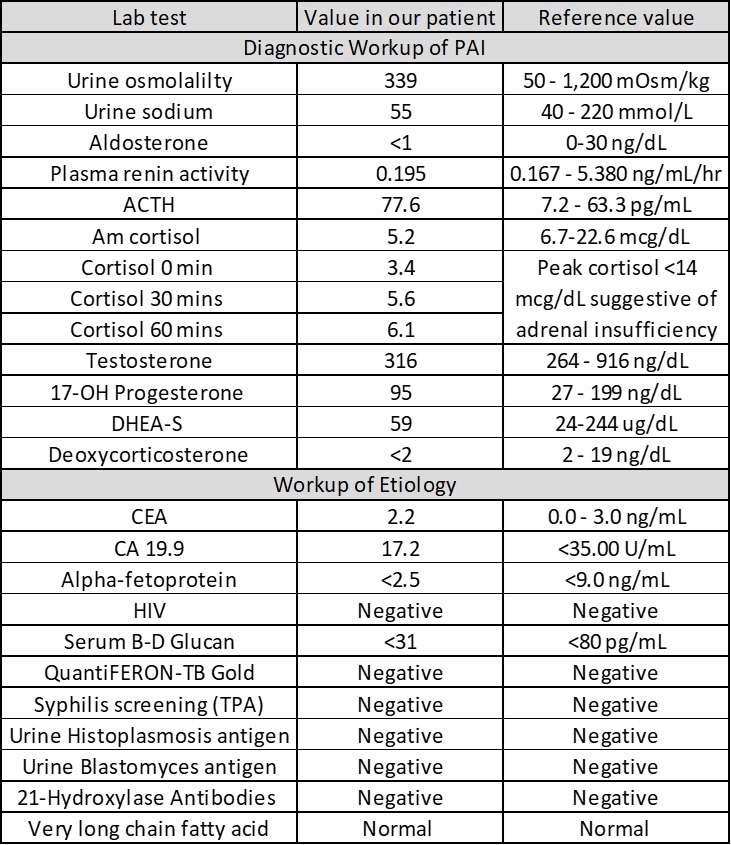

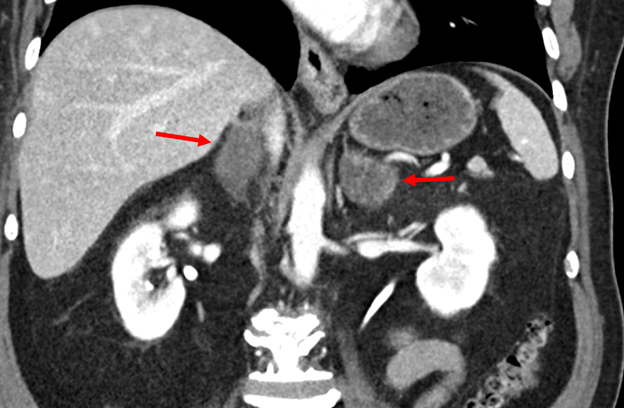

Case Presentation: A 66-year-old Hispanic male with a history of primary hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus presents to hospital with 3 months of progressive fatigue, poor appetite, watery diarrhea, dizziness, and vomiting. Vital signs were notable for postural hypotension (BP 146/84 sitting, BP 118/72 standing). Physical examination was normal with no skin or mucous membrane hyperpigmentation. Initial laboratory workup was notable for the following: hemoglobin 12.6 g/dL, white cell count 7 x 109 cells/L (11% eosinophils), sodium 118 mmol/L, potassium 4.8 mmol/L, creatinine 1.1 mg/dL, urea nitrogen 20 mg/dL, serum glucose of 99mg/dL, serum osmolality 257 mOsm/kg H2O, TSH of 1.45 uIU/mL, hemoglobin A1C 9.8%. With the patient’s hyponatremia with relative eosinophilia, adrenal insufficiency was suspected. Further workup was suggestive of primary adrenal insufficiency (table 1), which was supported by CT imaging revealing bilateral adrenal gland enlargement (figure 1). The patient was started on hydrocortisone and fludrocortisone with prompt improvement of his symptoms and normalization of serum sodium. A PET/CT scan showed increased uptake in his adrenal glands and hilar/mediastinal region. Adrenal biopsy revealed adrenal tissue necrosis and yeasts with thick-walled capsules, consistent with cryptococcus adrenalitis, which was confirmed with a high serum cryptococcus antigen titer of 1:160. CSF testing for cryptococcus antigen was negative. The patient was treated for disseminated cryptococcosis. No complications were noted on a 5-month follow-up visit.

Discussion: Primary adrenal insufficiency (PAI), also known as Addison’s disease, refers to the inadequate production of adrenal hormones due to a disease process that directly affects the adrenal glands. Causes include autoimmune adrenalitis, medication-induced adrenal suppression, infection, or infiltrative disorders. As with other causes of adrenal insufficiency, the presentation can be insidious and nonspecific. In the western world, PAI is typically seen in the context of an autoimmune process, whereas infectious causes like tuberculosis tend to predominate in low-income countries. Disseminated cryptococcal infection typically affects the lungs and central nervous system in immunocompromised hosts, such as patients with HIV. This case is peculiar in that our patient lacked typical risk factors apart from diabetes. It highlights a unique diagnostic challenge in hospital medicine and underscores the importance of broadening the differential workup in the setting of uncommon presentations while managing the underlying disease process.Apart from replacing deficient glucocorticoids (and mineralocorticoids if indicated), treatment of PAI from cryptococcal adrenalitis involves induction therapy with amphotericin B and flucytosine followed by prolonged therapy with fluconazole.The recurrence rate of cryptococcal adrenalitis in immunocompetent hosts remains uncertain due to the paucity of cases in literature. Although prolonged antimicrobial therapy may reverse gland enlargement in cryptococcal adrenalitis, it is unclear if recovery of adrenal function can sometimes be seen, as has been documented with other causes of infectious adrenalitis.

Conclusions: This case demonstrates that cryptococcus adrenalitis is a rare, albeit important consideration of PAI even in immunocompetent hosts, especially when initial workup is negative. The prognosis and recurrence risk remain areas of ongoing investigation.