Case Presentation: A 75-year-old male with a medical history significant for a distant myocardial infarction, hypertension and type 2 diabetes presented after two episodes of sudden loss of consciousness without prodrome. His echocardiogram showed a normal ejection fraction (EF) and telemetry was unremarkable. He was discharged with a wearable patch for continuous ECG monitoring. After a third syncopal event carotid massage was performed, causing the patient to feel dizzy and then go into a sustained ventricular tachycardia (VT) followed by a 5 second pause. He was anxious and had palpitations but remained hemodynamically stable and did not lose consciousness. The VT resolved without intervention. The ECG monitoring patch was mailed in for interrogation.

The patient’s home dose of metoprolol was held in anticipation of an electrophysiology study and he began to have frequent runs of VT. An ECG captured monomorphic VT that appeared to originate from the posterior left ventricle. Cardiac MRI showed a scar in the left ventricle. Left heart catheterization (LHC) showed triple vessel disease. Placement of an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) was prioritized with plans for later revascularization and ablation.

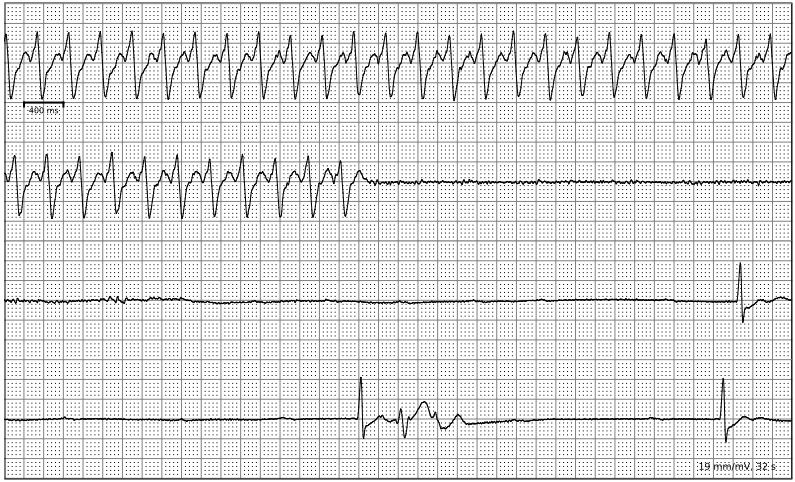

The ECG patch analysis later showed several prolonged episodes of VT, including one that corresponded with his third episode of syncope. It also showed several apparently asymptomatic pauses of 5 seconds or longer (the longest being 12 seconds), usually during the recovery period from VT.

Discussion: While ventricular tachycardia causing syncope in a patient with ischemic heart disease may not be a rare diagnosis, this case highlights the importance of a correct diagnosis. Patients with a cardiac cause of syncope have a higher mortality than those with a non-cardiac cause. Features that predict a cardiac cause include a history of heart disease, ECG abnormalities and the absence of autonomic prodrome. In patients with ischemic heart disease VT is a leading cause of both syncope and sudden cardiac arrest and must be ruled out, either with inpatient telemetry or outpatient ECG monitoring. ICDs are recommended for patients with ischemic heart disease who experience stable or unstable VT. Evaluation for ischemic disease and revascularization is also recommended, however it is unclear if revascularization benefits patients with normal EFs or affects the incidence of VT.

Conclusions: This case highlights the challenges and potential pitfalls in isolating a diagnosis in cases of cardiac syncope. The broad differential made this a great learning case. The story was immediately concerning for cardiac syncope but a normal ECG and EF were falsely reassuring. The patient met criteria for carotid sinus hypersensitivity (3 or more seconds of asytole after carotid sinus massage) but it was not clinically significant. Discontinuing metoprolol revealed the patient’s burden of VT, making that the more likely culprit. Finally, it seemed like the VT was coming from a small area of scar given the patient’s normal EF, but cardiac MRI and LHC exposed severe ischemic heart disease.