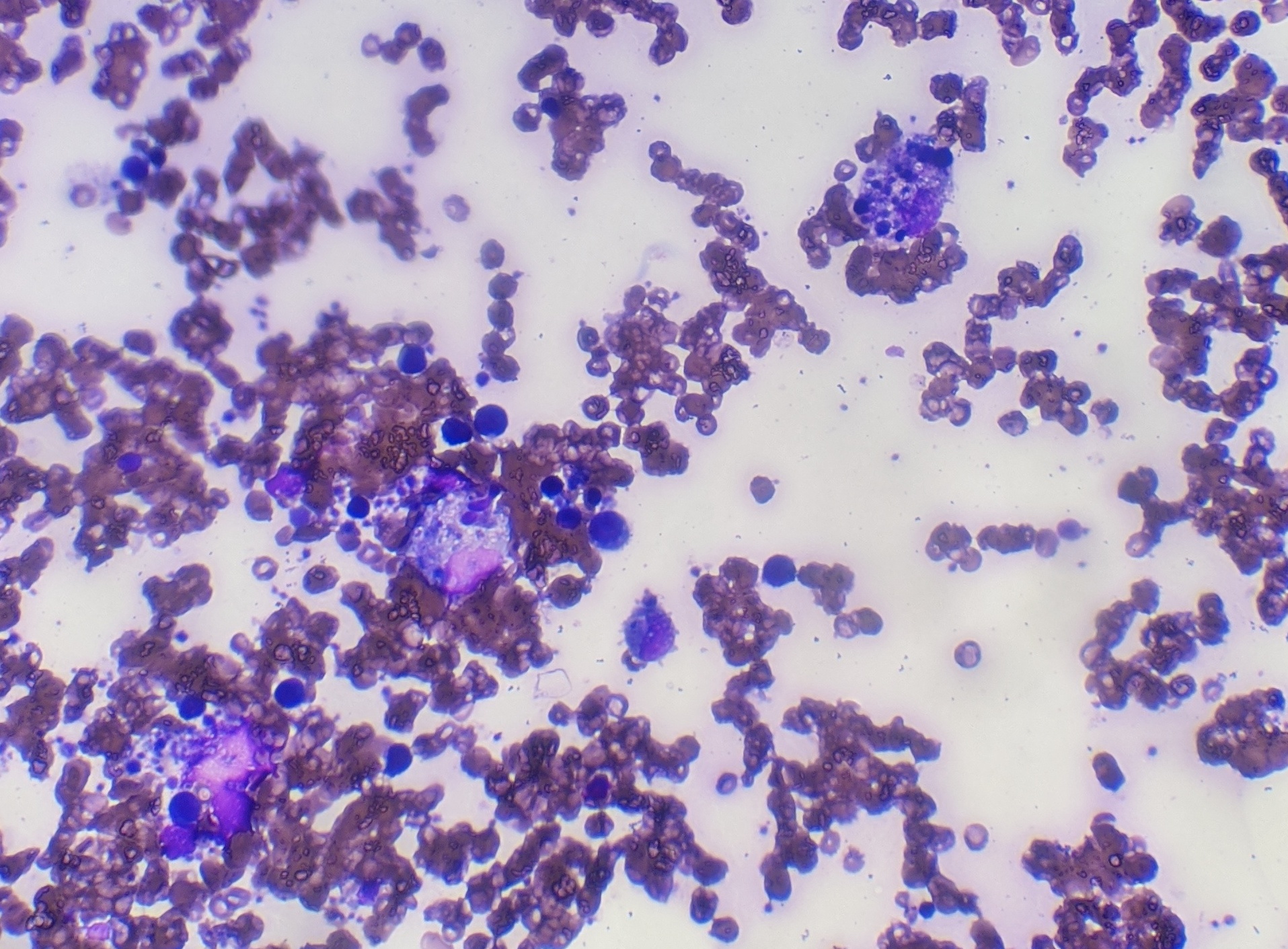

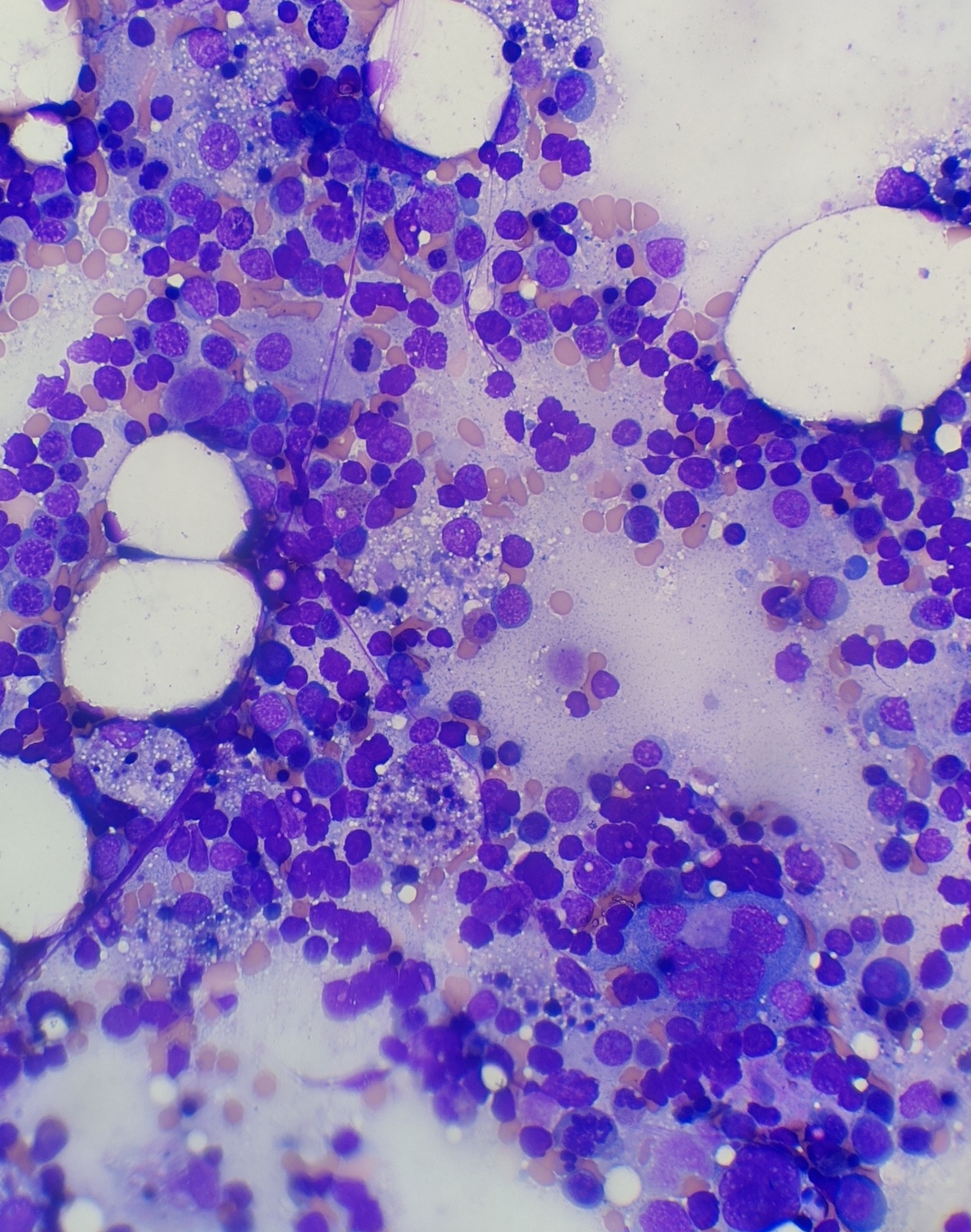

Case Presentation: A 25-year-old African American female with a history of SLE and seizure disorder presented with generalized weakness, fever, odynophagia and loss of appetite for one day. At presentation her vital signs were T 101.5 °F, HR 126/min, BP of 90/56 and O2Sat 99% on room air. Initial laboratory results revealed WBC of 7.7 K/ul, Hgb 11.5 gm/dl, platelet of 146 × 109/L and band neutrophil of 63 %. Furthermore, creatinine of 2.5 mg/dl, BUN 60 mg/dl, calcium 6.5 mg/dl, bicarbonate 16.1 mEq/L, anion gap 16, albumin 3.1 g/dl, AST 1029 IU/L, ALT 254 IU/L, ALP 183 IU/L, total bilirubin 0.8 mg/dl and COVID 19 nasal PCR was negative. She was admitted with initial impression of sepsis and started on broad spectrum antibiotics. She then became less interactive, more fatigued and spiked daily fevers ranging from 101-103 °F with a pulse rate of 110. Her Hgb dropped by 3.5 gm/dl within 2 days, requiring 2 units of pRBC and 2 units of cryoprecipitate. Additional lab work revealed ferritin of 52645 ng/ml, INR 1.7, fibrinogen 90 mg/dl, haptoglobin 210 mg/dl, LDH > 3600 IU/L, blood culture, urine culture, fungal culture, CMV, EBV, Adenovirus, hepatitis panel were all negative. CT scan without contrast of abdomen/pelvis and chest was unremarkable for any infectious etiology. She remained febrile and tachycardic continuously for five days. Further work up including C3 74 mg/dl, C4 14 mg/dl, dsDNA 7, HIV, and anti-smooth muscle antibody was non-diagnostic. MRI brain was not suggestive of cerebral lupus and lumbar puncture was deferred as the patient was extremely fatigued. Given low suspicion of infection and a possible alternative diagnosis, antibiotics were weaned off and suspicion of HLH was confirmed with lab results of TG 503 