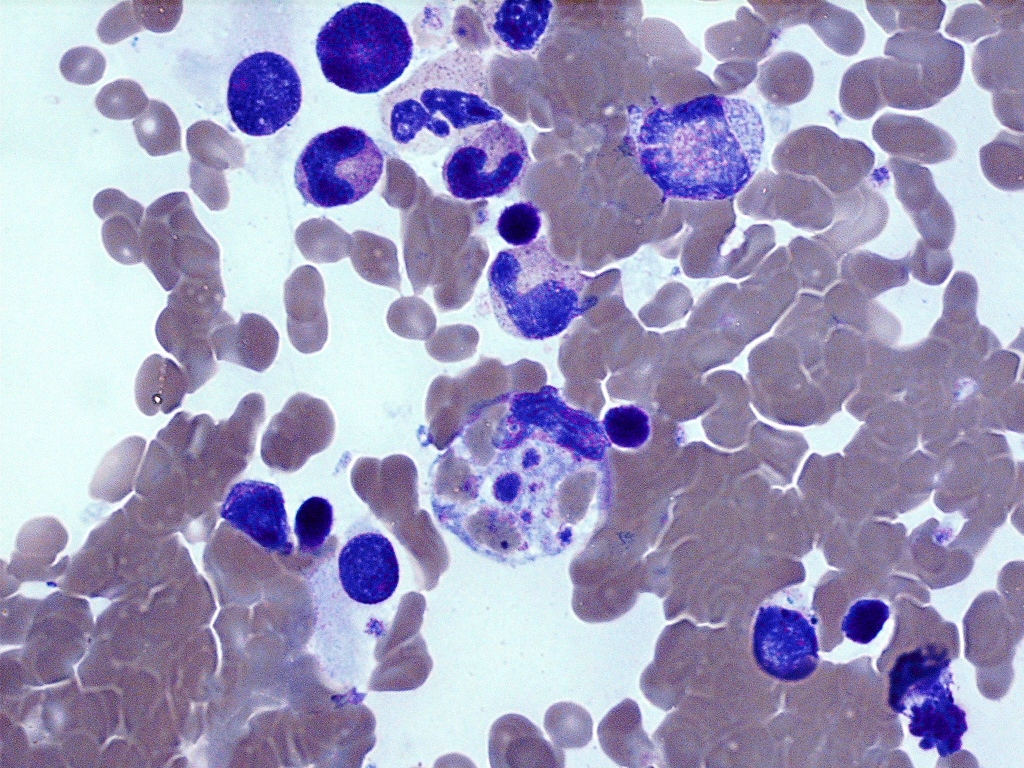

Case Presentation: A 39-year-old previously healthy woman presented to the hospital with worsening fever, arthralgia, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea after discovering a tick bite two weeks prior. She was diagnosed outpatient with Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (RMSF) ten days before hospital presentation and was prescribed doxycycline, although she missed most doses due to emesis. On arrival, her temperature was 101°F, heart rate 119 bpm, and blood pressure 80/48mmHg. She was ill-appearing and encephalopathic. She had no nuchal rigidity, jaundice, lymphadenopathy, murmur, hepatosplenomegaly, swollen joints, or rash.White blood cell count was 0.77 k/uL, platelets 49 k/uL, hemoglobin 12.3 g/dL. Creatinine was 1.74mg/dL, AST 318 U/L, ALT 87 U/L and the remainder of liver function tests including INR were normal. Her ferritin was 19,426 ng/mL. EBV IgM and RMSF IgG were positive. Infectious workup was otherwise negative including urinalysis, respiratory and gastrointestinal panel, HIV, CMV, Lyme, Anaplasma, Babesia, and Ehrlichia. CXR, CT and MRI head, CT abdomen and pelvis, and echocardiogram were also unremarkable for infectious sources.She was in shock and given her hemodynamic instability, elevated ferritin, and bi-cytopenia in the setting of acute tick-borne and viral illness, hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) was considered. Interleukin-2 receptors were elevated at 1311 pg/mL. With fever, bi-cytopenia, elevated IL-2 receptors, and hyperferritinemia, she met 4/8 HLH criteria. Empiric treatment was started with dexamethasone, etoposide, and IV doxycycline. Bone marrow biopsy later revealed a hypocellular bone marrow with occasional hemophagocytic histiocytes, confirming HLH. She clinically improved and was discharged home.

Discussion: HLH can be clinically indistinguishable from septic shock and multi-organ failure due to non-specific clinical and laboratory findings. The diagnosis is made using the Histiocyte Society’s criteria. Of the criteria, hyperferritinemia >10,000 ug/L has a 90% sensitivity and 96% specificity for HLH. In populations with culture-negative septic shock, a ferritin level should be considered. Extreme ferritin elevations (i.e. >10,000 ug/L) should prompt further evaluation for HLH.Infections cause half of the cases and are most commonly viral, including Human Immunodeficiency Virus, Epstein Barr Virus, Cytomegalovirus, Human Herpes Virus 6, and Parvovirus B19. Malignancies, usually hematologic, are the next most common trigger at 27%. It is important to identify the underlying HLH trigger to aid in treatment.

Conclusions: Acquired HLH is an under-recognized, life-threatening condition that is important for an internist to identify. HLH is often triggered by viral illnesses and should be suspected in culture-negative shock with cytopenia and hyperferritinemia. Of the Histiocyte Society’s diagnostic criteria, extreme hyperferritinemia has high sensitivity and specificity for diagnosis.