Background: Hospitalists routinely precept third year medical students on general internal medicine wards. One of the key patient care tasks for students is to interpret and initiate management for common electrolyte abnormalities. Formal training to achieve this is lacking for students transitioning from preclinical to clinical years. We designed and implemented a module on interpreting and initiating management for electrolyte abnormalities during our transitioning to clerkship course for incoming 3rd year medical students.

Methods: This 50-minute session was co-developed and led by a 4th year medical fourth-year medical student who had recently completed clerkship rotations supervised by a hospitalist clinician-educator. Kern’s six steps of curriculum development were followed to develop the educational objectives and evaluate the session. Students were asked to take 5 minutes to reflect and write down what they knew about causes and management of the 5 commonly encountered electrolyte abnormalities on inpatient wards: hypokalemia, hyperkalemia, hypomagnesemia, hypophosphatemia, and hypocalcemia. We used the primacy-recency effect framework to frame our session. This effect postulates that students best retain information presented at the beginning (prime-time 1) and end (prime-time 2) of a session, while the middle portion (down-time) is best suited to practicing information delivered during prime-time 1. During the first part of the session (prime-time 1), we presented the causes and management of the five electrolyte abnormalities. For downtime, five clinical vignettes were then presented to students, each representing a potential scenario of electrolyte abnormalities seen during the clerkship. The session concluded with a summary of important points and Q&A. A handout was provided to students with summary points that could be readily used on rounds. Given the virtual nature of the curriculum in the setting of the COVID-19 pandemic, small group sessions were conducted virtually. A total of 199 students were divided into 5 small groups to attend the session. Students completed a pre- and post-session survey and knowledge test that measured both comfort level and medical knowledge in interpreting and initiating management of common electrolyte abnormalities.

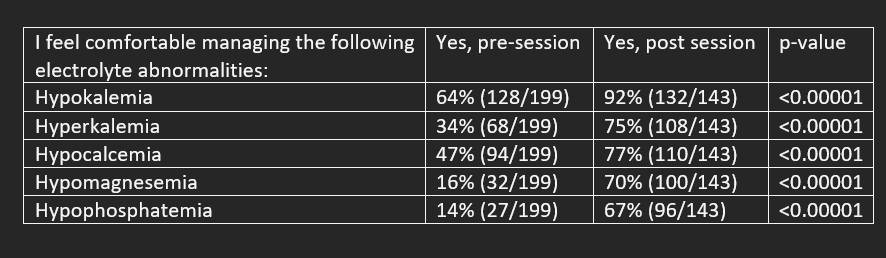

Results: 199 students completed the pre-session survey, and 143 students completed the post-session survey. When comparing post-session to pre-session surveys, there was a significant increase in comfort level managing electrolyte abnormalities (Table 1). On a 5-point Likert scale (1 being “excellent” and 5 being “do not repeat”), the module was rated at a value of 1.67, indicating a high level of participant satisfaction (N=143). The proportion of correct responses on the knowledge test increased from 42% (500/1194) before the session to 69% (591/858) after the session (p < 0.0001).

Conclusions: A medical student and hospitalist co-led module based on sound educational principles significantly improved medical student knowledge and comfort level in managing commonly encountered electrolyte abnormalities on inpatient floors. Since much of the third year of medical school is spent in the inpatient setting, hospitalists skilled in educational theory and curriculum development are well suited to lead the development of course content for rising third year medical students.