Background: Emergency Department (ED) boarders create both hospital flow and clinical care challenges (1). ED boarders are isolated from medical teams based on hospital wards, which can impair coordination between physicians and ED based interprofessional staff (nursing, case management, social work, pharmacy and bed management) and lead to worsened operational and clinical outcomes. As ED boarders are generally assigned rooms in order of bed-request, patients who have been in the ED for 12 – 24+ hours awaiting a bed often reach a floor only to be discharged within a few hours. Patients admitted to units with limited beds, such as step-down or progressive care units (PCU), can create a patient flow bottleneck.

Purpose: We piloted a hospital medicine (HM) physician led multidisciplinary team for ED-boarded patients with the goals of improving ED and hospital throughput as well as our patients’ clinical care. We aimed to identify ED boarding patients who could be discharged directly from the ED, to coordinate transition of care resources, to drive forward clinical care and to triage boarded patients to appropriate units when unable to discharge from the ED.

Description: Parkland Memorial Hospital (PMH), the urban academic safety net hospital for Dallas County, has the busiest ED in the United States with 242,640 ED visits and 59,736 admissions in 2018 (2). Our HM program has an average daily census of 300 patients on its direct care service covered by 20 daytime physicians. The 55 patients admitted per day are seen by 5 physician and 4 advanced practice provider admitters and coordinated by 3 physician “triagists” covering day, evening and night shifts. The PMH ED typically boards 10-15 HM patients daily. A single HM physician was assigned to be the primary provider for 10-14 patients boarding in the emergency department. On days of surge demand, based on a pre-defined threshold of ED boarders, census, and overnight admissions, a second HM physician would be called in to target ED boarders as well. Patients identified as potential quick discharges by HM admitters overnight were preferentially assigned to the HM-ED physician(s). Each HM ED based physician would lead a multidisciplinary team comprised of social workers, care mangers, bed management representatives, pharmacists, and charge nurses which met at 0900 daily to help expedite potential discharges, direct ancillary staff resources, review and update bed status (i.e. observation vs inpatient, ward vs step-down unit) and drive clinical care forward. Once patients reached the wards, if the patient were projected to be in the hospital for more than another 24 hours, they would be transferred to the appropriate, geographically based HM physician.

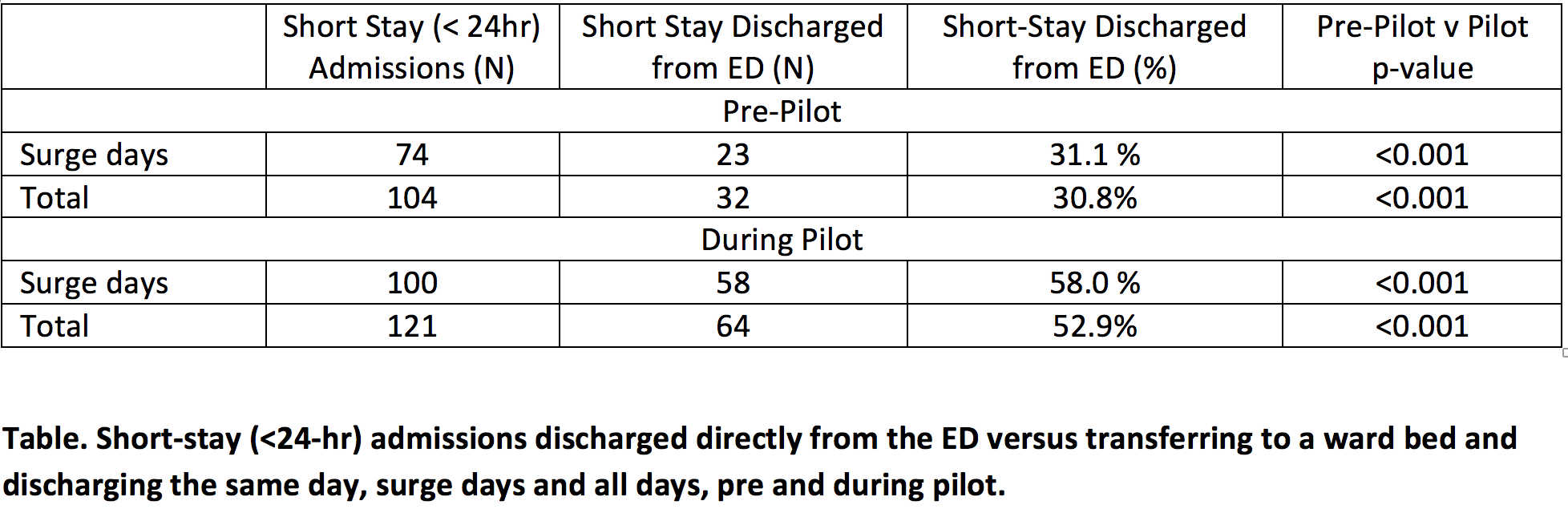

Conclusions: Our HM-ED multidisciplinary team surge response program increased discharges directly from the ED, was able to expedite clinical care and identify patients initially requiring PCU beds who were then suitable for general floor beds. Accordingly, on surge days, the percentage of ED boarders discharged directly from the ED nearly doubled, patients admitted under PCU status were more likely to be down-graded to floor status and ED support staff, including social workers, care coordinators, physical therapists, pharmacists and financial counselors efforts were better coordinated and leveraged (Table). The primary drawbacks to the system included provider strain from a high-turnover service and an increase in hand-offs for patients not discharged from the ED.