mg/dl, CD25/IL 2 5697 pg/ml and bone marrow biopsy showing hemophagocytic cells (Fig 1 and 2).She was initially started on solumedrol of 40 mg Q8 H and later changed to dexamethasone 10 mg per day. Over the next 48 hours her mental status markedly improved, fever subsided, and tachycardia resolved. All inflammatory markers trended down and over the period of one week she was discharged with tapering steroids.

Discussion: HLH is a syndrome characterized by dysregulated activation and proliferation of lymphocytes with massive cytokine release, resulting in a sepsis-like syndrome with multiorgan failure. Primary HLH is a rare inherited disease in childhood, whereas secondary HLH can be induced by infections or malignancies. Diagnosis of secondary HLH is particularly challenging, as the syndrome can be induced by severe infections, autoimmune disease or malignancy and requires extensive work up like our patient underwent. The features of HLH may include fever, cytopenia, abnormal liver tests, DIC, delirium, marked elevated inflammatory markers and multiorgan involvement. Given the broad range of systemic symptoms HLH can often mimic other systemic disorders and create a challenge when differentiating from etiologies like cerebral lupus, as was the dilemma in our case. Different diagnostic criteria exist to make the diagnosis including soluble CD25 and bone marrow biopsy revealing hemophagocytic cells, however these cells are not pathognomonic. Treatment strategies include steroids, chemotherapy and immunotherapy.

Conclusions: HLH should be suspected in patients with underlying autoimmune disease presenting with an inflammatory response and multiorgan involvement. Early recognition is important because mortality rate of adult patients diagnosed with HLH exceeds 50%. Steroids can be used as first line treatment.