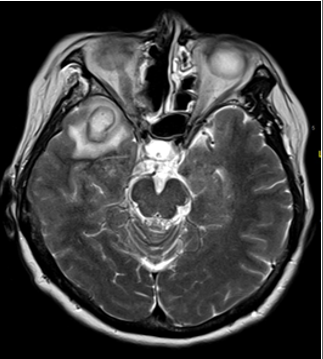

Case Presentation: A 55-year-old female with a past medical history of stage IV intranasal mucosal melanoma (status post resection of the nasopharynx, medial maxilla, floor of the sphenoid sinus, and clivus – two years prior) and current use of nivolumab presented to the hospital with two weeks of a worsening, pressure-like right temporal headache and one week of a persistent cough and sore throat. She had tried doxycycline from her PCP for possible sinusitis, but only her facial pressure improved while her other symptoms persisted. On presentation, she was afebrile and had stable vital signs. Physical exam was significant for right hemifacial numbness and right lower facial weakness. Labs revealed a WBC of 13.39 k/uL (Reference range: 4.0 – 10.9 k/uL) with 67.1% neutrophils. Blood cultures were negative. A CT head ruled out intracranial hemorrhage. An MRI brain identified a 2.0 x 1.7 cm ring-enhancing lesion on the right temporal lobe with restricted diffusion and hemosiderin deposition, initially misdiagnosed as a possible hemorrhagic and necrotic metastasis. She was started on dexamethasone and levetiracetam for seizure prophylaxis. Upon reevaluation of the MRI, the lesion was rediagnosed as a cerebral abscess. On hospital day 2, she was started on broad-spectrum antibiotics. On day 5, she underwent a right temporal craniotomy with aspiration of the abscess, which a culture later identified as containing Streptococcus intermedius. Her antibiotics were changed to IV penicillin G, of which she completed six weeks of continuous infusion before transitioning to oral penicillin V. Imaging at 1 month showed no residual abscess, and follow-up imaging at 7 months showed no reoccurrence. Her headache significantly improved, but she began to experience focal seizures with secondary generalizations. She was restarted on anti-epileptics and has remained seizure-free up to her last documented follow-up.

Discussion: Brain abscesses are rare in developed nations and can be difficult to recognize due to their similar presentations with other, more frequently seen brain lesions (e.g. metastases, cystic gliomas). It is vital to diagnose and treat brain abscesses early on, as delayed antimicrobial therapy can increase mortality risk by 50% per day. A persistent, progressive, and pressure-like headache is usually the main presenting symptom of a brain abscess. Focal neurologic signs can vary in both manifestation and severity depending on the specific location of the abscess. Patients often present without fever or changes in mental status, further masking the underlying infectious process. Risk factors for a brain abscess include immunosuppressive medications or diseases, bacteremia, and trauma or surgery of the head. CT imaging can help to initially identify the presence, size, and location of the mass, but MRI with diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) is more capable of identifying the lesion’s etiology. Neurosurgery with fluid aspiration is required for pathogen identification and can help to relieve intracranial pressure. Recommended management includes targeted antibiotic therapy for 6-8 weeks with follow-up imaging biweekly for at least three months.

Conclusions: Though rare, a brain abscess must always be considered in a patient with a worsening headache, especially with a history of immunosuppression or surgery near the brain. Early recognition and antibiotic administration are key to patient survival, as a delay in treatment by even one day can mean the difference between life and death.