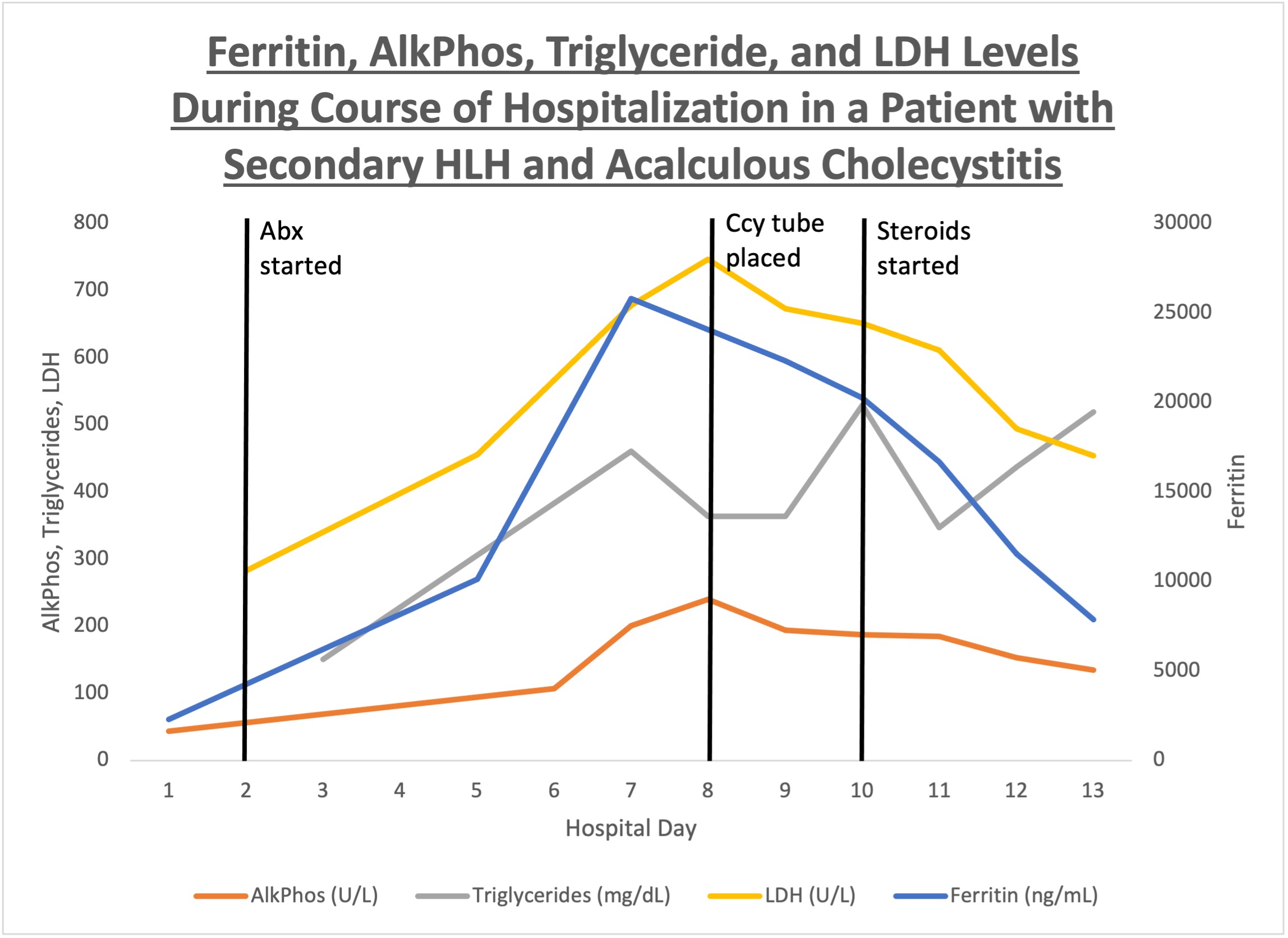

Case Presentation: A 23-year-old male with granulomatosis with polyangiitis with renal involvement (on azathioprine), stage 4 chronic kidney disease (baseline renal function) presented with fever, weight loss, and new pancytopenia. Broad-spectrum antibiotics were started and a comprehensive infectious work-up was done, including bacterial cultures, viral tests, and fungal serologies. Initial imaging was unremarkable for any source of infection. Bone marrow biopsy showed a hypocellular marrow with no evidence of malignancy or hemophagocytosis. Despite aggressive management of sepsis, patient continued to decline clinically and developed abdominal pain and elevated liver function tests. Repeat abdominal imaging showed an edematous gallbladder wall concerning for acute acalculous cholecystitis and splenomegaly. HLH was suspected when patient was found to meet the clinical criteria. This included fever, splenomegaly, cytopenia, hypertriglyceridemia, elevated liver function tests, hypofibrinogenemia, elevated ferritin, absent NK cell activity and elevated soluble CD25 receptor levels. Dexamethasone (10 mg/m2 daily for 2 weeks with taper) was started. Within 24-48 hours, fever resolved, and inflammatory markers started trending down. Genetic testing for primary HLH was negative.

Discussion: Acquired HLH can occur in patients with autoimmune diseases on iatrogenic immunosuppression with or without the presence of infection. Our patient with Granulomatosis polyangiitis was in remission for the last three years but remained on immunosuppressive therapy making him high risk for developing HLH. Both sepsis and HLH have several overlapping features [1]. It is important for the patient to undergo a comprehensive infectious work-up. It is unclear if acute cholecystitis was a potential trigger for developing HLH, or intense immune activation and cytokine storm of HLH caused gallbladder inflammation. Since our patient did not respond to antibiotics, we suspect that inflammatory response activated in the body from HLH caused this cholecystitis. Elevated liver enzymes with abdominal symptoms should be a sign of gallbladder inflammation in patients who are meeting HLH criteria. If acute cholecystitis is thought to be a potential trigger of HLH, antibiotics should be started and tapered based on cultures. However, early initiation of immunosuppressive therapy under careful observation can reduce mortality and can ultimately control the activated immune/ cytokine pathway and improve gallbladder inflammation [2,3]. This is also superior to early surgical intervention including drain placement and cholecystectomy.

Conclusions: HLH and sepsis have several overlapping features, therefore comprehensive infectious work up is recommended. Abdominal pain with or without elevated liver function tests should raise suspicion of acalculous cholecystitis in patients with HLH. Starting the steroids as per HLH protocol should be prioritized and will be lifesaving.