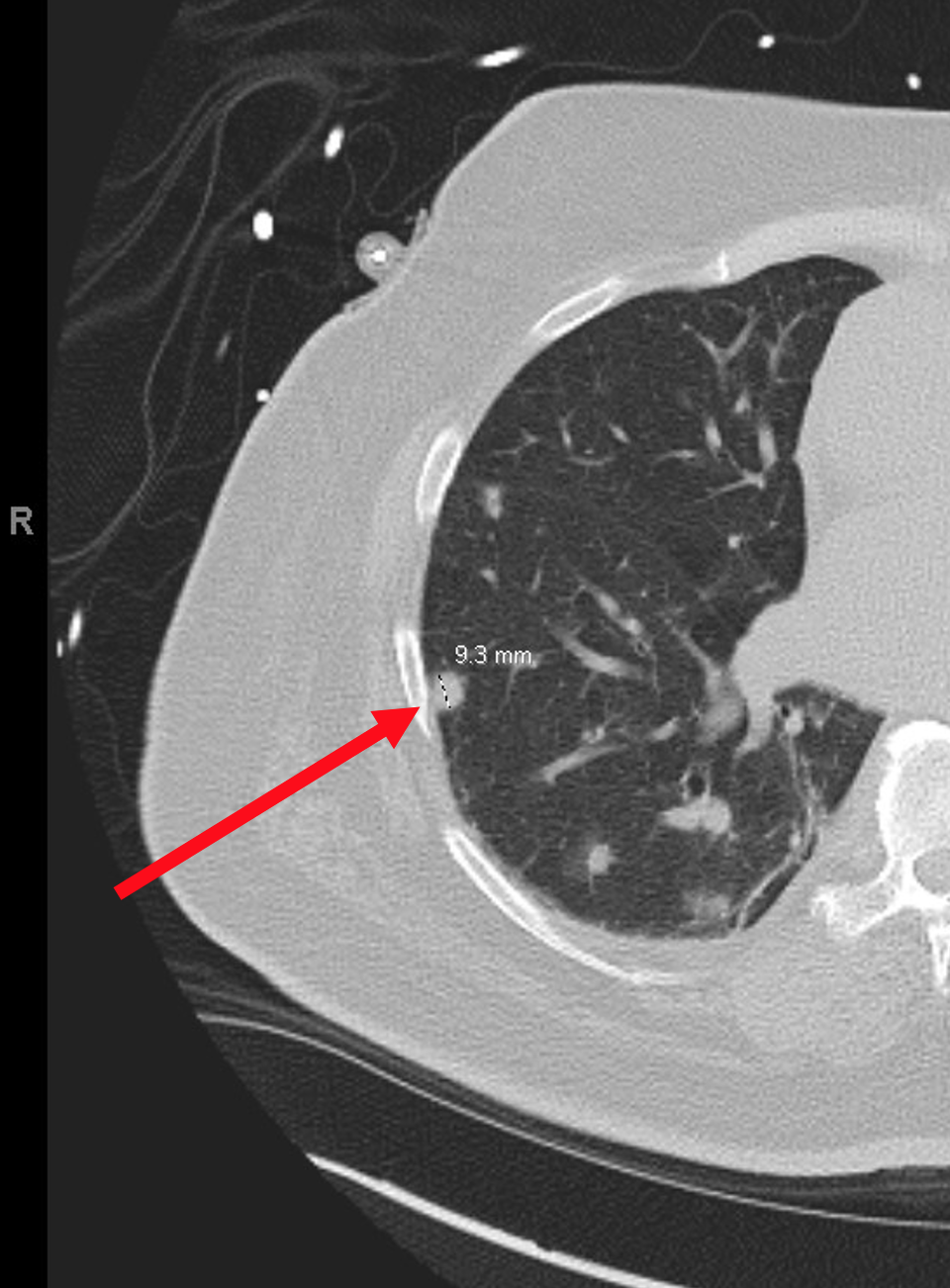

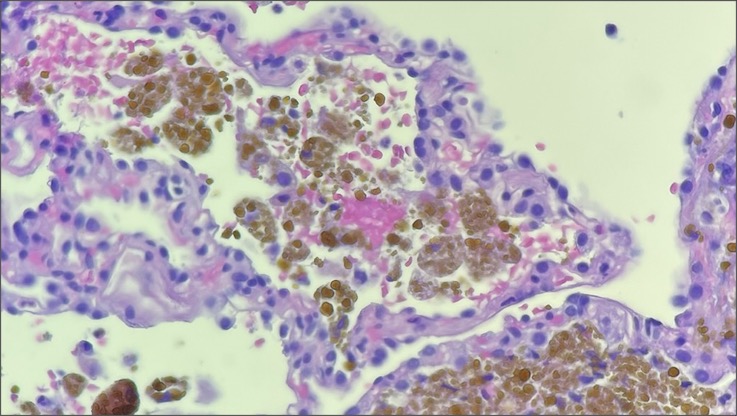

Case Presentation: The patient is a 59-year-old male with chronic heart failure found to have cardiac sarcoidosis and subsequently treated inpatient with high-dose steroids. In addition, computed tomography imaging revealed pulmonary nodules. Due to a suspected infection, empirical antibiotics and antifungals were administered, however, treatment failed to clear the nodules. Further, weeks of antibiotic therapy was complicated by candidemia, leading to additional morbidity. Biopsy was performed to narrow antibiotic selection and rule-out malignancy, but the results revealed hemosiderin-laden macrophages consistent with “heart failure cells”. A diagnosis of pulmonary edema was rendered.

Discussion: This case is unique in that infection was the prime suspect, yet the lung findings proved to be an idiosyncratic manifestation of cardiac insufficiency. Left-sided heart failure causes pulmonary vascular congestion which permits red blood cells to extravasate into alveolar spaces. Hemoglobin is then degraded into hemosiderin by alveolar macrophages transforming them into “heart failure cells”. Radiographically, cardiogenic pulmonary edema characteristically presents as venous, interstitial, and alveolar edema, cephalization of pulmonary veins, cardiomegaly, and pleural effusions. However, abrupt shift of fluid into alveoli can form a nodular pattern on imaging – so called “heart failure balls” – which is often not considered by clinicians in the work-up for pulmonary nodules. A case study from 2021 exhibited this phenomenon when diffuse pulmonary nodules were found on computed tomography imaging of a patient suffering from congestive heart failure. The patient showed no signs of infection, yet a lung biopsy was scheduled to rule-out infection, malignancy, and inflammation. However, after two weeks of diuresis, imaging showed complete resolution and the unnecessary biopsy was cancelled. Fortunately, antibiotics were never initiated. In a similar case study from 2011, a patient with congestive heart failure also demonstrated multiple pulmonary nodules surrounded by ground glass opacities (“halo sign”) on imaging along with a right-sided pleural effusion. Bronchoalveolar lavage was performed to rule-out infection, however antibiotics were not administered due to low suspicion. After one week of diuresis, the nodules and unilateral pleural effusion were cleared. These case studies support adding heart failure to the differential when faced with a patient presenting with diffuse pulmonary nodules. This will help clinicians avoid superfluous procedures and therapeutics, ultimately optimizing patient recovery and cost-effectiveness.

Conclusions: This case illustrates the significance of recognizing heart failure as a potential culprit for pulmonary nodules. Once considered, trialing diuresis with repeat imaging could completely resolve the pathology, therefore supporting heart failure as the likely cause. This would avoid invasive procedures and unnecessary therapies which would allow for more value-based care and avoidance of complications like opportunistic infections.