Background: The COVID-19 crisis has put an unprecedented strain on the US healthcare system (1). Hospital Medicine (HM) has been on the front lines of the crisis response (2). Multiple surges and troughs are expected before the pandemic subsides with a very large surge predicted for the winter of 2020-2021 (3). As the HM service of an 882-bed, urban academic safety-net hospital, we were asked to create a surge response system to absorb an additional 350 patients. The immediate response from the institution was to divert 3 teaching services from HM to non-HM faculty to increase HM’s capacity to provide care to COVID-19 patients. Our team places high value on our limited teaching opportunities and the loss of these teaching opportunities would be detrimental to the long-term mental health of our team.

Purpose: We sought to create a surge response system that would avoid the loss of our teaching opportunities and reflected our values of teamwork and equity.

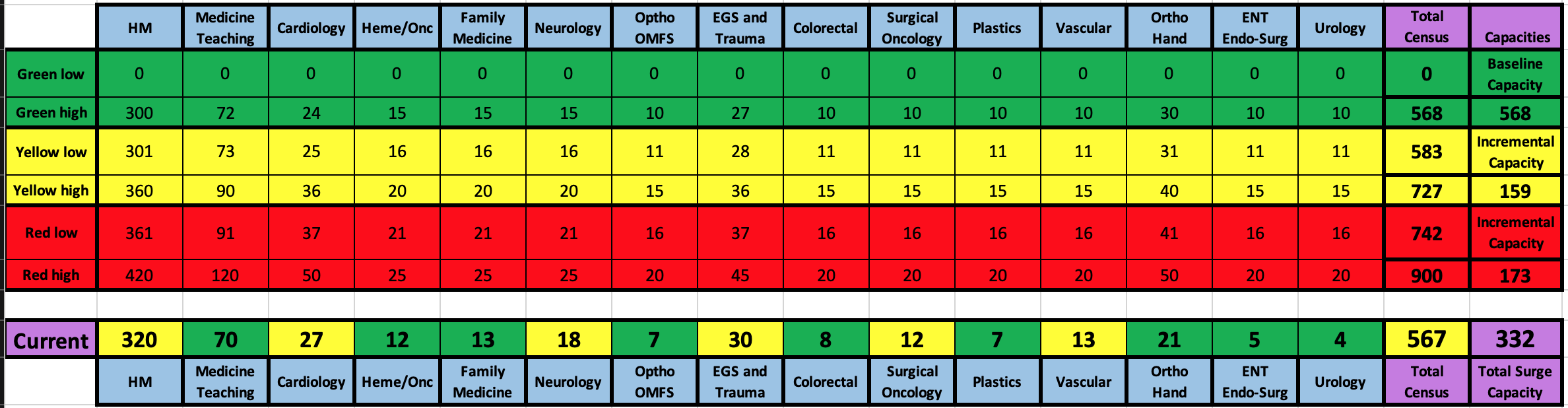

Description: We created a series of surge response levers that utilized the capacities of internal HM, department of internal medicine (IM), and non-IM. Service chiefs were asked to identify census levels for their respective teams that were comfortable (green), uncomfortable but sustainable for 2-3 months (yellow), and very uncomfortable but feasible for 2-3 weeks (red). These levels were used to develop a staffing capacity dashboard (Table 1). Surgical services, IM subspecialty services—such as cardiology and hematology-oncology—and family medicine agreed to increase capacity by increasing their censuses and offloading HM teams. General surgery would serve as primary on patients with pancreatitis, cholecystitis and partial small bowel obstruction; urology would admit patients with nephrolithiasis, pyelonephritis, and renal failure; and orthopedics and vascular surgery would admit patients with cellulitis and foot ulcers. Our medicine-pediatrics team had contingencies to divert their physicians from their pediatric rotation to adult rotations. Internal to HM operations, approaching our “red” zone, would trigger closing our consult service and reassigning faculty to an extra HM rounding service, reassign an underproductive evening admitter to rounding duties and reassign a daytime physician and advanced practice provider admitters to become rounders. In conjunction we would request teaching IM services to preferentially take early admissions. Our HM team also has a daily back-up rounder and the ability to schedule a second daily back-up rounder who would come in if the average HM rounding census exceeded a threshold. Finally, we trained a group of 11 IM (non-HM) volunteer faculty to care for COVID patients who could be activated to round.

Conclusions: This team approach led to an incremental “yellow” surge capacity of 159 patients and an additional “red” capacity of 173 patients for a total surge capacity of 332 patients. These contingencies increased the census from an upper green level of 568 patients to an upper red total of 900 patients. By 900 patients, non-physician resources such as beds and nursing staff would be primary capacity limiters. By creating a surge response system that prioritizes teamwork, we created a system that leverages the entirety of the medical staff. Equity in absorbing the COVID surge amongst all services allows our HM team to preserve limited teaching opportunities. Our approach has resulted in an unprecedented level of solidarity and camaraderie through the COVID crisis and should have a long-term positive impact on our HM team and medical staff.