Background: Shared decision making is a key component of patient-centered care, allowing physicians and patients to balance the capabilities of the medical system with the values of the patient. However, the concept of shared decision making is not unique to a physician-patient relationship. Institutions from Athens, Greece to Silicon Valley have recognized the benefits of engaging individual creativity and thought to optimize group functioning and outcomes. At the same time, the traditional culture of academic medicine has a greater resemblance to military hierarchy than civilian democracy. Successfully applied, the democratization of decision-making increases the effectiveness and responsiveness of an organization while improving engagement and satisfaction of citizens at all levels.

Purpose: We sought to create a shared governance model to improve the quality of our large academic hospital medicine practice as evidenced by increasing physician engagement, satisfaction, productivity and professional development.

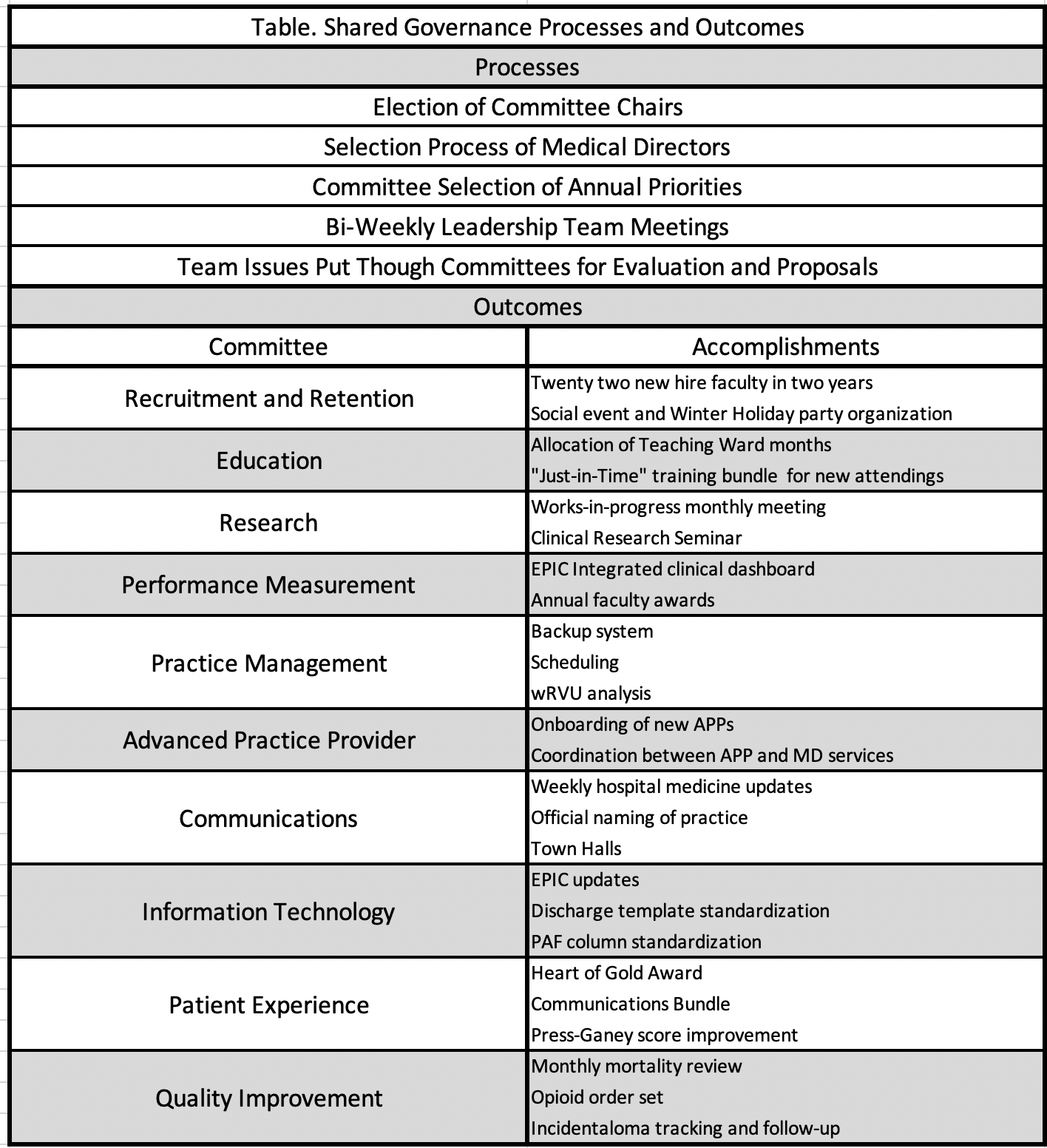

Description: Our academic hospital medicine practice of approximately 70 physicians underwent an administrative restructuring in 2018 to incorporate shared-governance principles. We created 9 initial committees (which later became 10) modeled after the Society of Hospital Medicine committees (Figure). Physicians are all required to join one committee based upon interest and are limited to no more than two committees. Each committee has a chairperson who serves a 2-year term.Each of the 10 committee chairs are guided by 1 of 4 medical directors. The 4 medical directors are guided by the division chief. The 4 medical directors, the director of the administrative team and the division chief form the “leadership team.” The leadership team conducts bi-weekly, 2- hour, meetings to review operational, clinical, academic and personnel issues.Committee members elect their own chairpersons. Likewise, each of the medical directors was elected democratically, with all faculty, committee chairs, and the leadership team having a weighted vote in the selection. Committees are given a high level of autonomy to select annual goals and projects. As the basic unit of self-governance, administrative issues affecting the group at large (i.e. scheduling, performance metrics, resource allocation) are first discussed in relevant committees which gives input to and/or develops proposals and/or solutions. Chairs discuss their committee’s input with the appropriate medical director who brings it to the leadership team for refinement and implementation.

Conclusions: Our shared governance has allowed us to engage faculty in decisions that reflect the group’s values, yet allows input and guidance from senior faculty and administration. Not only are we able to better harness the collective intelligence of our faculty, but more faculty have opportunities for leadership and to develop non-clinical domains of expertise. While there have been growing pains associated with the implementation, with some decisions and proposals either slow to evolve or meeting headwinds (ie. having to go through multiple iterations of the back-up system to get it dialed in), faculty retention, performance at all annually evaluated metrics and academic productivity have all seen gains well exceeding expectations. In 2020, we aim to continue to develop our shared governance model with quarterly town halls and the creation of a “speaker of the committees” role (1 of the 10 committee chairs) who will join the leadership team.