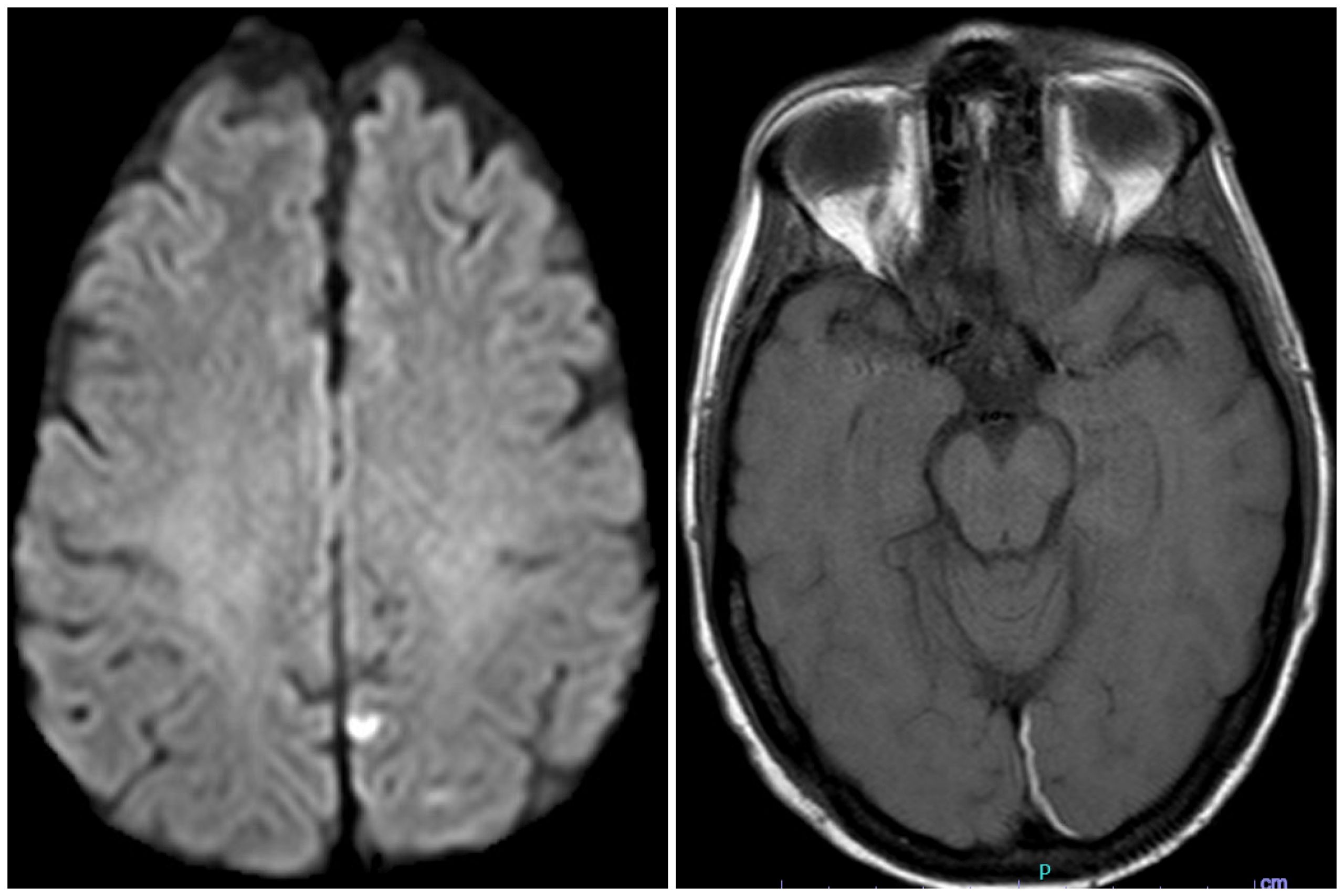

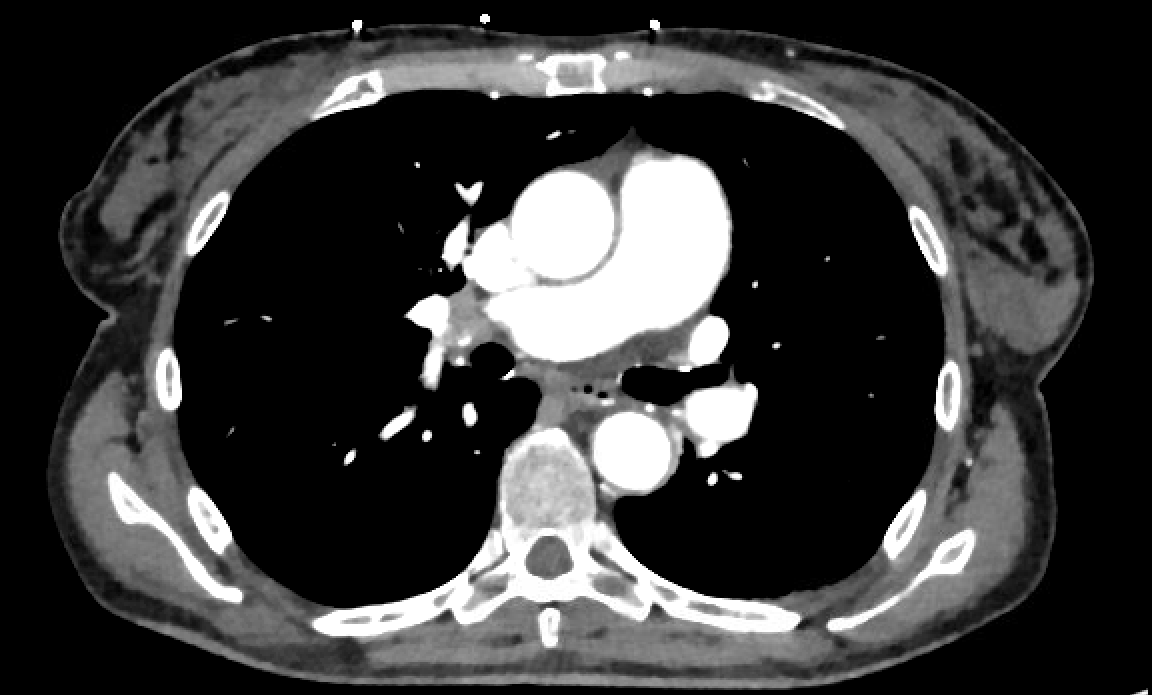

Case Presentation: A 65-year-old woman with antiphospholipid syndrome (APLS), and history of multiple lower extremity deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and miscarriages, on warfarin presented with syncope, fall, and head-strike. She was found to have an acute subdural hematoma (SDH) in the interhemispheric fissure and a non-occlusive DVT in the left femoral vein. Initial labs showed thrombocytopenia, coagulopathy, positive antinuclear antibody, and lupus anticoagulant (Table 1). MRI brain obtained days later also showed a small acute infarct in the paramedian left parietal lobe (Fig 1a-b). Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia was ruled out by a negative serotonin release assay (SRA). Given her clinical history in conjunction with giant platelets seen on peripheral smear, positive anti-platelet antibodies (glycoproteins Ia and IIa), and no identified alternative etiology of thrombocytopenia, a diagnosis of secondary immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) was made. She was subsequently treated with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) and dexamethasone. Romiplostim was added later for refractory thrombocytopenia though this did not significantly improve platelet count. Rituximab 375mg/m2 IV was given once. Platelet count increased rapidly from 55,000k/mm3 to 180,000k/mm3 in three days. It is unclear whether the rapidity of the response was due to rituximab or delayed effect from the three weekly doses of romiplostim.Initially, all forms of anticoagulation (AC) were discontinued due to severe thrombocytopenia with platelet count of 18,000k/mm3. Attempts to resume therapeutic heparin for DVT failed due to thrombocytopenia and blood loss anemia requiring multiple blood transfusions. Our