Background: Sepsis is one of the most common life-threatening conditions and is associated with significant mortality, length of stay, and cost for hospitals and health systems worldwide. Based on a recent report, there has been an increase in rates of hospital-acquired sepsis (HAS), or sepsis “not-present-on-admission”, in California from 2020 to 2021. Aspiration pneumonia was identified at our health system as an independent risk factor for in-hospital mortality in sepsis patients. Understanding the occurrence of aspiration in the sepsis diagnosis timeline could provide opportunities to intervene and improve patient outcomes; therefore, our goal was to explore the timing of aspiration among patients with HAS.

Methods: We conducted a retrospective chart review of all patients with ICD-10 codes for sepsis “not present on admission” and aspiration pneumonia who were discharged from our academic medical center July 2022-February 2023. The onset of HAS was based on the time at which a patient had a severe sepsis best practice alert (≥2 SIRS criteria + organ dysfunction) in the electronic health record (Epic, Inc). Aspiration timing was determined by date and time of radiology report readings or, if missing, by date and time the event was documented in the progress notes. Details of the aspiration collected included whether it was associated with intubation, a level of care change, and whether a patient was on aspiration precautions at the time of the event. Time from aspiration to severe sepsis alert was calculated and compared using descriptive statistics.

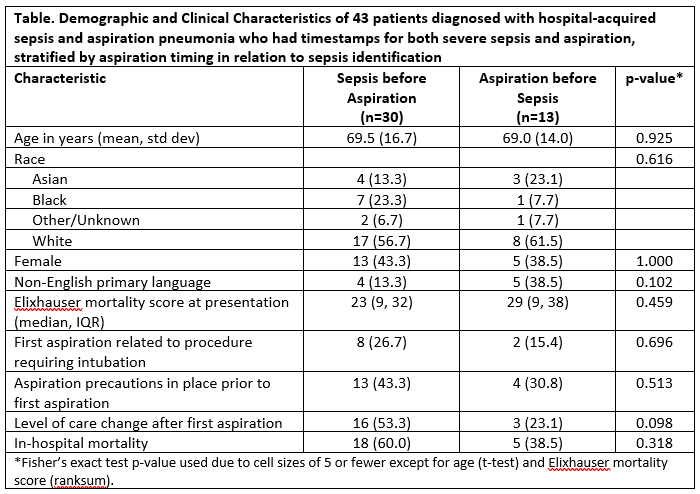

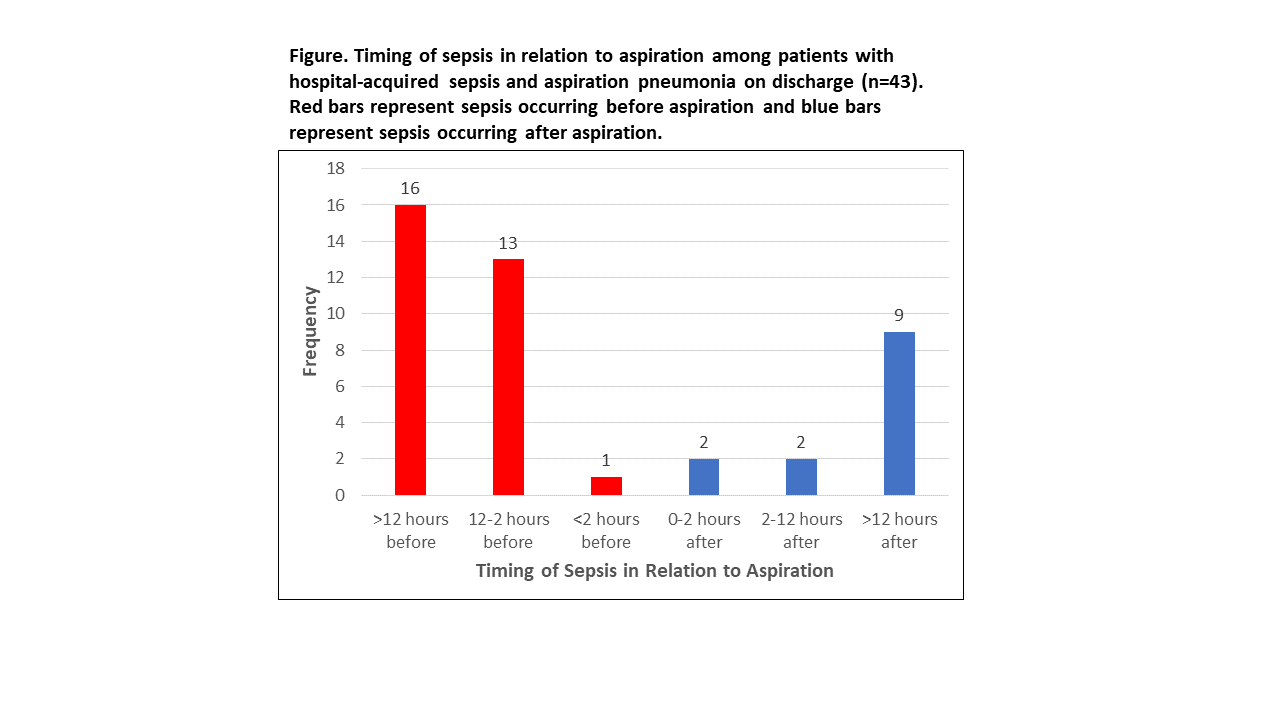

Results: There were 399 patients identified with HAS during the study period, with 64 experiencing confirmed aspiration pneumonia/aspiration pneumonitis (16%) based on chart review. A total of 43/64 (67%) had both a severe sepsis alert timestamp and aspiration timestamp. Most patients with both timestamps had a severe sepsis alert prior to documented aspiration (n=30, 70%), a median of 19 hours before aspiration (IQR 93-5 hours before) (Figure). There were no significant differences in demographics between groups (Table). Only 17/43 patients were on aspiration precautions at the time of aspiration (40%) and there was no statistically significant difference in precaution use based on timing of aspiration (43% in sepsis first, 31% in aspiration first, p=0.513). No statistically significant difference in level of care change after first aspiration was identified between groups (53% in sepsis first, 23% in aspiration first, p=0.098). There was also no statistically significant increased risk of in-hospital mortality based on timing of sepsis and aspiration in this cohort (60% in sepsis first, 39% in aspiration first, p=0.318).

Conclusions: Our study revealed that, among patients with both HAS and aspiration pneumonia on hospital discharge, severe sepsis was recognized prior to first aspiration in most cases, suggesting that aspiration may not have been the root cause of sepsis in our study population. Conversely, sepsis could predispose patients to aspiration. Future research should be conducted to determine whether sepsis is an independent risk factor for aspiration and whether institution of aspiration precautions in those at greatest risk would improve patient outcomes.