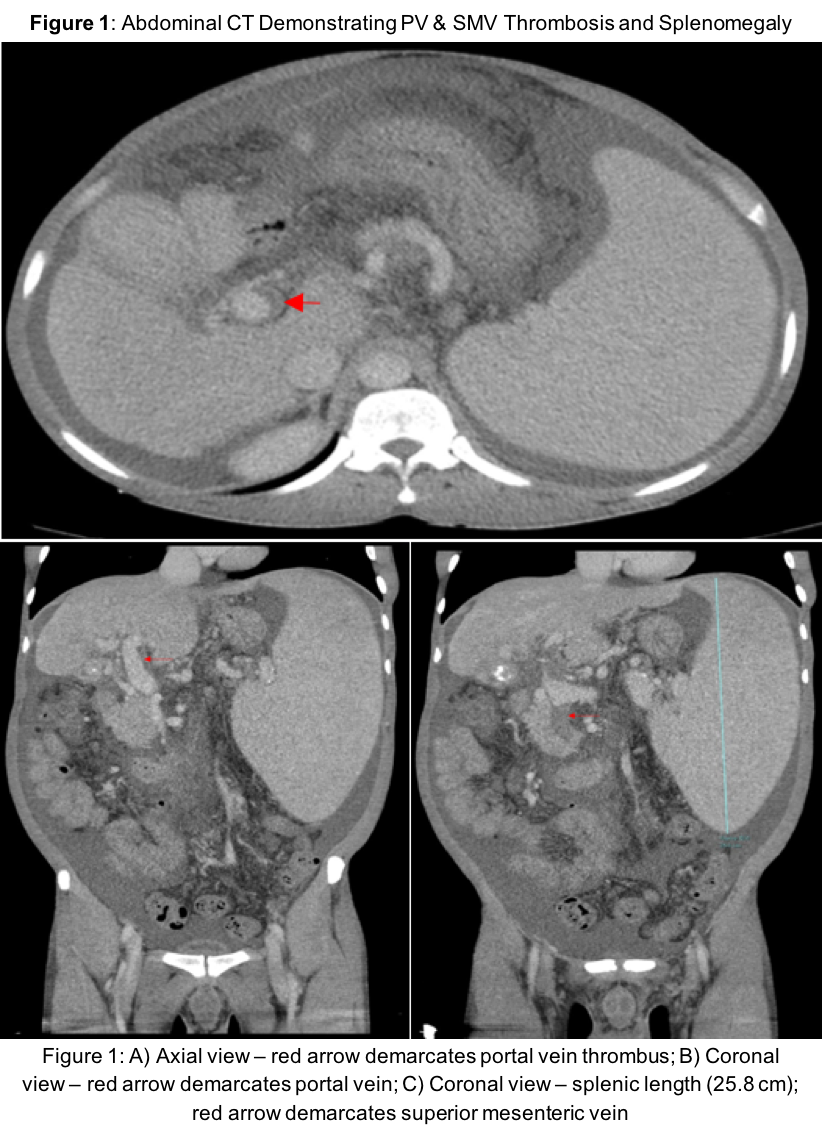

Case Presentation: A 39-year-old Zimbabwean male with a past medical history of hepatic schistosomiasis complicated by cirrhosis and pancytopenia presented to the ED with 7 days of abdominal pain and generalized weakness. The patient exhibited similar symptoms 8 months prior and had taken furosemide and spironolactone ever since, with no other home medications. Physical exam showed a distended abdomen with positive fluid wave, palpable spleen tip 2 cm proximal to the umbilicus (from 2 o’clock position), and an audible splenic bruit. Labs revealed marked pancytopenia: WBC 1.72 k/uL; hemoglobin (Hb) 3.2 g/dL (baseline 6-7); Plt 26 k/uL (baseline 70-90). LFTs were notable for INR 1.55 but were otherwise normal. Abdominal CT showed a non-occlusive thrombus in the portal and superior mesenteric veins to the level of the portal confluence. Persistent pancytopenia prompted a bone marrow biopsy to rule out a primary hematological etiology but was not tolerated. Three units of packed red blood cells were transfused, increasing Hb from 3.4 to 4.9 g/dL with no biochemical evidence of GI bleed, suggesting splenic sequestration as the etiology.Consult services deemed definitive treatments too risky, thus management was symptomatically focused. As spontaneous bacterial peritonitis was not suspected, we increased doses of home meds without antibiotics. Ascites was relieved, Hb returned to baseline, and the patient was discharged on adjusted diuretics and lactulose prophylaxis. Outpatient coagulation monitoring was arranged with a plan to reassess risks of definitive treatments as trends improved.

Discussion: Shistosoma mansoni is a parasite affecting 400,000 people in the US [1]. It releases eggs into the small bowel, which become entrapped in the pre-sinusoidal periportal space; induce inflammation and damage to hepatic cells; and lead to increased portal flow resistance and sequestration of RBC, WBC, and platelets. This case presents a man with recurrent episodes of pancytopenia secondary to liver insult but with no clear intervention that could safely treat the source of his condition.Splenic resection and partial embolization of the splenic artery are two definitive treatments for this problem. Resection would eliminate the body’s shunting mechanism. However, the surgical consult felt splenic resection was risky given the patient’s INR and platelet status. Partial splenic artery embolization would truncate circulation to this same machinery while maintaining the ability to fight off encapsulated microorganisms [2]. However, the hepatology consult was concerned given the procedure’s risks of potentiating associated sequelae of thromboses.

Conclusions: Patients with advanced liver schistosomiasis often present with hematologic pathologies secondary to splenomegaly. Physicians should consider splenic sequestration as a differential for pancytopenia and should be aware of available definitive therapies and their risks.