patient was also not eligible for IVC filter placement because the diameter of the vein was too large. Eventually, she developed a mild tachycardia and CTA chest (Fig 2) diagnosed a segmental pulmonary embolism with transthoracic echocardiogram (Fig 3) showing McConnell’s sign and a patent foramen ovale. Hematology recommended low-dose apixaban while awaiting SRA results, dexamethasone, IVIG, and rituximab which improved platelet count enough to resume therapeutic AC with heparin. She was then bridged to warfarin and discharged home.

Discussion: It can be challenging to appropriately manage AC, either for prophylaxis or for therapeutic purposes, in patients with both strong indications for and contraindications against AC. In cases where there are contraindications for pharmacologic prophylaxis, such as thrombocytopenia, coagulopathy, or acute bleeding, it is recommended to hold AC. Shared decision-making with patients can help clinicians decide on an appropriate course of management in such complex clinical situations. In this case, the patient had strong risk factors for thrombosis given her previous diagnosis of APLS but had presented with an acute intracranial bleed after her fall. Given the acute SDH and development of ITP, she was not a candidate for AC for several weeks. It is possible that the PE could have been prevented had she been able to remain on warfarin.

Conclusions: Even in cases where there are clear contraindications for AC, it can be appropriate to use shared decision-making to guide further management. In this case, shared decision-making was used to resume AC after the patient was found to have a PE. Her case is unique as it highlights the complex decision-making with ITP associated with APLS which resulted in a very difficult balance between the risks of thrombosis versus bleeding with severe thrombocytopenia.