Background: Respiratory failure is the most common organ failure syndrome in US hospitals (1). Hospitalists strive to detect the earliest signs of respiratory instability. Measurement of respiratory vital signs (like respiratory rate & oximetry) is a necessary aspect of risk stratification, but it is not sufficient. In one study, 46% of hospitalized patients had no significant vital sign change in the 24 hours before an unplanned intubation (2). Therefore, hospitalists must also monitor for physical diagnostic signs that link the appearance of breaths to respiratory instability. Many pathognomonic patterns of high-risk labored breathing have been described. For example, when rib-dominant breaths alternate with abdomen-dominant ones, the patient is said to exhibit “respiratory alternans,” a sign of inspiratory muscle overload (3). However, the manual assessment of such signs lacks sensitivity, inter-rater reliability, and scalability (4). We sought to (a) identify technologies that can measure labored breathing and (b) assess their readiness for clinical adoption by hospitalists.

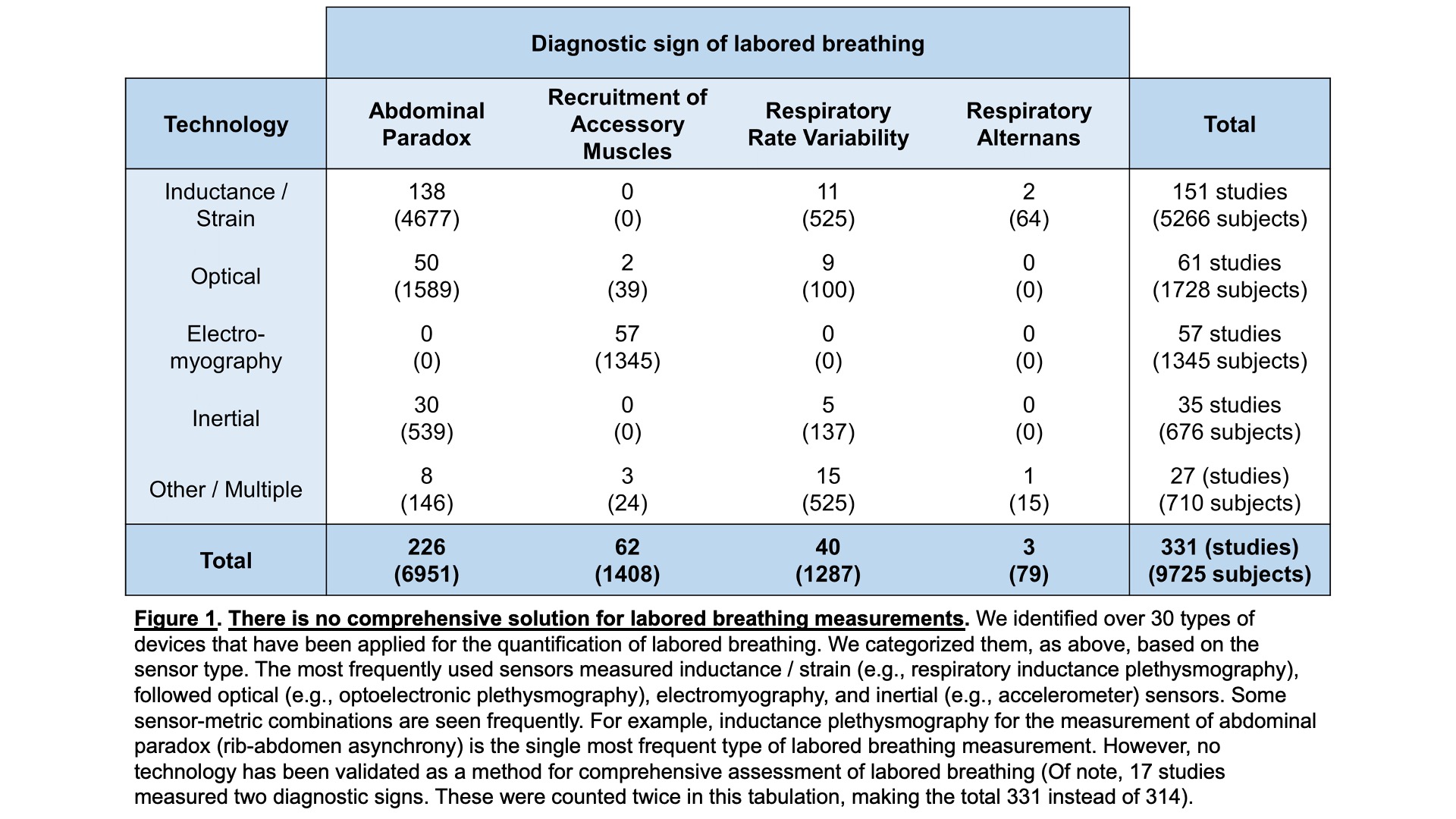

Methods: We selected 4 well-established diagnostic signs of labored breathing: (1) respiratory rate variability, (2) recruitment of accessory muscles (upper-rib elevation by the scalene and sternocleidomastoid muscles), (3) abdominal paradox (rib-abdomen asynchrony), and (4) respiratory alternans (described above). We systematically searched PubMed using pre-specified keywords corresponding to these four signs. We identified 2868 abstracts. Two reviewers independently screened each abstract to ensure that it reported on technology that quantified the diagnostic signs of interest. A third reviewer resolved any disagreements. We excluded 2423 articles with an abstract review and included 445 articles for full paper review. We excluded an additional 127 articles after full paper review, and we were unable to acquire 4 articles. We included the remaining 314 articles for analysis.

