Case Presentation: A 12 year-old girl with a history of asthma and migraine headaches presented to the ED with a one week history of headaches and bloody tears. She first developed headache and left eye pain and pruritis one week prior, followed by blurry vision and bloody discharge from the left eye. She presented to an outside ED and was discharged with no specific treatment. After returning to the outside ED with no improvement, she was referred to an ophthalmologist. MRI of the brain and orbits was obtained, which noted normal appearance of the orbits and brain, but left maxillary sinusitis with a notable fluid level. She was prescribed topical ophthalmologic solution, oral antibiotics, and oral corticosteroids. She was seen the next day by another ophthalmologist with reported normal exam other than hemolacria. She was told to continue treatment. The day prior to admission, she experienced visual loss of the left eye, prompting a visit to our ED. On exam, other than mild tachycardia at 93 bpm, vital signs were unremarkable. Her exam was unremarkable other than her left eye, found to have bloody discharge (Figure 1); intact extraocular movements; equal, round, and reactive pupils bilaterally, with no conjunctival injection. Left eye visual acuity was noted to be 20/200, but was thought to be due to bloody discharge. She was admitted and started on intravenous ampicillin/sulbactam after review of outside hospital MRI confirmed left maxillary sinusitis. Consultation with ophthalmology and head and neck surgery confirmed diagnosis and treatment. Her hemolacria rapidly resolved, and she was discharged on oral amoxicillin clavulanate and intranasal fluticasone.

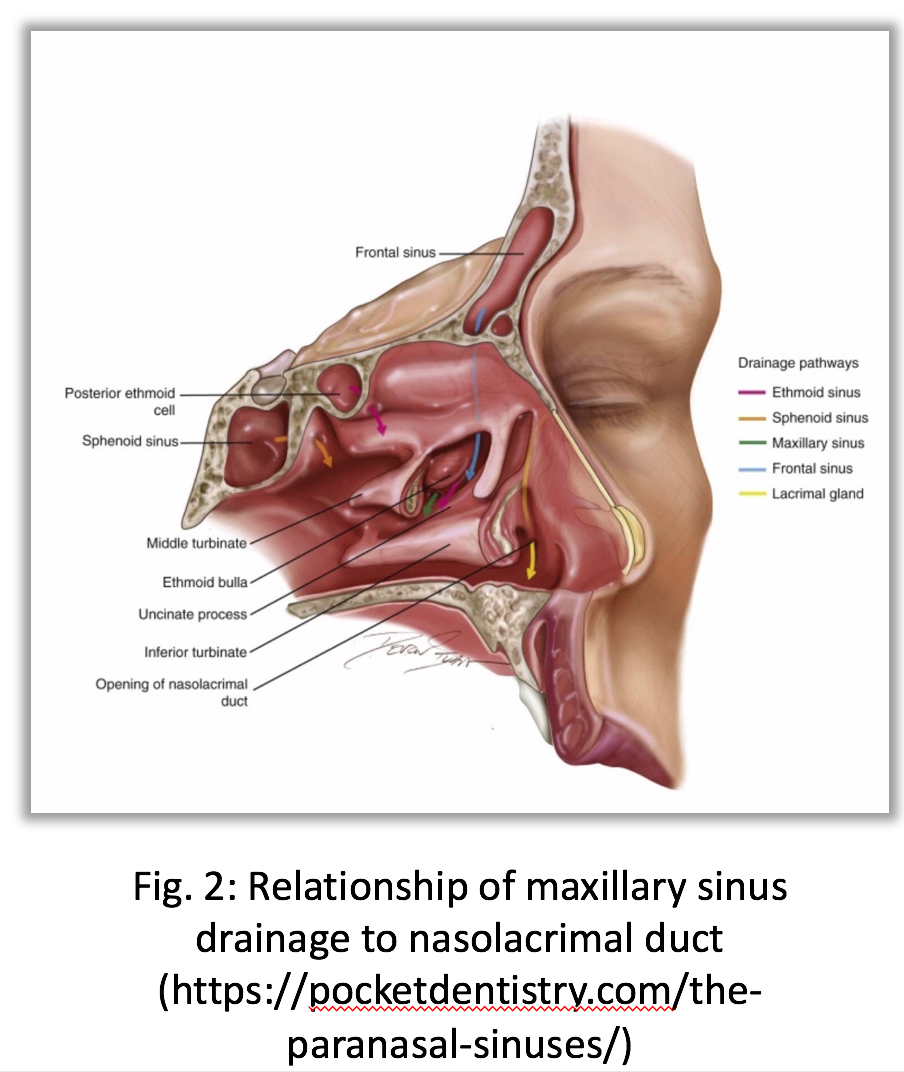

Discussion: Hemolacria, or blood present in tears, is a rare presenting sign, and even more rare in the pediatric population. Underlying etiologies can include capillary hemangioma, telangiectasia, trauma, retrograde epistaxis, conjunctivitis, and nasal or paranasal neoplasms. Rarely, patients can be afflicted by intermittent hemolacria with no clear etiology after extensive workup. Hemolacria can also be seen after prior head and neck surgery, including Le Fort osteotomy, orbital floor fracture repair, and retinal surgery. Underlying bleeding diatheses have been described when associated with other bleeding and/or bruising. Bloody drainage from the sinuses can enter the nasolacrimal duct due to its proximity (Figure 2),, leading to hemolacria, as in the case of our patient.

Conclusions: Hemolacria is an extremely rare and sometimes troubling sign in children, and should prompt an immediate workup for underlying etiologies. This may require imaging, endoscopy, consultation with ophthalmology and/or head and neck surgery. Treatment of underlying infectious sinusitis can lead to prompt resolution of hemolacria.