left cribriform plate into the left nasal fossa (Image 1). ENT and neurosurgery were consulted, and the patient underwent successful anterior fossa defect and encephalocele repairs. The patient later reported that she had a four-year history of intermittent headaches associated with clear rhinorrhea from her left naris which was exacerbated by leaning forward. She denied any history of head trauma or cranial surgery.

Discussion: Encephaloceles and cerebrospinal fluid leaks may result from congenital, traumatic, neoplastic, or spontaneous causes. Patients often describe constant or intermittent clear rhinorrhea with salty or metallic taste which may be associated with headache. Spontaneous cerebrospinal fluid leaks are most commonly associated with defects in the cribriform plate, and are often found in obese, middle-aged females (1), as in our patient. Though the exact incidence of encephalocele is unknown, the rising incidence of obesity and obstructive sleep apnea with associated increased intracranial pressure has led to a rise in number of cases of encephaloceles and spontaneous CSF fistulas. It is hypothesized that chronically increased intracranial pressure may contribute to localized thinning of the bone with eventual herniation of meninges (2). The presence of CSF rhinorrhea indicates an open communication to the intracranial space, placing patients at risk for meningitis and other cerebral complications and thus necessitating treatment in most cases. Physicians should be aware of CSF leaks and have high suspicion for them, especially when rhinorrhea is unilateral, exacerbated by leaning forward, and/or associated with headaches, as prompt recognition and treatment can help prevent dire complications.

Conclusions: Here we describe a case of encephalocele with CSF leak complicated by bacterial meningitis. To prevent such life-threatening complications, identification and repair of encephaloceles and leaks is vital. Physicians should maintain a high degree of clinical suspicion, and pursue further imaging, nasal endoscopy, and lab testing when indicated. A history should be obtained for prior sinus or cranial surgery, head trauma, congenital abnormalities, episodes of meningitis, and presence of obesity.