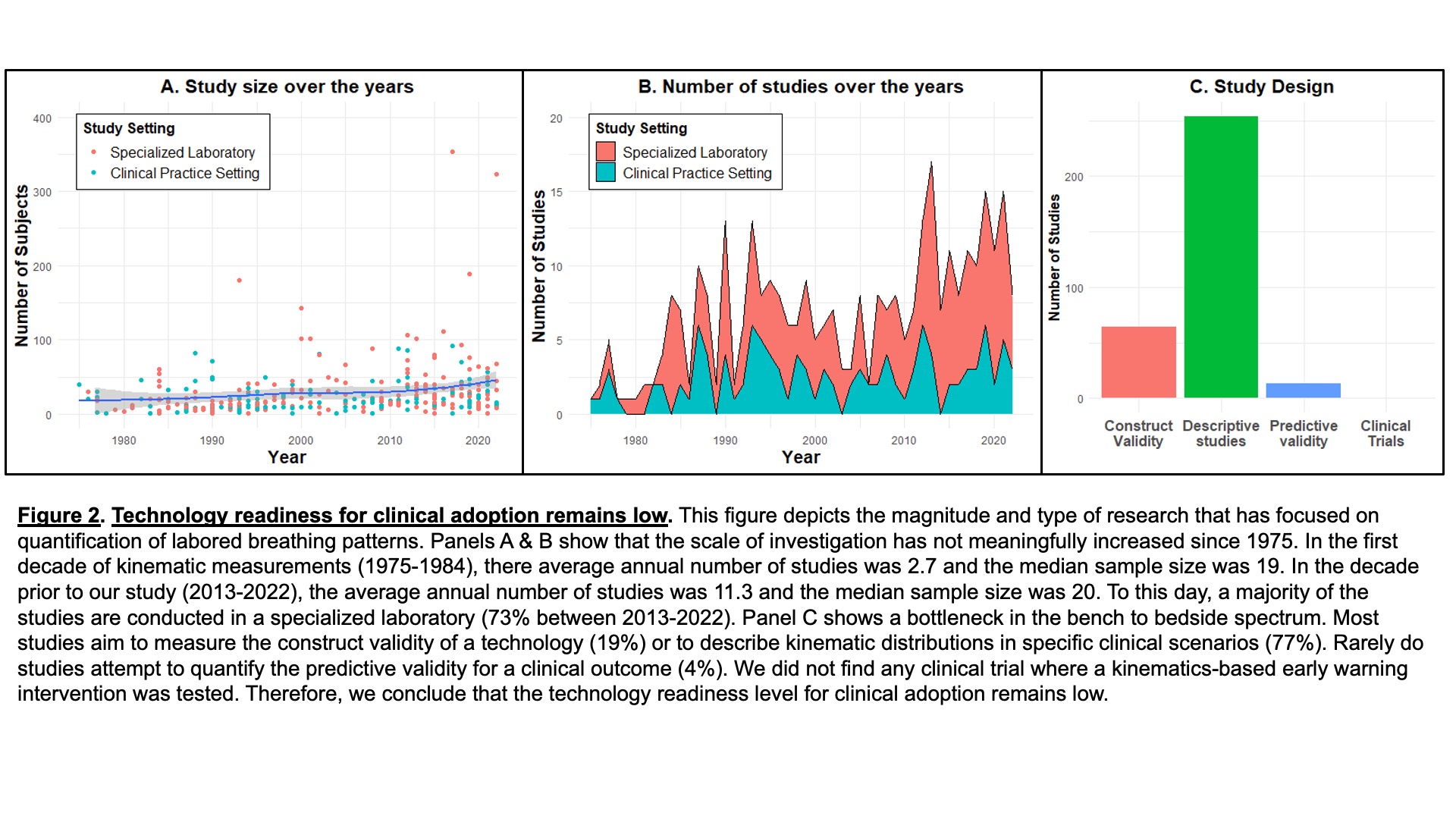

Results: Quantification of labored breathing has been attempted for over 50 years; the earliest study included in our analysis was published in 1975. Over 30 different hardware configurations have been tried, either alone or in combination. However, none of them have been validated as a comprehensive solution to measure all the four diagnostic signs that we studied (details in Figure 1). Despite enormous improvements in sensor technologies and computing capacity, the number and size of studies quantifying labored breathing has not increased meaningfully (Figure 2A, 2B). Most studies were conducted in specialized laboratories (63%) rather than clinical practice settings (37%). Most studies were designed to achieve early-stage validation (construct validity: 19%; descriptive studies: 77%; details in Figure 2C). The overall technology readiness level for clinical adoption remains low.

Conclusions: Labored breathing patterns contain vital prognostic information. They report on a dimension of pathophysiology that is not captured by conventional physiomarkers (5). This study describes an actionable bottleneck in the translation of bedside diagnostic signs of labored breathing into measurable physiomarkers of respiratory instability. Hospitalists are among the foremost stakeholders in solving this critical gap in contemporary respiratory monitoring; they can address this problem individually (collaborating with engineers) and collectively (publishing a notice of interest and/or advocating for dedicated research funding).