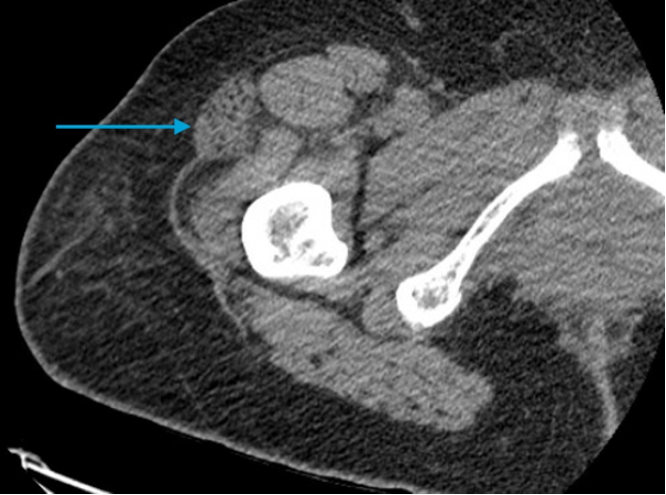

Case Presentation: A 60-year-old female with no past medical history presented to the emergency department with subacute worsening right thigh swelling and pain. Her history included mild trauma to her right thigh during a recent cross-country road trip. Her physical exam showed significant swelling and tenderness to the anteromedial right thigh with palpable distal pulses and no warmth, redness, discoloration, or tightness. Right lower extremity strength was 3/5, with limited range of motion due to pain. On admission, she was hemodynamically stable and afebrile. Pertinent labs revealed mild leukocytosis, glucose of 345 mg/dL, creatine phosphokinase (CPK) of 691 units/L, and hemoglobin A1C of 14.0. Imaging revealed a non-occlusive filling defect of the proximal right external iliac artery resulting in initiation of therapeutic enoxaparin. Despite initial clinical improvement, she continued to exercise vigorously in her hospital room. Her symptoms acutely worsened prior to discharge. A repeat CT of her femur was ordered to rule out hematoma in the setting of anticoagulation. Results demonstrated hypoattenuation and enlargement of the vastus lateralis muscle with fasciculation loss, confirming the diagnosis of diabetic myonecrosis (DMN). After being advised to rest, she was discharged to recuperative care with follow-up at a diabetes education clinic.

Discussion: Though exact pathogenesis is unclear, vasculopathic changes associated with long-standing diabetes may play a role in DMN. Many present with normal laboratory findings, but patients can exhibit mildly elevated CPK levels or leukocytosis. Concordance between clinical symptoms and radiologic findings are diagnostic. Although an MRI is usually preferred, a CT was diagnostic in this patient, as we were ruling out hematoma. Most patients with DMN have coexisting diabetes complications, with nephropathy present in 75% and retinopathy in 47%. In contrast, our patient lacked any prior DM diagnosis or its expected secondary manifestations. Also notable is the history of acute trauma to the affected area, which skewed our initial suspicions and led to an unconventional path to diagnosis. Though her history of prolonged immobilization suggested DVT, the workup was revealing only of an incidental non-occlusive thrombus that insufficiently explained her symptoms. The inciting trauma event was also suggestive of a hematoma or rhabdomyolysis, but the CPK level was far below the expected value for the latter, and the urinalysis results suggested true hematuria rather than myoglobinuria. Treatment of DMN usually involves symptomatic management with rest, optimal glycemic control, and low-dose aspirin. Aspirin use was avoided in our patient, as she was already prescribed blood-thinning agents. Notably, physiotherapy during the first few weeks is not recommended, as it has been shown to worsen conditions and prolong time to resolution. Our patient’s acute worsening after exercising supports these findings. For such patients without established DM diagnosis, a high index of suspicion is necessary to avoid exacerbation by exercise or unnecessary antibiotic/anticoagulant use, as conservative management typically leads to symptomatic resolution.

Conclusions: We present an uncommon presentation of diabetic myonecrosis (DMN), a rare complication of long-standing, poorly controlled diabetes mellitus. For such patients with misleading history of trauma, lack of diagnosed diabetes, or DVT risk factors, early suspicion for DMN is crucial for treatment.